_ RCGP Learning

User blog: _ RCGP Learning

No-one expects their child to die before them – it isn’t the natural order of things.

From miscarriages to stillbirths and from perinatal deaths to deaths in childhood, the death of a child is a unique type of loss.

Pregnancy loss is the most common form of child loss. It is currently estimated that one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage1 so it is something many parents will experience. Even though they may have never been able to get to know their child, they will still feel a huge loss. They grieve the potential to get to know that child and the life they would have had. Many parents will also feel a sense of guilt following a miscarriage so it is important to look out for any hint of this and to reassure the parent that this was not their fault.

When a parent loses a child of any age, in that split second, their world is changed forever. They lose not only their child, but also many of the social networks linked to their child. They lose the potential to see that child grow up and if the child was their only child, their identity as a parent and the chance to become a grandparent. They lose not only the present but also the future. The loss of a child for this reason is very different to other types of grief.

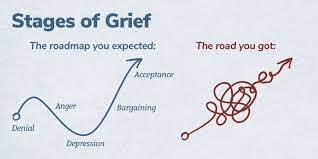

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

In 2007, Harper et al showed that in the 15 years after losing a child or having a stillbirth, bereaved mothers were 2-4 times more likely to die than non-bereaved mothers and that the excess risk persists for 35 years after the bereavement, though the magnitude of the risk drops with time. The increased risk persists for three years for fathers, though clearly they have an increased risk of being widowed for much longer. The reasons for this phenomenon are not clear, but could involve immunosuppression due to severe stress, maladaptive coping strategies such as alcohol misuse, pre-existing poor health which may have contributed to the child bereavement, mental ill-health following bereavement, or bereaved parents presenting later with their own physical health problems. Further research into this area would be useful. The relevance to general practice is probably that we should be aware of this risk and make particular use of the GP ‘spidey sense’ when dealing with this group of patients. Never ignore your gut feeling as a GP – it has been shown to be reliable3.

I am writing this blog from personal experience, after losing my four-year-old daughter Grace to cancer in 2014. My personal experiences have helped me to support many other families in similar situations and in 2018 I wrote an eLearning course for the RCGP, designed to provide GPs with the tools to support patients who have experienced a loss during pregnancy, or the death of an infant or child. Each family needs something different, but the overwhelming message is that having someone simply able to be there for them as a point of contact, it can make a big difference.

When a family loses a child, it also has a significant impact on their siblings. Life for their surviving siblings never returns to normal so it is important to remember that their bereavement will affect many aspects of their life and behaviour.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

Often, a few simple measures taken by a practice can make a sizable difference to help families realise that they are not alone. When the practice has been informed of a child death, it is important to contact the family, by phone if possible. This need only be brief, but families do appreciate this and remember this contact down the line.

Families should be provided with a named GP, and alerts placed on the notes of both parents and all siblings so practice staff and professionals can be aware of the history without the family needing to repeat themselves each time.

If possible, enable bereaved parents and siblings to make appointments at minimal notice for a limited time. The death of a child can plunge a family into chaos meaning things are easily forgotten or they may need to be seen quickly to help with acute emotional situations.

Ensure that all professionals are notified. Check that electronic alerts inviting the deceased child for immunisations, reviews or other routine care have been turned off. It is also useful to familiarise yourself with the services and support that are available in your local area to signpost families to as required.

General Practice is extremely busy at the moment, but these simple measures are relatively time efficient and can make a real difference to these families.

References

1 Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O'Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med, 1988; 319(4): 189-94.

2 Harper M, O'Connor RC, O'Carroll RE. Increased mortality in parents bereaved in the first year of their child's life. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2011; 1(3): 306-9.

3 Friedemann Smith C, Drew S, Ziebland S et al. Understanding the role of GPs’ gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. British Journal of General Practice 2020; 70 (698): e612-e621.

'Stages of Grief' image used with permission from WPSU's Speaking Grief project.

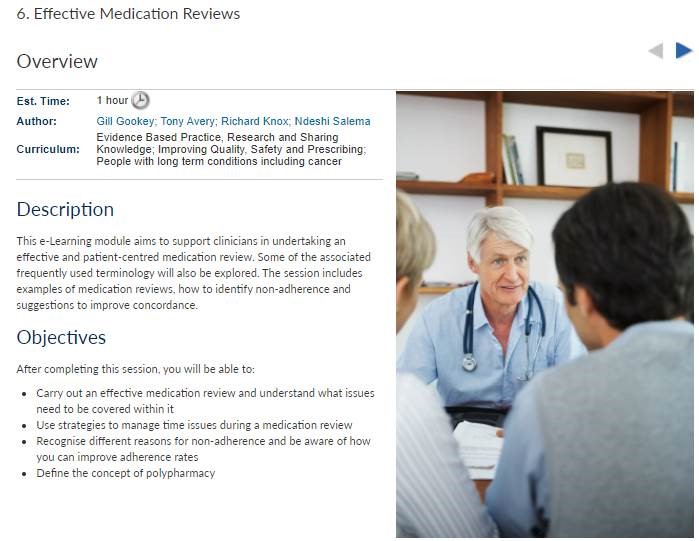

An NIHR GM PSTRC (NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre) funded free e-learning course which has been accessed by 7000 prescribers since 2014 has undergone an evaluation and been re-launched with the addition of new content.

Dr Richard Knox from the University of Nottingham is one of the researchers who has worked on the e-learning course, Prescribing in General Practice. He talks about the impact of the course and the new updates here:

Prescribing in General Practice is an e-learning course, hosted on the Royal College of General Practitioners’ (RCGP’s) e-learning platform. It’s a case-based approach designed by prescribers so there’s a focus on real life examples. It was launched in 2014 and has recently undergone revisions from people who use it to ensure all the real-life examples that are used meet current guidelines. The course was also evaluated by researchers at the GM PSTRC in a new paper, which has been published in the journal Education for Primary Care.

To help assess the course’s success, in the paper, researchers used the results of a questionnaire completed by those who finished the e-learning modules. According to this the course had a positive impact on knowledge, skills and attitudes. More than 98% of 750 survey responders said the course had been a useful part of their continuing professional development.

Those who responded also wrote additional feedback and some examples are below:

“This module comprehensively covered contemporary prescribing issues particularly with respect to safety. It was grounded in everyday practice and informed by real life examples of prescribing errors and how they may occur and how to mitigate against them at an individual and at a systems level.”

“Usefully it was from the RCGP so the majority of medicines and cases presented were similar to what I would encounter on a daily basis in work. I feel from completing this module my safety and efficiency in prescribing will improve.”

“This course is going to change/improve many aspects of my prescribing practice. I would definitely spend more time on writing clear instructions for patient.”

The course was initially developed to facilitate safer prescribing among GPs. However, funding from the GM PSTRC has enabled the course to be free-to-use for all prescribers, regardless of professional background. This has increased the impact of the course which improves the safety of prescribing more widely.

The original idea for the e-learning materials came as a direct result of findings from the General Medical Council’s PRACtICe study. This was a large study of prescribing errors in UK general practice, which revealed that about one in twenty prescriptions from primary care contains an error. The PRACtICe study included a root cause analysis that helped establish a set of recommended strategies that may improve prescribing. The need to invest further in education and training was identified by all GPs, whatever their stage or experience of prescribing. A series of focus groups made up of GP trainers, GPs in training, pharmacists and members of the public also confirmed support for further training to be made available. The value of e-learning was championed – with stakeholders requesting a strong case-based approach to help inform real-world practice.

The e-learning includes five distinct lessons, each taking about thirty minutes to complete:

- Lesson one – Appropriate drug selection

- Lesson two – Avoiding prescribing errors

- Lesson three – Choosing the right drug

- Lesson four – Right dose instructions

- Lesson five – Effective medication reviews

Due to the updates the course now includes specific sections on topics such as prescribing multiple medications for the same person at the same time (polypharmacy) and the use of the Seven Step medication review process.

Please note, this course is now RCGP Members' benefit. Non-members have an option to purchase the course. You can access the Prescribing in General Practice course here.

“Medicine is an art whose magic and creative ability have long been recognised as residing in the interpersonal aspects of the patient-physician relationship1”.

Art is part of medical training from early on - lectures in medical school use images, cartoons, animations, and demonstration models. In our hospital jobs we all used drawings, lung fields with crosses, or a hexagon abdomen with a large liver on it were all used in the days of paper notes. However when asked to draw, medical students often recoil and claim that they are ‘not creative’ and cannot draw2.

We are trained in communication skills to gather information in order to facilitate accurate diagnosis, counsel and give therapeutic instructions whilst establishing caring relationships with patients3. Patients gather information from many different visual sources in the GP surgery, so using drawings is a natural next step, yet one that is rarely discussed.

