Person-Centred Care toolkit

| Site: | Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment |

| Course: | Clinical toolkits |

| Book: | Person-Centred Care toolkit |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 3 March 2026, 4:27 AM |

Description

The Person-Centred Care toolkit has been developed with NHS England to support GPs and primary care teams.

Introduction

The Person-Centred Care Toolkit has been developed with NHS England to support GPs and primary care teams deliver person-centred care.

People with multiple long-term conditions account for about 50% of all GP appointments but the current 10-minute GP consultation doesn't allow enough time to effectively address all health and well-being issues. The person-centred care approach gives people more choice and control in their lives by providing an approach that is appropriate to the individual's needs. It involves a conversation shift from asking 'what's the matter with you' to 'what matters to you'.

Person-centred care provides care that responds to individual personal preferences, needs and values and assures that what matters most to the person guides clinical decisions. It looks to build upon strengths, resources and skills that an individual, their carers, family and communities have in order to enable and empower people. It provides care which does things 'with' people rather than 'to' or 'for'

them.

Person centred care as a term describes the ethos and approach that enables this to happen. It requires a whole system and team approach, with all stakeholders valuing the principles and processes of person centred care, and all providers ensuring

their services are set up to deliver to these.

‘Person’ in this context refers to individual patients, but includes their carers and significant support networks if appropriate.

Key aspects of person-centred care include:

- Respect for the person’s values, preferences and expressed needs

- Personalised, co-ordinated and integrated health and social care and support

- Equal partnership in the relationship between health care professionals and patients

- Involvement of family, friends and carers

- Continuity of care

- High quality education and information.

Person-centred care resonates with the Wanless concept of a ‘fully engaged population’, with all the associated health, wellbeing and economic benefits. Using a person-centred approach has been shown to benefit patients, health professionals and health systems as well as reduce health inequalities. One of the key shifts in person-centre care is moving from a reactive to a proactive model where preparation is key, something that requires a change in processes.

It can improve concordance between the health professional and individual thereby improving the working relationship, health outcomes and GP job satisfaction as well as reducing the demand on primary care.