We already use visual imagery in the consultation - as GPs we might point to anatomical posters in our rooms, use drawings for minor surgery consent, or the “clock test” in dementia screening. Encouraging people to see drawing as a form of learning can help them to present information more efficiently within the consultation4.

We also all use metaphor and analogy frequently - as Anatole Broyard describes, metaphors may be as necessary to illness as they are to literature and are a relief from medical terminology5. Metaphors bridge the communication gap between healthcare professionals and patients, examples including the following:

“My tongue feels weird, like licking a battery.” (Oral thrush)

“Doctor, you know when you put your hand in a bag of rice – that nice sort of tingly feeling – I get that in my head in a sort of shock.” (SSRI discontinuation syndrome)

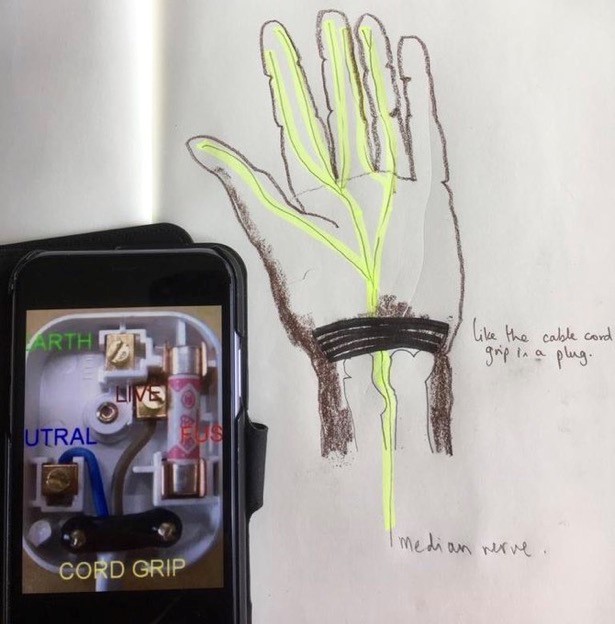

Clinicians can use visual metaphors; drawing a plug to describe the wrist retinaculum (Image 1) can increase understanding of the pathophysiology of carpal tunnel symptoms and be a simple start from which patients can improve their understanding.

Clinicians can use visual metaphors; drawing a plug to describe the wrist retinaculum (Image 1) can increase understanding of the pathophysiology of carpal tunnel symptoms and be a simple start from which patients can improve their understanding.

While anecdotal evidence for the benefits of drawing in the consultation is plentiful, research is limited: A team at Edinburgh university were the first to document the use of drawing amongst 100 surgeons, 92% of whom valued drawing in surgical practice2. Similarly, the vast majority of patients valued drawing in moderate or complex surgery consent explanations3. There is plenty of evidence for the neurological and cognitive benefits of using images in undergraduate and postgraduate pedagogy4, alongside the cognitive processing of learning5.

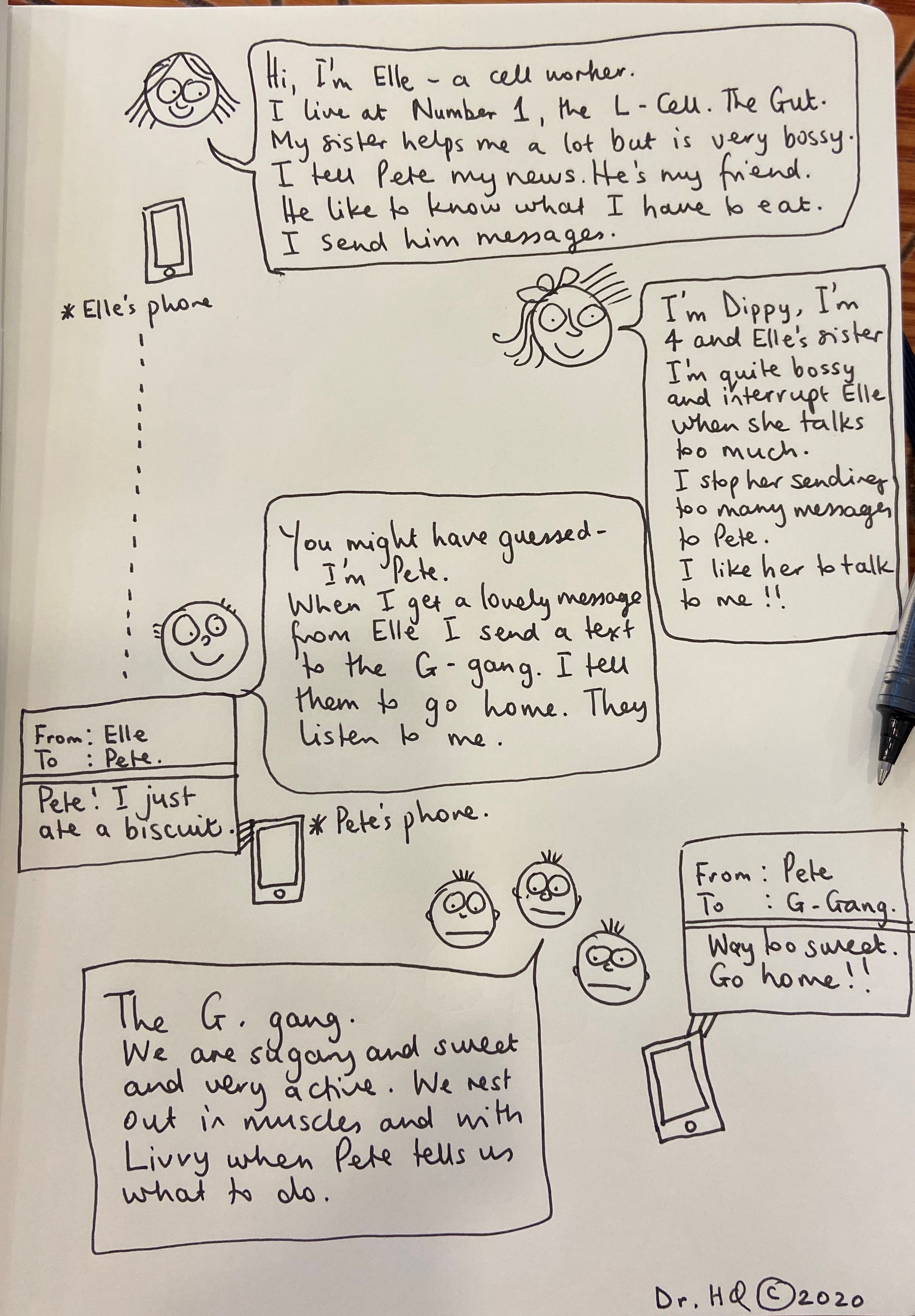

Before I studied medicine I attended the Glasgow School Of Art, reading Visual Communication. I was taught to consider what it was I wanted to say, and then work out how best to communicate it visually. This meant considering which material to use and to capture the spirit of the subject I was drawing using appropriately descriptive markings. This trained me to describe the essence of a concept or object and its function or position in the world. These principles can add value to a consultation as drawing supplements or contextualises the words we use. It can improve a patient’s understanding of physiology, pathology and pharmacology and reduce health anxiety; there is evidence that patient drawings can predict health outcomes and provide doctors with more insight into the patient experience6. Cartoons can be particularly helpful to explain pharmacology, particularly for those with limited literacy (Image 2). Colour is important – the red of an inflamed tympanic membrane, or a different colour to demonstrate a middle ear effusion. Just a few different pens can improve understanding.

My patients often ask to keep the drawings that I do (sometimes with the patient’s help) in a consultation as it represents their understanding of what was said. I see drawing as an adjunct in communication and possibly as a way to reduce complaints that can arise when patients feel that they have not been heard.

The use of images is not one-way as patients may add their own drawing, or bring pictures on their mobile device6. The following drawings (with patient permission) show personal representation of the pain experience in cluster headache (Image 3) and in these descriptive sketches (Image 4) the pain of end stage osteoarthritis with spondylolisthesis. Reference to the feeling of dragging and vice-like pain can be seen. I am not alone – there are other professionals using imagery in medicine.

Professor Gabrielle Finn fosters a network of artists, scientists, educators and health professionals interested in alternative methods of displaying by painting anatomical structures directly onto the body. Her work can be found at paintmeanatomy.com, and she has kindly given permission for an image to be used here (Image 5). Her work crosses specialties and encourages innovative alternative approaches to learning.

The team around Professor Paul Rea, Professor of Digital and Anatomical Education at the University of Glasgow, created an animation explaining hypertension using clay models which simply describe concepts which are difficult to describe verbally.

Professor Alice Roberts, Professor of the Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham, uploads anatomical videos of embryological folding, and musculoskeletal anatomy, sometimes with the help of Jelly Babies.