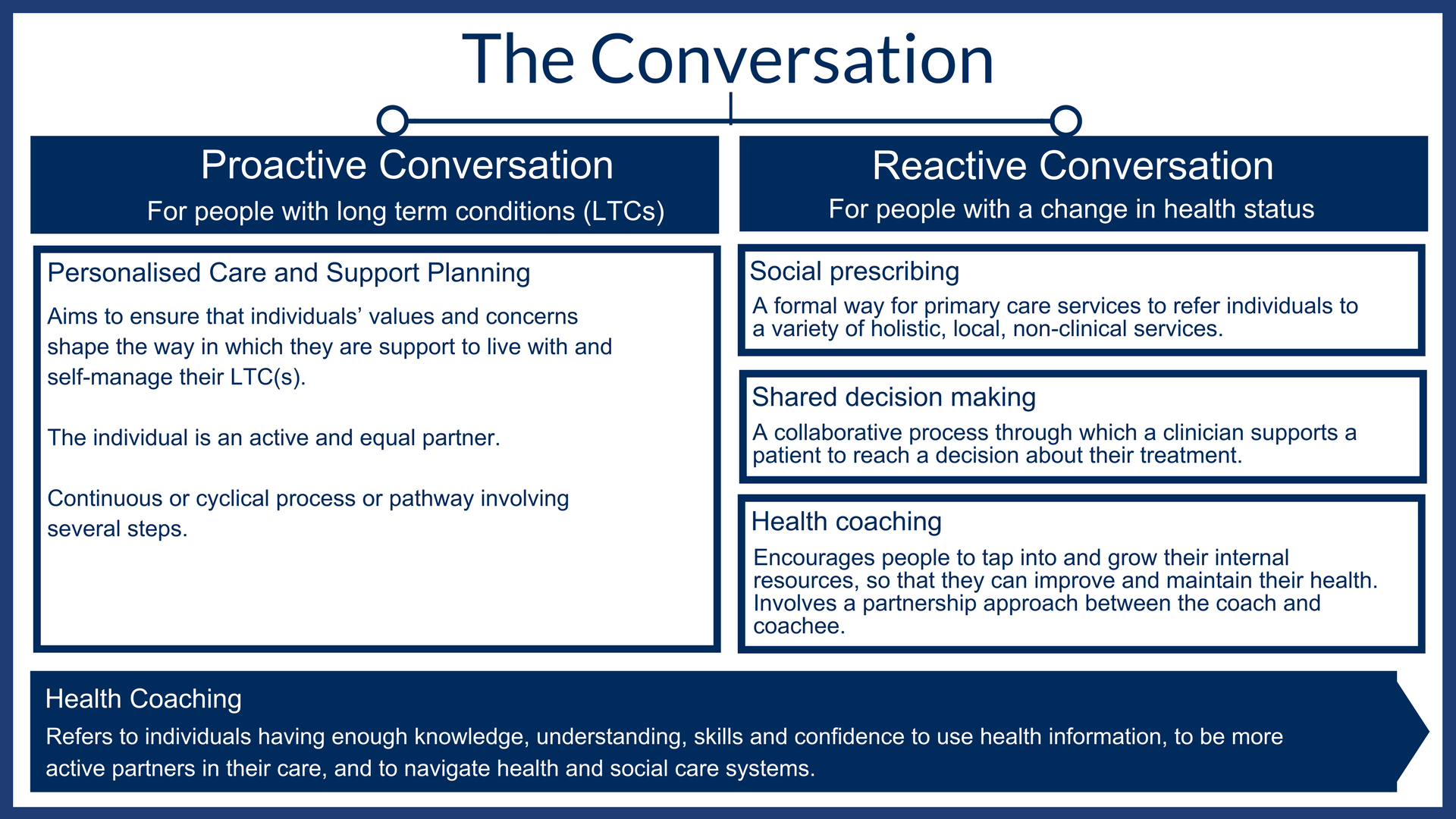

Key tools include social prescribing, collaborative care and support planning, shared decision making and health coaching.

This toolkit has been developed in partnership between the RCGP and NHS England.

Please send any feedback or suggestions to innovation@rcgp.org.uk

The Conversations

The conversation starts with what matters to the person, what is working and not working for them, and where they want to be in the future – therefore setting their agenda, and moving towards the outcomes that the person wants to achieve.

There are broadly two type of conversation to be considered: reactive and proactive. Proactive conversations involve identifying individuals who may benefit from primary care support planning. Although there are a number of methods for doing this (PCSP guidance), the multidisciplinary team should be trained and engaged for the process to be most effective.

For proactive conversations, both the practitioner and person need to be prepared by sharing information beforehand and allowing time for reflection. Techniques such as shared decision making and health coaching as well as the use of social prescribing are pivotal to both proactive and reactive conversations.

Case Studies

- A Proactive Conversation [PDF]

- A Reactive Conversation [PDF]

Social Prescribing

Social prescribing creates a formal way for primary care services to refer patients with social, emotional or practical needs to a variety of holistic, local, non-clinical services. In doing so, it also aims to support individuals to take greater control of their own health.

Social prescribing is sometimes referred to as a ‘community referral’ and often involves a link worker or navigator who helps to design a package of services or activities to meet their needs.

Providers of social prescribing should be able to ‘co-design’ solutions for people that consider the wider determinants of their health and help people to choose activities that address these needs. This might consider factors such as enabling people to engage with communities, be more active and eat more healthily, as well as many other priorities agreed together with the person.

Social prescribing encompasses prevention and early intervention as well as supporting the management and promotion of self-care for people with long term conditions, all of which can help to reduce future demand on primary care services.

Activities and services are often provided by voluntary and community sector organisations. The services available vary from sports, leisure and the arts, or activities to interventions focused on the development of skills or education.