In summary, at times there is a need in the doctor-patient consultation to change or extend the communication style. We can let our patients take over the pen to illustrate their concerns or symptoms. Good communication within the GP consultation and the use of alternative techniques to describe issues are valuable tools : sometime words fall short.

This blog was written by Dr Holly Quinton, GP and Illustrator. All images in this blog were provided by Holly with patients' consent. You can read more about Holly and visual consultations in the following BJGP article: How I use drawing and creative processes within the GP consultation.

References:

1Hall JA, Roter DL, Rand CSJ Health Soc Behav. 1981 Mar; 22(1):18-30

2Keenan I, Hutchinson J, Bell K, 2017, 'Twelve tips for implementing artistic learning approaches in anatomy education', MedEdPublish, 6, [2], 44, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000106

3 Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R, Buffone N, Lofton S, Wallace M, Goode L, Langdon L; Participants in the American Academy on Physician and Patient's Conference on Education and Evaluation of Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004 Jun;79(6):495-507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. PMID: 15165967.

4 Keenan I, Hutchinson J, Bell K, 2017, 'Twelve tips for implementing artistic learning approaches in anatomy education', MedEdPublish, 6, [2], 44, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000106

5 C Kotei: Metaphors in Medicine Synapsis Journal Oct 2017

6 Daeboudt, Broadbent, Berger & Kaptein, Lupus, 20,290-289

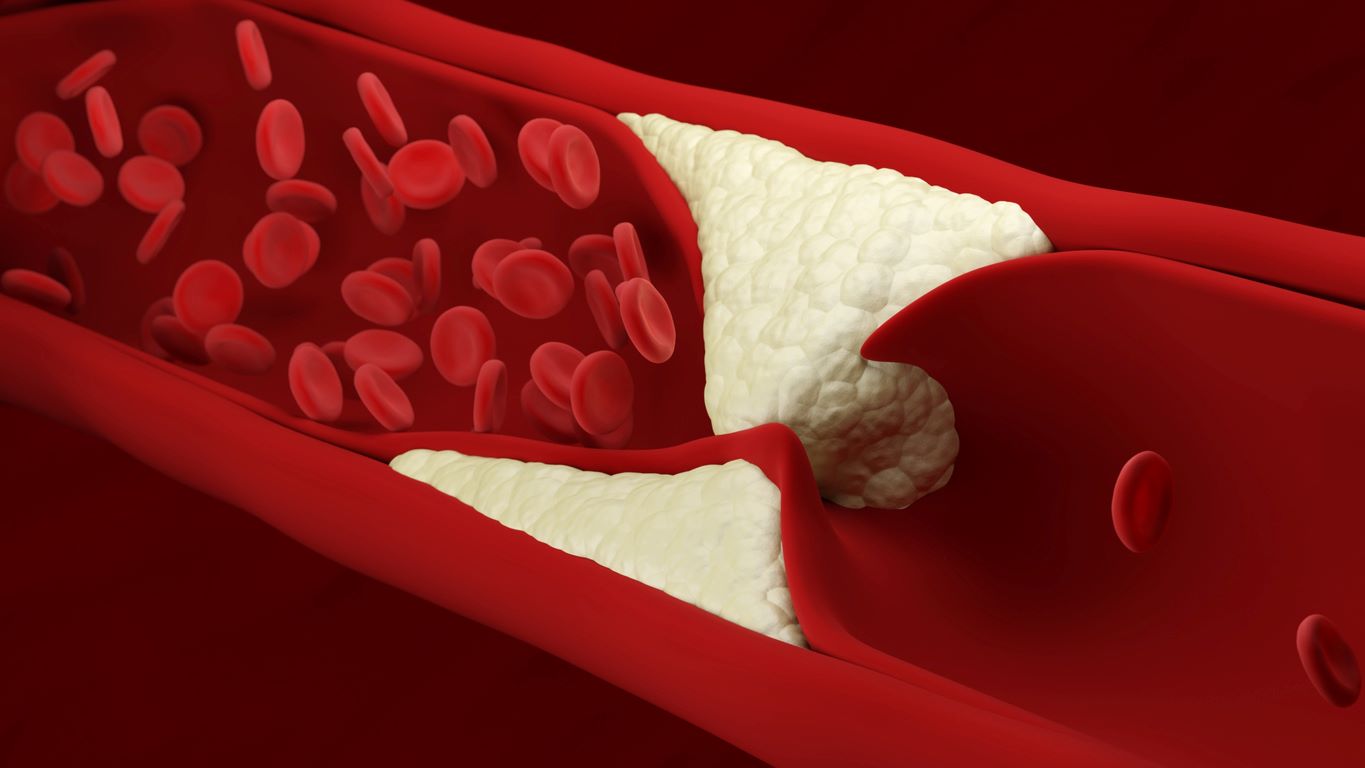

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), which comprises myocardial infarction, angina and strokes, is ranked as the number one cause of mortality and is a major cause of morbidity world wide. The current NHS long term plan contains a goal to prevent 150,000 myocardial infarctions and cerebrovascular accidents in the United Kingdom over the next few years.

For those of us working in primary care, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have for some time been an important part of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. We know that they reduce the risk of a first event for healthy individuals at high risk of CVD and reduce the chance of a further event in secondary prevention. According to NICE, statins should be offered to anyone who has a 10% or greater risk of developing CVD in the next 10 years1 which makes them one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the UK.

As the numbers needed to treat (NNT) are well within the range considered worthwhile in primary prevention (such as hypertension) but higher than in other interventions2, patients may have mixed feelings about taking continuous medication if it is not certain that they will directly benefit.

With the help of a QRISK2 calculator you can break down the numbers into a theoretical group of 100 patients all with a QRISK score of 10% and demonstrate the numeric benefit.

On a population level, the benefits of taking statins are a lot more evident. According to NHS England, if only 45% of the people in the ‘at high risk’ category for CVD were identified and treated, 6000 strokes and heart attacks could be avoided over the next 10 years3. NICE estimate that when treating 500 people over a period of 3.9 years, 1 death from CVD could be avoided. They also estimate that treating 46 people for 3.7 years would prevent one non-fatal myocardial infarction4. From a public health point of view, this would prevent a significant amount of events and deaths overall considering there are 7-8 million people taking statins in the UK alone5.

Patients may be reluctant to start or continue taking statins if they hear negative media reports about their side effects. A study from the British Heart Foundation (BNF) found that 11% of people were more likely to stop taking statins for primary prevention of CVD, after a period of particularly negative media coverage during 2013-20145.

Patients may be reluctant to start or continue taking statins if they hear negative media reports about their side effects. A study from the British Heart Foundation (BNF) found that 11% of people were more likely to stop taking statins for primary prevention of CVD, after a period of particularly negative media coverage during 2013-20145.

NHS England are currently reviewing if high-dose statins can be made available directly from pharmacists, to enable easier patient access and ultimately lower the levels of heart disease and stroke. They estimate that these conditions cost the NHS more than £7 billion a year3, whereas dispensing statins costs around £98 million a year as of 20185.

The following resources can help with explaining the benefits and risks of statins to patients:

- British Heart Foundation – Statins information sheet

- NICE – Are statins the best choice for me?

- NICE – Patient decision aid

- PHE - Health Matters: What you need to know about statinsh

You can also access the recently launched ‘Reducing cardiovascular risk in primary care’ eLearning course for FREE on the RCGP eLearning site. RCGP Members can also benefit from access to the ‘Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease’ module in EKU 2018.1.

References

1 NICE. 2016. Are statins the best choice for me?. [Online]. Available from: http://indepth.nice.org.uk/are-statins-the-best-choice-for-me/index.html

2 Taylor, F et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (2013) Cochrane Systematic Review – Intervention https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5

3 NHS England. 2019. NHS to review making statins available direct from pharmacists as part of Long Term Plan to cut heart disease. [Online]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2019/09/nhs-to-review-making-statins-available-direct-from-pharmacists-as-part-of-long-term-plan-to-cut-heart-disease/

4 NICE. 2016. Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (NG56). [Online]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56/resources

5 British Heart Foundation. 2020. Statins: 10 facts you might not know. [Online]. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/for-professionals/healthcare-professionals/blog/statins-10-facts-you-might-not-know

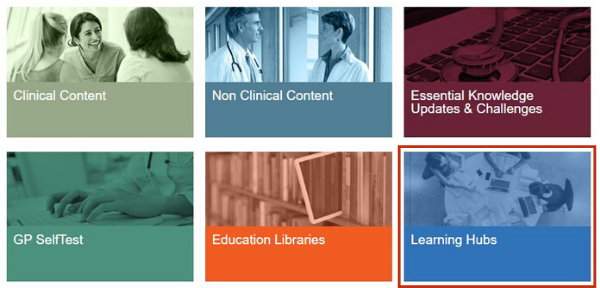

The Learning hubs are the newest addition to the RCGP’s Online Learning Environment (OLE) and serve as a ‘one-stop shop’ for any resources that GPs may need to find on a specific topic. Within each hub, there are various modes of learning, including standard eLearning courses and bite-sized learning such as; screencasts, podcasts, apps and patient journeys.

The link to the main hub page is conveniently located on OLE homepage, in a blue block named ‘Learning hubs’. This main page lists all of the topics available and provides easy access to each individual hub. When a user selects a hub, the hub page will show you a range of different sub-topics and the modes of learning available.

The learning hubs were introduced to provide an easy way for GPs to find the content they need for their CPD and to ultimately create a better user experience. Having a centralised topic area means that GPs don’t need to waste time searching for the content they want to access. Instead, they can find all of the resources they need in one place. GPs can dip in and out of each mode of eLearning and can therefore fit their learning around appointments and their day-to-day roles. It is also easy to track the learning they have completed on a particular topic and add this to their appraisal toolkit. Find out more about uploading RCGP eLearning completions to the Clarity appraisal toolkit.

Here are the top five benefits of using a topic-specific hub:

- As mentioned previously, GPs can spend more time learning, rather than searching for relevant CPD

- Each Learning hub features examples of the different types of eLearning you can find on the RCGP’s OLE

- Users can benefit from trying different types of learning to see which mode works best for them

- All of the learning completed in the hubs counts towards CPD

- The resources in each hub build on each other, providing GPs with a broad knowledge on that one topic

Currently, there are four hubs live on the OLE. These are as follows:

The Allergy Hub encompasses all of the types of learning available on the RCGP’s OLE. It consists of eLearning modules, an app, a podcast, a patient journey and a screencast. These resources aim to educate GPs on the various presentations of allergy, including food allergy and respiratory problems such as asthma. They also cover symptoms, management in primary care and when to refer to secondary care.

The Allergy Hub includes the following resources:

- Allergy eLearning course

- Asthma eLearning course

- Allergy education app

- Food allergy podcast

- Common Atopic Presentations in Primary Care - screencast

- Patient cases: Practical Aspects of Allergy Diagnosis – patient journey

The Autoimmunity Hub primarily focusses on coeliac disease, including an eLearning course, podcast and app that all feature this sub-topic. There is also a patient journey module which looks at four different autoimmune diseases, from initial presentation to diagnosis. These resources aim to help GPs through autoimmune disease diagnosis, management and referrals in primary care.

The Autoimmunity hub includes the following resources:

- Coeliac eLearning course

- Coeliac disease podcast

- Autoimmunity education app

- Patient cases: Managing Uncertainty in Autoimmunity – patient journey

This collection of eLearning modules, podcasts and screencasts aims to inform and update all members of the general practice team on particularly important aspects of primary care for LGBT people, to improve both experience and outcomes for our patients. It was produced with the help of a grant by the Government Equalities Office and with the guidance of the RCGP’s LGBT+ steering group.

The LGBT Health Hub includes the following resources:

eLearning courses:

- Inequality in healthcare provision: the current state of LGBT health

- Creating an inclusive primary care environment

- Mental health and suicide prevention

- Screening issues in the LGBT population

- The older LGBT Patient

- Sexual and reproductive needs of the LGBT community

Screencasts:

- Addressing LGBT Health inequalities

- Understanding the non-binary patient

- Using language that is inclusive of the LGBT population

Podcasts:

- Improving your practice to be more inclusive

- Sharing vs disclosure

- Parents of LGBT kids

The latest addition to the ‘Learning Hubs’ section is the Diabetes hub, which contains five eLearning courses, three screencasts and two webinars. Whilst the primary topic is diabetes, GPs can access a range of different topics under this umbrella; ranging from medication, lifestyle modification, the NHS Diabetes Programme and most recently, diabetes and COVID-19. These resources aim to help GPs with general diabetes management and advises on how to work with patients to control their condition.

The Diabetes hub includes the following resources:

eLearning courses:

- Polypharmacy

- Diabetes Medication Review & Optimisation

- Targeted use of Anti-Diabetics

- Type 2 diabetes and the low GI diet

- NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme

Screencasts:

- Lifestyle Modification

- Newer Insulins

- The Management of Diabetic Kidney Disease

Webinars:

- Type 2 Diabetes: Dialogue with Experts

- COVID-19 & Diabetes

Access the main hub page.

Intermittent fasting (IF) is a pattern of eating whereby the person undertakes a regular (usually daily) fast of at least 16 hours. In light of National Obesity Awareness Week in January or in keeping with New Year’s resolutions, patients may seek advice on weight loss from their GP and opinions on the efficacy of certain diets. This blog will discuss some of the evidence around fasting for weight loss and management of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and other cardiovascular risk factors.

Ingested food is stored in the body as liver glycogen and as fat, the process of lipogenesis being mediated by insulin. Energy is provided by glycogenolysis, however after around 12 hours of fasting, hepatic glycogen becomes depleted and adipose tissue lipolysis begins to occur. A recent NEJM review article suggested that ‘intermittent fasting elicits evolutionarily conserved, adaptive cellular responses that are integrated between and within organs in a manner that improves glucose regulation, increases stress resistance, and sup-presses inflammation”1

For patients, we can explain that across our evolution we not always had access to three meals a day, and that after after about 8 to 12 hours the the body enters a ‘fat burning’ phase.

There are many ways to fast, with the most basic being a fast of at least 16 continuous hours in every 24. To get results in terms of weight loss or increased health benefits, the fasts should ideally be done on a daily basis. Two popular IF methods are as follows:

- 16:8 – Fast for 16 hours and eat all meals within an 8 hour window. This typically means skipping breakfast and eating two meals a day.

- 20:4 – Fast for 20 hours and eat all meals within a 4 hour window. This would involve eating one meal or having two smaller meals a day.

A relatively short fast of 16 hours can be incorporated as part of daily life. The ‘intermittent’ nature of IF is that the fasting is flexible and at the convenience of the individual – the number of fasts per day and the exact hours of fasting can be altered if needed e.g. to allow the patient to eat normally at a social event.

Alternative methods include the 5:2 diet, which includes eating a balanced diet for 5 days out of the week and only consuming 500 calories for the remaining 2 days. Whilst this has been shown as an effective method for weight loss, it differs from intermittent fasting as it involves reducing calorie intake instead of not eating at all.

There is evidence to suggest that IF may reduce the need for prescribed insulin in patients with diabetes2.

There is evidence to suggest that IF may reduce the need for prescribed insulin in patients with diabetes2.

IF is a relatively new concept, with some studies being small and of short duration; longer and larger studies are needed. Some examples of the evidence around IF are given below:

- A 2014 crossover study of 54 patients with T2D found that the group which ate only two meals per day, had better outcomes than those who ate the same calories spread out over six smaller meals. The group eating only two meals per day had a greater reduction in BMI, waist circumference and fasting plasma glucose3.

- A 2015 literature review of 15 studies found that various types of fasting reduced weight and improved lipid profiles and called for further research, with greater information about food intake so as to differentiate between the benefits of fasting and the benefits of calorie restriction4

- A 2019 study randomised 88 obese women into four groups (control, calorie restriction and IF with or without calorie restriction). All food was measured and provided by the study. Those who fasted for 24 hours three times a week lost more weight than those who simply restricted their calories, even though the calorie intake of the two groups was identical. The fasting group also had lower lipids and fat mass than the calorie restriction group5.

- A 2019 study of 15 men who limited their food intake to nine hours in each 24 hour period, whilst wearing a continuous glucose monitor, were found to have improved glucose tolerance and fasting triglycerides during the fasting period compared to the control period6.

- Another 2019 study followed 19 participants with metabolic syndrome who limited their dietary intake to a 10 hour period for 12 weeks. There were significant reductions in BMI, waist circumference, LDL cholesterol and blood pressure7.

It seems that IF therefore has the potential to be beneficial for patients with T2D and metabolic syndrome; it may be the case that educating patients on the benefits of IF can help in the management of T2D and reduce the need for pharmacological interventions8.

IF is a relatively new concept in relation to T2D so there are no official guidelines for healthcare professionals on how to manage a diabetic patient who wishes to do try it. As with any kind of fast, it is not recommended for pregnant/breastfeeding women or for children.

RCGP members can find out more about using diet to manage Type 2 diabetes by accessing our eLearning course on ‘Type 2 diabetes and the low GI diet’. Non-members can pay £25 to access this course.