Examples of social prescribing include:

- 'Museums on Prescription’ scheme

- Walking for Health’ run by The Ramblers and Macmillan Cancer Support

- Community Choirs run by The Stroke Association or Alzheimer’s Society

- Eco-therapy or ‘green prescriptions’

Resources

- The King's Fund: What is social prescribing?

- Health Education England: Social prescribing at a glance

- The Work Foundation: Social prescribing, a pathway to work?

- Nesta: More Than Medicine - new services for people powered health

- Social prescribing network

- National Voices: What is the role of VCSE organisations in care and support planning?

- NHS England: Social Prescribing

As part of our Person-Centred Care activities with NHS England, we are undertaking a project ‘Exploring approaches to measure the use and impact of social prescribing’. This work is undertaken through the RCGP Research and Surveillance Centre (RCGP RSC), in collaboration with the University of Oxford. The Social Prescribing Observatory has been published online and practice level dashboards are available to members of the RSC network. For more information or to sign up to the RSC network, please contact research@rcgp.org.uk.

Health Literacy

Health literacy refers to individuals having enough knowledge, understanding, skills and confidence to use health information, to be more active partners in their care, and to navigate health and social care systems.

Research has shown that 43% of working-age adults in England have low health literacy. This figure rises to 61% if numeracy is involved.

Health literacy is not restricted to the person’s ability to read and write and does not only apply to the written word. It also encompasses computer and numerical literacy and the ability to interpret graphs and visual information. It also recognises that our health systems are often very hard for people to navigate.

The teach back method is a useful way to confirm that the information provided is being understood by getting people to 'teach back' what has been discussed. Chunk and check can be used alongside teach back and requires break down of information into smaller chunks throughout consultations and check for understanding along the way rather than providing all information that is to be remembered at the end of the session.

Health literacy affects people’s ability to:

- Engage in self-care and chronic disease management

- Share information such as medical history with professionals

- Navigate the healthcare system such as locating services and filling in forms

- Understand concepts such as probability and risk

- Evaluate information for quality and credibility

As a result, individuals with low health literacy are:

- More likely to have emergency and avoidable admissions

- Less likely to engage with health promotional activities such as vaccination

- Less likely to adhere to treatment

The complex nature of health literacy requires a multi-faceted approach which addresses individual and community limitations, education and training of professionals as well as the resources available and peer support to assist.

Examples

Health literacy affects people’s ability to:

- Teach back initiative in Stoke on Trent: clinicians invite patients to explain in their own words what’s been discussed.

- Browsealoud: free-to-use NHS support tool which reads aloud and translates webpage content.

Resource

- Health Education England: Health literacy

- The Health Literacy Place: Materials and resources for use

- Patient Information Forum: Health literacy

Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making is a process in which clinicians and patients work together to make decisions and select tests, treatments and care plans. It places equal value on the priorities, values and preferences of the patient, and the expert knowledge of the health care professional.

It is a move away from a paternalistic approach and informed decision making.

Benefits of shared decision making include:

- Increased patient involvement and engagement and

- Improved adherence to treatment

- Less anxiety about the care process

- Increased satisfaction about treatment outcomes

Patient Decision Aids are specifically designed resources which help patients make difficult decisions about healthcare options. One example is the NHS Shared Decision App.

Resources

- The King's Fund: Making shared decision making a reality

- NICE: Shared decision making

- The Health Foundation: Shared decision making

- RCGP: Personal Health Budgets

Health Coaching

The founding premise of coaching is a belief that everybody is resourceful to some degree. The process of health coaching is to encourage people to tap into and grow their internal resources, so that they can improve and maintain their health.

It involves a partnership approach between the coach and coachee, agreeing topics to focus on, and outcomes that matter to the person. Time is spent exploring the person’s reality to help them come up with their own ideas and plans to achieve their goals.

Key characteristics of health coaching include:

- A focus on the individual’s goals

- An approach in which both the person and professional are seen as experts, the person as an expert in their conditions and the professional as an expert in healthcare

- Support is tailored around the capabilities the person, and their assets within their context

- Breaking down of goals into manageable steps

The principles and techniques of health coaching can support other conversations. Health coaching mindset, skills and techniques can facilitate proactive conversations to make primary care support planning more effective.

Resources

- Nesta: Health coaching

- Health Education England: Health coaching for behaviour change

- The Health Coaching Coalition: Better conversation tools for action

- Better Conversation: Health coaching and care and support planning

Personal Health Budgets

Background and overview

Personal Health Budgets (PHBs) aim to give individuals with long term conditions and disabilities in England more control over the money spent on their health and wellbeing needs.

A personal health budget is not new money, but rather enables people to use funding in different ways that work for them.

Health professional work collaboratively with PHB recipients to ensure budgets are spent on evidence-based approaches. Joint reviews are also integral to ensure PHBs are spent on progression towards reaching personal health goals.

Who can have a Personal Health Budget?

Adults in England who are eligible for NHS Continuing Healthcare and children in receipt of continuing care have had the right to have a PHB since October 2014. The expansion of Personal Health Budgets extends the option of a budget to all those who evidence indicates could benefit.

What are the key principles of Personal Health Budgets?

- The person knows how much they have available for healthcare and support within the budget.

- The person is involved in the design of the care plan.

- The person is able to choose how they would like to manage and spend their budget, as agreed in the care plan.

How do Personal Health Budgets work?

A PHB can be used for a variety of services, activities, personal care, equipment and therapies in order to meet agreed health and wellbeing outcomes. Collaborative Care and Support Planning (CCSP) is a pivotal aspect of the process to ensure that PHBs work well. A good care and support planning discussion will identify a person’s strengths, skills and personal circumstances as well as their health needs. It will identify what is working and not working from their perspective, what is important to the person and what is important for their health.

The individual knows upfront how much money they have available for healthcare and support. All personal health budgets must be agreed and signed off by the person’s NHS team. An important part of the personal health budget process is monitoring and review. This is a chance to look at whether the care plan is working for the person and their family.

How much money does an individual get in their Personal Health Budget?

The amount that someone receives in their personal health budget will depend on the assessment of their health and wellbeing needs and the cost of meeting these needs.

How is the money managed?

The person has the option of:

- Managing the money as a direct payment: The individual receives the funds via a payment card or into a dedicated bank account.

- A notional budget. No money changes hands. The NHS is responsible for holding the money and arranging the agreed care and support.

- A third party budget: A different organisation holds the money for the individual, helps them decide what they need, and then they support the individual to access the services they have chosen.

A combination of the above approaches can be used.

Are Personal Health Budgets Compulsory?

Personal health budgets are purely voluntary. No one will ever be forced to take more control than they want.

What can a Personal Health Budget NOT be used for?

A personal health budget cannot be used to pay for alcohol, tobacco, gambling or debt repayment, or anything that is illegal. It cannot be used to buy emergency care, primary care services or medication.

Are Personal Health Budgets safe?

PHBs involve individuals taking greater responsibility for their care and taking positive risks that can help them live a better life. Possible risks, and the plans for how they will be managed, need to be recorded in an individual’s care plan. Individuals can also plan for periods of fluctuation by recording the care and support they require when their condition deteriorates.

What is Integrated Personal Commissioning (IPC)?

Sitting alongside PHB is the Integrated Personal Commissioning (IPC) programme which will, for the first time, blend comprehensive health and social care funding for individuals, and allow them to direct how it is used. It is one of the pillars of the Five Year Forward View. The programme is aimed at those groups of individuals who have high levels of need, often with both health and social care needs.