The following resources are free to both members and non-members:

- ‘Five Minutes to Change your Practice’ screencast on Updated management of type 2 diabetes in adults

- EKU Journal watch item on Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease

RCGP members can also benefit from free access to the following resources on Type 2 diabetes:

- EKU17: Diabetes in Adults, Children & Young People (Type 1 & 2)

- EKU18: Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Management

- EKU Screencast: Type 2 diabetes in adults: management

References

1 De Cabo, R., & Mattson, M. P. (2019). Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(26), 2541–2551. doi:10.1056/nejmra1905136

2 Diabetes UK, 2019. About Type 2 diabetes. [Online] Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/Type-2-diabetes

3 Kahleova H, Belinova L, Malinska H, et al. Eating two larger meals a day (breakfast and lunch) is more effective than six smaller meals in a reduced-energy regimen for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised crossover study [published correction appears in Diabetologia. 2015 Jan;58(1):205]. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1552–1560. doi:10.1007/s00125-014-3253-5

4 Grant M. Tinsley, Paul M. La Bounty, Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 73, Issue 10, October 2015, Pages 661–674,

5Hutchison A.T. et. al., 2019. Effects of Intermittent Versus Continuous Energy Intakes on Insulin Sensitivity and Metabolic Risk in Women with Overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 Jan;27(1):50-58

6Hutchison A.T., et. al., 2019. Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Glucose Tolerance in Men at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 May;27(5):724-732. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31002478

7Wilkinson M.J. et. al., 2019. Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2019 Dec 2. pii: S1550-4131(19)30611-4. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1550413119306114

8 Firmly S., et al., 2018. Therapeutic use of intermittent fasting for people with type 2 diabetes as an alternative to insulin. [Online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6194375/

Many thanks to Dr Rachel Hudson and Dr Claudia Camden-Smith for their help with producing this blog.

Stress is a problem

Being a GP can be an extremely varied and rewarding career, but the pressure of dealing with an ever-increasing number of patients every day can take its toll. It’s estimated that GPs in England alone provide first contact care to more than 1.2 million patients per day1. Many practices struggle with staffing levels, meaning that some GPs are taking on even larger list sizes than before.

Being a GP can be an extremely varied and rewarding career, but the pressure of dealing with an ever-increasing number of patients every day can take its toll. It’s estimated that GPs in England alone provide first contact care to more than 1.2 million patients per day1. Many practices struggle with staffing levels, meaning that some GPs are taking on even larger list sizes than before.

According to the Ninth National GP Worklife Survey2 of 2195 GPs, the average reported working week was 41.8 hours, which has stayed consistent since 2008. Nine out of ten GPs reported experiencing considerable or high pressure from increasing workloads, amongst other stressors such as paperwork and having insufficient time in the working day to do their jobs. The 2015 Commonwealth Fund International Survey of Primary Care Physicians found that GPs in the UK had the highest levels of stress out of the 10 nations surveyed3

A GP’s personal life can also be affected. The GMC’s 2018 report on ‘The state of medical education and practice in the UK’ found that 72% of younger GPs feel that their work-life balance has deteriorated as a result of their stress at work. The report also found that one out of four doctors had considered leaving the medical profession at least every month. One of the most alarming findings was that two out of every 100 doctors said that they had to take a leave of absence due to stress for at least one month in the last year4.

With many GPs regularly fearing that they can’t cope in their current roles, it’s not surprising that burnout is increasing. The BMA’s 2019 report on ‘Caring for the mental health of the medical workforce’ found that a total of 88% of GP partners and 85% of sessional GPs face a 'high' or 'very high' risk of burnout5. Regional reports from the RCGP found that a proportion of GPs feel so stressed that they are unable to cope. The figures for this were 31% in Wales6, 37% in Scotland7 and 32% in Northern Ireland8.

Recognising the signs of stress and burnout

Even though GPs are expected to recognise the signs in their patients, they may not always realise that they are stressed themselves. It’s easy to plough on with day-to-day tasks and to become consumed with work, so the tell-tale signs such as irritability, poor sleep and increased alcohol use may be missed. The NHS website page on stress includes lists of the physical, mental and behavioural symptoms that may be overlooked.

The NHS Practitioner Health Programme (PHP) was launched in 2008, with the addition of the NHS General Practitioner Health Service (GPH) in 2017. These services aim to provide support to practitioners who are struggling with mental health or addiction problems, so that they can find help before these issues escalate further. According to the PHP’s report on their first 10 years of service, around half of all PHP patients are GPs. Between 2008 and 2018, over 5000 doctors presented to PHP and 83.5% of these were due to mental health problems. For GPs specifically, this figure rises to 88%, with 10% presenting with addiction problems. The remaining 2% is classified as ‘other’1. In general, NHS staff have higher sickness rates than the rest of the economy. The latest sickness absence reports, from NHS digital, show that the sickness rate is now at 4.23% in England. From the sicknesses reported, 27.1% of Full Time Equivalent (FTE) days were lost due to anxiety, stress, depression or other psychiatric illnesses9.

Dealing with stress

Resilience is mentioned a lot in relation to managing stress. It can be defined as “the ability to adapt and succeed in the face of adversity and stress”. A resilient person can maintain their wellbeing and continue moving forward when they are tested by life’s difficulties. Being resilient doesn’t come naturally to everyone and can be something to develop over time. The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development have produced ‘Developing resilience: a guide for practitioners’ which contains evidence-based guidance. NHS England also looks at resilience from a clinician’s point of view and summarises the ‘Eight principles for being a resilient doctor’ which are set out by the Australian Medical Association. These principles focus on the changes that can be made in everyday life to help with developing resilience.

Resilience is mentioned a lot in relation to managing stress. It can be defined as “the ability to adapt and succeed in the face of adversity and stress”. A resilient person can maintain their wellbeing and continue moving forward when they are tested by life’s difficulties. Being resilient doesn’t come naturally to everyone and can be something to develop over time. The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development have produced ‘Developing resilience: a guide for practitioners’ which contains evidence-based guidance. NHS England also looks at resilience from a clinician’s point of view and summarises the ‘Eight principles for being a resilient doctor’ which are set out by the Australian Medical Association. These principles focus on the changes that can be made in everyday life to help with developing resilience.

Taking time to improve wellbeing can be a good stress-reliever. The New Economics Foundation (NEF) outlines ‘Five ways to wellbeing’, These consist of:

- Connect – Make time for family and friends. Build relationships with colleagues and neighbours. Become part of your local community.

- Take notice – Think about what matters to you most and take time to appreciate it. Be aware of your feelings and emotions. Try meditation and mindfulness.

- Keep learning – Try something new and embrace new experiences. Learning a new skill can boost your confidence and create an escape from stressors.

- Be active – Think about which physical activity you enjoy and that suits you. Regular exercise is associated with lower rates of depression and anxiety and helps to slow down age-related cognitive decline.

- Give – Do something nice for a friend or stranger or volunteer your time to the community. Feeling part of a wider community can be rewarding and build connections with those around you.

In order to ensure the wellbeing of doctors in their workplace, the GMC outline an ‘ABC of doctors’ core needs’. When these needs are met, it’s suggested that people are more motivated and have better overall health and wellbeing. Even if one of the needs is not met, it can have a negative impact on a doctor’s wellbeing and motivation. The following needs are taken from the GMC’s ‘Caring for doctors Caring for patients’ report10

- Autonomy or control – the need to have control over our work lives, and to act consistently with our work and life values.

- Belonging – the need to be connected to, cared for, and caring of others around us in the workplace and to feel valued, respected and supported.

- Competence – the need to experience effectiveness and deliver valued outcomes, such as high-quality care.

The RCGP recognises that being a GP is one of the most difficult jobs in medicine. As the first point of contact for most patients, a GP sees an average of 41 patients per day11. The RCGP’s ‘Fit for the Future’ campaign is the College’s vision for the future of general practice. It covers the changing role of the GP, the tools and skills needed to fulfil this role and the vision of an expanding general practice workforce. This campaign outlines the ways that primary care can adapt to ever-changing health needs and ultimately help to relieve the dangerous levels of stress that GPs currently face.

Further information about the ‘Fit for the Future’ campaign can be found here on the RCGP website.

Getting help

For any GPs who are struggling with the pressures of their role or showing signs of stress or burnout, the following resources may help:

For any GPs who are struggling with the pressures of their role or showing signs of stress or burnout, the following resources may help:

- NHS GP Health service – Confidential service for GPs and GP trainees in England. It can help with issues relating to mental health, including stress or depression, or addiction problems. It’s provided by health professionals with expertise in addressing the issues concerning doctors. The BMA also have a support service that is open to the whole of the UK.

- Online cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) – This can be accessed via your local ‘Improving Access to Psychological Therapies’ scheme in England. In Scotland, there are online self-help resources available on ‘Moodjuice’. The ‘Living Life to the Full’ website also contains many online CBT resources that are available throughout the UK.

- The Balint Society – The society aims to help all health and social care professionals in the UK better understand the emotional content of their patient relationships. As a member of the Balint Society you can join a ‘Balint group’, which is a gathering for members to discuss particularly difficult patient cases confidentially in a safe space.

- Mentoring – Becoming a mentor or mentee provides an opportunity to develop professionally and discuss any work-based issues. In either role, mentoring can be a great way to get further insights in to your own working situation, whilst having an impartial sounding board for any difficulties experienced in your role. You can find out more about The Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management (FMLM) mentoring scheme here. You can also contact your local RCGP Faculty to see if any local mentorship schemes are available. Further mentoring resources can be found on the BMA website.

- Mental health apps – A range of different apps that can help with anxiety, self-harm and exploring mindfulness are listed on the NHS website.

- Big White Wall – This website offers a support network, resources for self-management and live therapy via text, audio or secure video. It is accessible, for free, to UK serving personnel, veterans and their families, and some UK Universities and colleges. It is also available in some locations via the NHS. Eligibility can be checked via their website.

- The RCGP provides support and advice on GP wellbeing and mental health.

- A list of further support services that are specifically aimed at GPs in England can be found on the NHS website. If you are registered with GP Online, you can also access a list of support organisations on their website.

References

1 NHS Practitioner Health Service. 2018. The Wounded Healer: Report on the First 10 Years of Practitioner Health Service. [Online]. Available from: http://php.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/2018/10/PHP-report-web.pdf

2 Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System. 2017. Ninth National GP Worklife Survey. [Online]. Available from: http://blogs.lshtm.ac.uk/prucomm/files/2018/05/Ninth-National-GP-Worklife-Survey.pdf

3 The Commonwealth Fund. 2015. 2015 Commonwealth Fund International Survey of Primary Care Physicians in 10 Nations. [Online]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2015/dec/2015-commonwealth-fund-international-survey-primary-care-physicians

4 General Medical Council. 2018. The state of medical education and practice in the UK. [Online]. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/about/what-we-do-and-why/data-and-research/the-state-of-medical-education-and-practice-in-the-uk

5 British Medical Association. 2019. Caring for the mental health of the medical workforce. [Online]. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/collective%20voice/policy%20research/education%20and%20training/20190196%20bma%20mental%20health%20survey%20report.pdf?la=en

6 Royal College of General Practitioners Wales. 2018. Transforming general practice: Building a profession fit for the future. [Online]. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/RCGP-faculties-and-devolved-nations/RCGP-Wales/PDF-Documents/2018/RCGP-transforming-general-practice-dec-2018.ashx?la=en

7 Royal College of General Practitioners Scotland. 2019. From the Frontline. The Changing landscape of Scottish general practice. [Online]. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/RCGP-Faculties-and-Devolved-Nations/Scotland/RCGP-Scotland/2019/RCGP-scotland-frontline-june-2019

8 Royal College of General Practitioners Northern Ireland. 2019. Royal College of General Practitioners Northern Ireland GPs Survey. [Online]. Available from: https://www.comresglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/RCGP_ComRes_Northern-Ireland-GPs-Survey_Wave-4_Tables.pdf

9 NHS Digital. 2019. NHS Sickness Absence Rates, July 2019, Provisional Statistics. [Online]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-sickness-absence-rates/july-2019-provisional-statistics

10 General Medical Council. 2019. Caring for doctors Caring for patients. [Online]. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/caring-for-doctors-caring-for-patients_pdf-80706341.pdf

11 Pulse. 2018. GPs have almost twice the safe number of patient contacts a day. [Online]. Available from: http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/home/finance-and-practice-life-news/gps-have-almost-twice-the-safe-number-of-patient-contacts-a-day/20035863.article

Keeping track of your eLearning completions has just got easier. Our latest feature on the RCGP Online Learning Environment (OLE) is the eLearning portfolio – a direct link between your eLearning activity and the Clarity appraisal toolkit.

When preparing for your appraisal, it can be difficult to remember all of the learning you have completed in the past year, let alone how many CPD credits you have earned in the process. With this in mind, we have added a new portfolio section to keep everything in one place and to make it easier to upload to your Clarity account.

Your eLearning portfolio is conveniently located in the ‘Navigation’ block, which is visible at the side of the screen on various pages on the OLE. This means that you’re just one click away from your personal portfolio on pages such as the OLE homepage and the clinical content section. When accessing your portfolio for the first time, you will be asked to log in to your Clarity account to link with your eLearning account. After this initial log in to Clarity, your accounts will remain linked for the next 30 days.

For any user with a Clarity account, the eLearning portfolio will hold a record of your learning for the last 12 months with the option to export any items in this record to your Clarity appraisal toolkit. The portfolio will allow you to review all of the learning activities completed in this period, update the CPD credits you have earned for each one and also add in any reflective notes. From the portfolio you will also be able to view and download any certificates associated with the learning activities, saving you from having to go back in to each activity individually to find these. As with the certificates, if you have completed any sections on GP SelfTest your results will be available to view and download in the portfolio.

Any eLearning activity you complete on the OLE counts towards your CPD credits. The following activities will automatically appear in to your portfolio:

- eLearning courses

- Essential Knowledge Updates/Challenges

- GP SelfTest

Activities such as the ‘Five Minutes to Change your Practice’ screencasts and the eLearning podcast can be added manually to your portfolio to track how long you have spent on them. This also applies to any learning activities that don’t include certificates upon completion.

This new feature will be available to any users with a Clarity account from October 2019. For a demonstration on how to get started, you can view our FAQ video here.

You can find out more information on appraisal and revalidation for GPs here.

The presenting symptom of ‘dizziness’ is very common in primary care and vertigo is one of the two most common causes. A review of five studies of dizziness presentations showed around a third were found to have vertigo, with the prevalence increasing with age.2

The presenting symptom of ‘dizziness’ is very common in primary care and vertigo is one of the two most common causes. A review of five studies of dizziness presentations showed around a third were found to have vertigo, with the prevalence increasing with age.2

Vertigo is a symptom, not a condition in itself.2 It is a false sensation of a person or their surroundings moving or spinning, but with no actual physical movement1. It can be abrupt in onset and aggravated by head movements.1 The first step in making a diagnosis is to find out what the patient means by ‘dizzy’ and whether or not this represents vertigo.

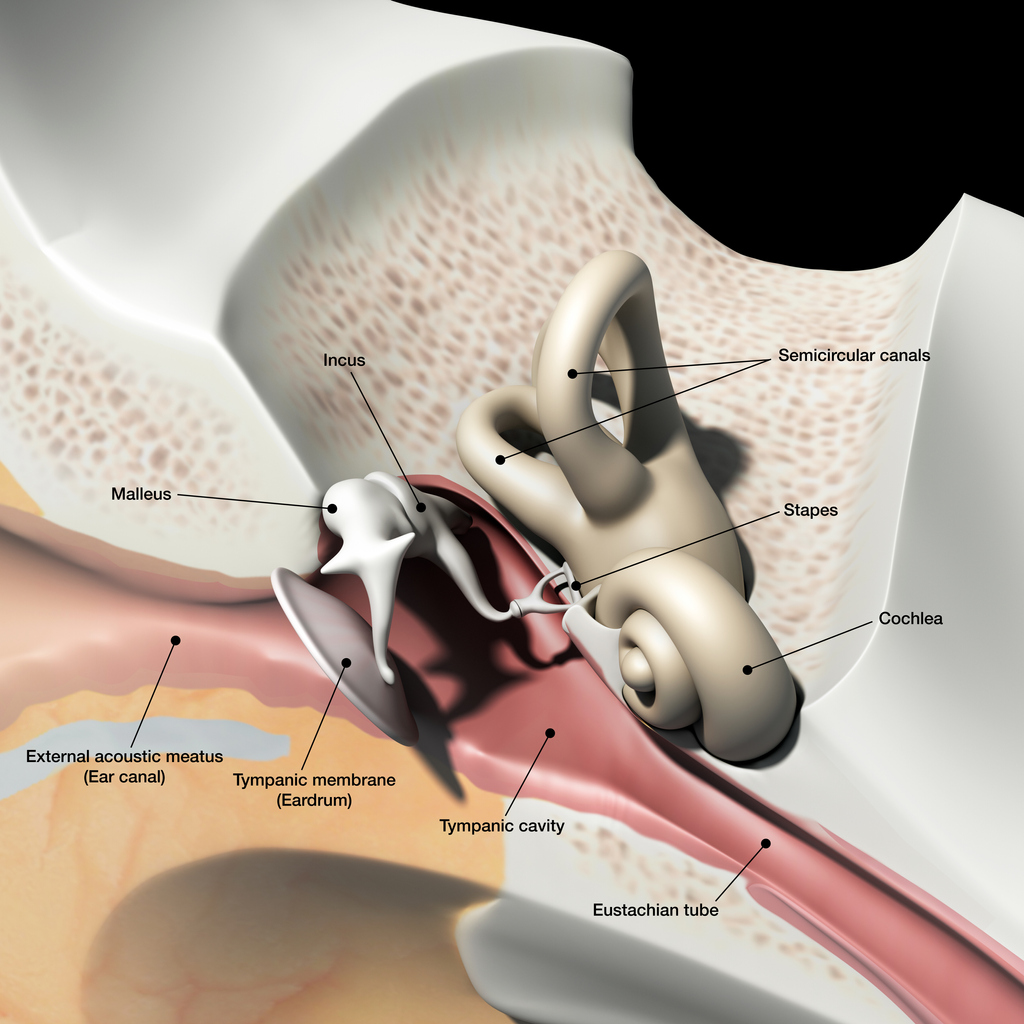

Vertigo is commonly caused by a problem with the inner ear (peripheral vertigo) or the brain (central vertigo)3. Types of peripheral and central vertigo are as follows:

Peripheral3:

Peripheral vertigo is a group of disorders or dysfunction of the vestibular labyrinth, semicircular canals or the vestibular nerve.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a type of peripheral vertigo and the most common cause of vertigo in general. BPPV involves short, intense, recurrent attacks, often accompanied by nausea. These attacks can last for several minutes or hours. BPPV develops when otoliths become detached from the utricular macula and migrate into one of the semicircular canals. Following head movement, otoliths are stimulated as they are move through the endolymph in the semicircular canals. The stimulation stops as movement ceases. When an otolith is detached, it may continue to move despite the head stopping. The sensation of ongoing movement which comes from the otolith conflicts with other sensory input, such as that from the eyes or proprioception, causing vertigo8.

Vestibular neuronitis is another inner ear condition that triggers symptoms of vertigo. It is almost always caused by a viral infection, which results in inflammation of the vestibular nerve. Symptoms of vestibular neuritis come on suddenly and can cause unsteadiness, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms usually last a few hours or days but can take up to six weeks to resolve completely.

Vestibular neuronitis and labyrinthitis are often used interchangeably, but in neuronitis only the vestibular nerve is inflamed; in labyrinthitis the labyrinth is affected as well. Vestibular neuritis is a very common cause of vertigo, labyrinthitis is much rarer, and because the cochlea is invariably involved, there is always some degree of hearing loss in labyrinthitis.

Ménière’s disease is a rare inner ear disorder which can cause vertigo. Along with tinnitus and hearing loss, patients experience sudden attacks of vertigo which can last for around two to three hours. These symptoms may take a couple of days to completely disappear.4 It is thought that Ménière’s disease is caused by a raised volume of fluid in the labyrinth, which causes distension. This can cause damage to, and thus dysfunction of, the vestibular system and the cochlea.9

Central2:

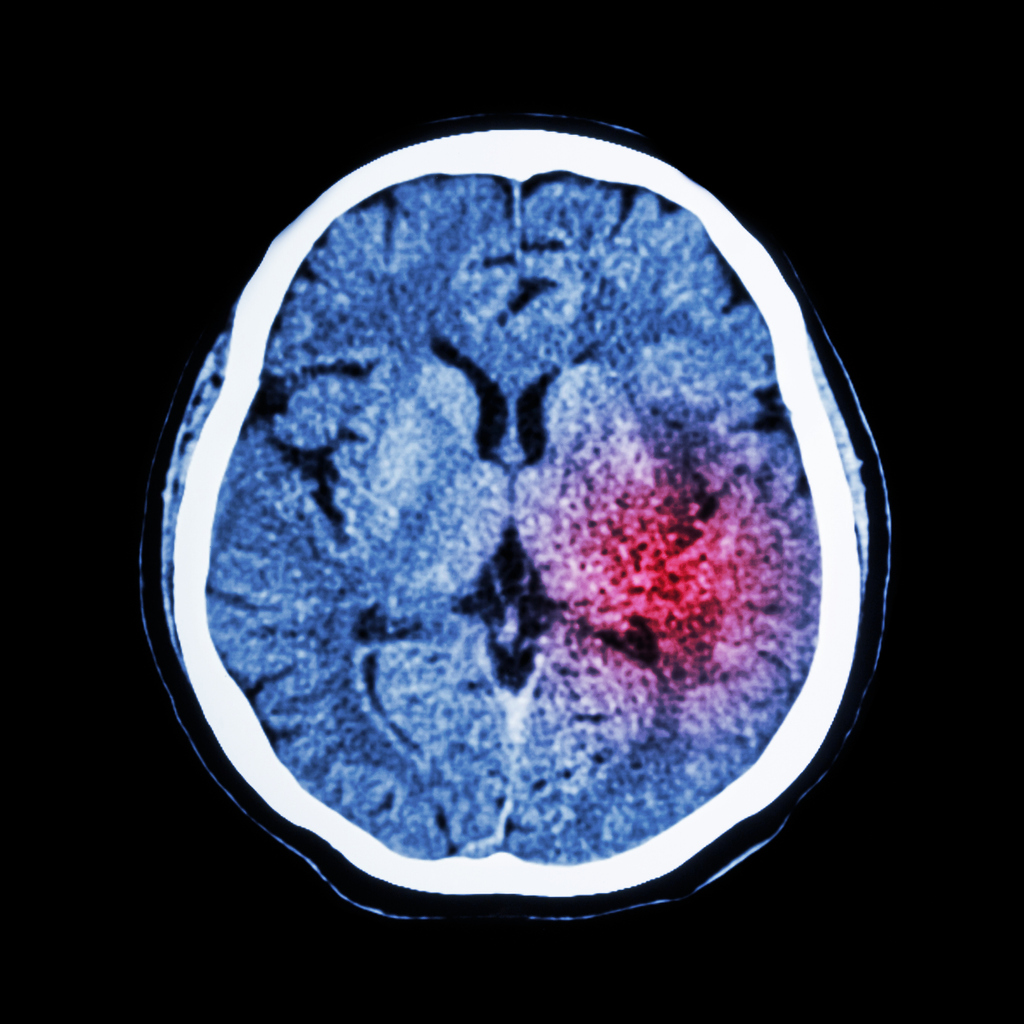

Central vertigo results from a disorder or dysfunction or the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, or brain stem.

Migraines are the most common cause of central vertigo. Vestibular migraines can cause ataxia, visual disturbances, occipital pain, nausea and vomiting.

Other less common causes of central vertigo include stroke and transient ischaemic attacks, brain tumours, multiple sclerosis and acoustic neuroma.

According to the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on Vertigo, the assessment of a person presenting with vertigo should consist of the following:

- description of the vertigo

- associated symptoms

- relevant medical history – including ear infections, migraine, head trauma and cardiovascular risks.

To distinguish between peripheral or central vertigo on examination, you can perform a rapid head impulse test. This test demonstrates the function of the peripheral vestibular system. If the test is abnormal, peripheral vertigo is suspected and if it is normal, central vertigo is suspected1,3.

The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre can also be used to determine a diagnosis of BBPV in patients with positional vertigo. This test reproduces the patient’s vertigo and possible nystagmus to determine which ear is abnormal and therefore causing the condition.

Treating central vertigo usually starts with treating the migraine, as this is the most common cause. This should usually relieve the vertigo symptoms5. If primary care treatments fail to treat these symptoms or a more serious pathology is suspected, referral to secondary care is recommended4. The urgency of the referral depends on the severity of the symptoms and what may be causing them2.

For peripheral vertigo, canalith repositioning procedures (CRPs) can be used to treat people with BPPV. It focuses on moving the dislodged otoconia back to their correct place in the ear6.

For peripheral vertigo, canalith repositioning procedures (CRPs) can be used to treat people with BPPV. It focuses on moving the dislodged otoconia back to their correct place in the ear6.

Epley manoeuvre: If the patient has positional vertigo and a positive Dix-Hallpike test, the Epley manoeuvre is indicated. It focuses on moving the otoconia back into the saccule. It can also be performed immediately after diagnostic tests and can be repeated if necessary to relieve symptoms. 74% of patients have total resolution of their symptoms within a week of the manoeuvre1. A diagram and step by step can be found here.

Brandt-Daroff: This is recommended if CRPs are ineffective or not suitable. Brandt-Daroff is a treatment for BPPV that can be performed at home without supervision. The repetitive movements encourage the otoconia to move back to their correct position in the inner ear. A step by step of the Brandt-Daroff exercises can be found here.

Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises: Management of the underlying cause of the vertigo is the first line treatment. However exercises such as Cawthorne-Cooksey are a form of vestibular rehabilitation which promote central compensation for vestibular dysfunction and offer treatment for chronic vertigo. Doing this may make the dizziness symptoms worse for a few days after the exercises, but perseverance may help to alleviate the symptoms over time6. Step by step instructions can be found here. BPPV and Ménière’s disease may not respond well to vestibular rehabilitation.

Medication is generally not recommended to treat vertigo. If a patient is waiting to be admitted to hospital or seen by a specialist, NICE recommend prescribing short-term symptomatic drug treatment to relieve symptoms of nausea and vomiting2. This is recommended for both central and peripheral vertigo if the patient is experiencing severe symptoms. To relieve severe symptoms rapidly, NICE suggest giving the patient buccal prochlorperazine, or a deep intramuscular injection of prochlorperazine or cyclizine. For less severe symptoms, short-term oral courses of vestibular sedatives, such as prochlorperazine, or cinnarizine, cyclizine, or promethazine teoclate (antihistamines) are recommended2. These vestibular sedatives help to suppress the receptors in the semi-circular canals of the inner ear and therefore reduce vestibular hyperactivity. These sedatives can ease the symptoms of dizziness and vomiting that vertigo can cause, but are not a long-term solution as they prolong the body’s readjustment after an instance of vertigo7.

References

1 Molnar A., et al. 2014. Diagnosing and Treating Dizziness. Medical Clinics, Volume 98, Issue 3, 583 – 596. Available at: https://www.medical.theclinics.com/article/S0025-7125(14)00029-7/fulltext

2 NICE. 2017. Clinical Knowledge Summary. Vertigo. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/vertigo

3 Northwestern University Emergency Medicine blog. 2018. Vertigo: A hint on the HiNTs exam. [Online] Available at: https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hints

4 NHS Inform. 2019. Meniere’s disease. [Online] Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/menieres-disease

5 NHS Inform. 2019. Vertigo. [Online]. Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/vertigo

6 Brain and Spine Foundation. 2017. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises. [Online] Available at: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/our-publications/our-fact-sheets/vestibular-rehabilitation-exercises/

7 ENT UK. 2017. Vertigo. [Online] Available at: https://www.entuk.org/vertigo

8 Payne, J. 2016. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo [Online] Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/benign-paroxysmal-positional-vertigo-pro

9 Henderson, R. 2015. Ménière’s Disease [Online] Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/menieres-disease-pro

May marks Action on Stroke Month, which is organised by the Stroke Association.

May marks Action on Stroke Month, which is organised by the Stroke Association.

In 2011, Public Health England launched the ‘FAST – Face-Arm-Speech-Time’ campaign to increase awareness of the signs of a stroke and fast access to treatment. Treating at 90 minutes will result in 10% more patients being independent at three months post-stroke than if treatment is given at three hours. Stroke is often thought of as an illness of old age but 10-15% of ischaemic strokes occur in young adults1. ‘Young adults’ are broadly defined as aged between 18-50 years of age2.

The worldwide incidence of ischaemic stroke in those aged 18-50 has increased up to 40% in recent decades, with around 2 million people suffering ischaemic stroke each year2. In England, approximately 57,000 people had a stroke for the first time in 2016, 3% of whom were aged under 403.

Strokes in younger adults have a more significant economic impact due to patients being left disabled during their most productive years1. The prevalence of vascular risk factors for stroke in younger adults can differ from those in older adults and may not be as routinely screened for. The primary stroke prevention strategy is to reduce potential risk factors such as:

Atrial fibrillation (AF)

There are around 1.4 million people with AF in the UK4. It is the most common cardiac arrhythmia contributing to significant morbidity and mortality5. A 2015 study found that around 10% of young stroke patients (≥50) had AF6. The risk of stroke increases five-fold for people with AF and it contributes to around one in five strokes. AF related strokes are often more severe and have higher mortality and disability rates7. However, a quarter of people with AF remain undiagnosed. Our RCGP eLearning course on AF contains more information on its management, anticoagulation and risk assessment.

Elevated Lipids

Hyperlipidaemia contributes to the development of atherosclerotic plaques, so statins are indicated for primary prevention when the 10 year risk of cardiovascular events is high. In secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke, a high intensity statin (such as atorvastatin 20-80mg daily) is used, with the aim of reducing non-HDL cholesterol by more than 40%8.

Hypertension

Hypertension affects around 9.5 million people in the UK and can triple the risk of stroke and heart disease9. Worldwide it is a contributing factor to approximately half of stroke episodes1. Lifestyle modifications, such as exercise, weight loss and reduced alcohol consumption, should be advised, but depending on an individual’s risk assessment, antihypertensives may be necessary.

Lifestyle

Factors such as obesity, smoking, drinking alcohol and using recreational drugs can increase the risk of stroke. Drugs such as cocaine can acutely and markedly increase blood pressure. This can then lead to both ischaemic or haemorrhagic strokes. It’s estimated that around 6 out of 10 young adults were regularly engaging in smoking, alcohol abuse or recreational drug use at the time of their stroke9.

GPs can play a key role in preventing a stroke in a young adult by detecting, treating and monitoring AF. The Stroke Association’s ‘Detect, Protect and Perfect’ AF toolkit details the ways that CCGs can implement policies to identify those with AF and reduce their stroke risk. The data in this document focuses on London CCGs but the methodologies and resources can be applied throughout the UK. Examples of other CCGs that have used ‘Detect Protect and Perfect’ can be found here. The Stroke Association’s ‘AF: How can we do better?’ document, which was produced in partnership with the RCGP and other health organisations, looks at data in England but includes key messages that can be applied in all four countries. Regular reviews are vital for patients with AF, and any patient aged under 50 who has a stroke or TIA should be tested for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Patients with thromboembolic events and women who have recurrent miscarriages should also be considered for a test for APS.

GPs can play a key role in preventing a stroke in a young adult by detecting, treating and monitoring AF. The Stroke Association’s ‘Detect, Protect and Perfect’ AF toolkit details the ways that CCGs can implement policies to identify those with AF and reduce their stroke risk. The data in this document focuses on London CCGs but the methodologies and resources can be applied throughout the UK. Examples of other CCGs that have used ‘Detect Protect and Perfect’ can be found here. The Stroke Association’s ‘AF: How can we do better?’ document, which was produced in partnership with the RCGP and other health organisations, looks at data in England but includes key messages that can be applied in all four countries. Regular reviews are vital for patients with AF, and any patient aged under 50 who has a stroke or TIA should be tested for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Patients with thromboembolic events and women who have recurrent miscarriages should also be considered for a test for APS.

For more information on stroke risks and contributing factors, you can access the following RCGP resources for free:

Atrial Fibrillation – 1 CPD point

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) – 0.5 CPD points

Alcohol: Identification and Brief Advice – 2 CPD points

Behaviour change and cancer prevention – 0.5 CPD points

Essentials of smoking cessation – 0.5 CPD points

Management of Obesity in General Practice – 5 minute screencast

RCGP members can also benefit from free access to the following resources:

EKU 4: Management of Patients with Stroke or TIA

EKU 15: Atrial fibrillation & New Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

References

1 Smajlović D. 2015. Strokes in young adults: epidemiology and prevention. Vascular health and risk management, 11, 157–164. DOI:10.2147/VHRM.S53203

2 Cited in: Ekker MS et al. 2018. Epidemiology, aetiology, and management of ischaemic stroke in young adults. The Lancet. Volume 17, issue 9, p790-801, 01 September 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30233-3

3 Public Health England. 2018. Briefing document: First incidence of stroke. Estimates for England 2007 to 2016. [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/678444/Stroke_incidence_briefing_document_2018.pdf

4 Stroke Association. 2018. AF: How can we do better? [Online] Available at: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/af-data_2018_england_eng_2.pdf

5 Aggarwal, N., Selvendran, S., Raphael, C. E., & Vassiliou, V. 2015. Atrial Fibrillation in the Young: A Neurologist's Nightmare. Neurology research international, 2015, 374352. doi:10.1155/2015/374352

6 Sanak D., Hutyra M., Kral M., et al. 2015. Atrial fibrillation in young ischemic stroke patients: an underestimated cause. European Neurology. 2015;73(3-4):158–163.

7 NICE. 2018. Atrial fibrillation. Scenario: First or new presentation of AF. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/atrial-fibrillation#!scenarioRecommendation:4

8 NICE. 2017. Clinical knowledge summary. Stroke and TIA. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/stroke-and-tia#!scenario:2

9 Cited in: Stroke Association, 2018. State of the nation. [Online] Available at: https://www.stroke.org.uk/system/files/sotn_2018.pdf

Allergy

Allergy