Resources

The Consultation

Proactive Care planning (PCP) is a proactive process (also referred to as Collaborative Care and Support Planning and Primary Care Support Planning), different from the traditional medical model, but a process with a purpose in supporting the "strength" based approach with three key objectives:

- To give people with long term conditions a greater sense of control over their lives and health by focusing on what is important to them and increasing their knowledge, skills and confidence to self-care (sometimes described as ‘activation’)

- Changing to a more productive consultation with the person as a consequence of proactive preparation by the clinician and the person themselves.

- To promote social prescribing as being of equal importance to the more traditional medical response.

The outcome is a single plan, no matter how many conditions or issues have been identified, which should be reviewed regularly. This reflects the fact that PCP is a continuous process, not a one-off event.

While the plan is an important and useful document, it is the personalised care and support planning process as well as conversation which are fundamental to this approach.

This toolkit provides a collection of relevant tools and information to assist members of the primary care team to implement the six-step model of collaborative care and support planning.

Resources

The Evidence

There is a general consensus that a person-centred approach can achieve better outcomes for patients, greater job satisfaction for health and care professionals, improved efficiency for health and care economies and healthier communities.

There is a growing body of evidence advocating a cultural shift towards PCP in the NHS.

Successful delivery of PCP requires a whole-system approach with organisational changes which work from the ‘bottom up’ [PDF]

Resources

- National Voices: Person-centred care in 2017, Evidence from service users

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Promoting person-centred care at the front line

- BMJ: Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients

- BMJ: Supporting patients to make the best decisions

- The Salzburg Statement on Shared Decision Making

- The King's Fund: How to deliver high quality, patient-centred, cost-effective care

- NICE: Community engagement: improving health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities

- NESTA: The Business Case for People Powered Health

- British Geriatric Society: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Toolkit for Primary Care Practice

Health Foundation

- Helping measure person-centred care

- Do changes to patient-provider relationships improve quality and save money?

- At the heart of health: Realising the value of people and communities

- Person-centred care: from ideas to action

- Evidence: Helping people help themselves

- Evidence: Helping people share decision making

- Realising the value

Resources

The RCGP has collaborated with GPs, health professionals and the voluntary sector across the country to produce a number of resources for individuals and organisations interested in Person-Centred Care, including our Person-Centred Care Toolkit, training videos and more.

Person-Centred Care Training Videos

The RCGP Innovation team has worked closely with GPs, health professionals and the voluntary sector across the country to produce a series of training videos showing different models of Person-Centred Care, specifically through the lens of social prescribing. The videos are examples of challenges, positive experiences, and how to approach things from a person-centred, professional perspective and system perspective.

Case Studies

- Person-Centred Care Case Study 1: Julie's Patient Participation Groups

Two events were held, bringing together patients, the local population and community/voluntary organisations.

- Person-Centred Care Case Study 2: Kay's Staff Training

Reception staff asked patients about their presenting issues to ensure they would see the most appropriate person.

- Person-Centred Care Case Study 3: Mohan-pal's Extended Consultations

Patients were offered a single forty-five minute appointment to support them to take charge of their problems.

- Person-Centred Care Case Study 4: Emily's Group Consultations

Innovative group consultations were introduced to five surgeries in Croydon.

- Person-Centred Care Case Study 5: Sarah's Social Enterprise

EHCAP aims to deliver Emotion Coaching training to the children and young people’s workforce across Somerset.

- Person-Centred Care Case Study 6: Katie's Two-Stage Approach

After an initial appointment with a health care assistant, patients would see a GP or practice nurse for a collaborative care and support planning consultation.

Pathways

The RCGP has also examined clinical pathways for four of the clinical priority areas identified in the NHS Forward View, all of which are unified by their impact on individuals, communities and services. Diabetes, learning disabilities, cancer and mental health represent a large proportion of patient contacts in primary care, with individuals often having multimorbidity.

Person-Centred Care Guidance

- Stepping Forward: Commissioning principles for collaborative care and support planning [PDF]

- RCGP Responding to the needs of patients with multimorbidity: A vision for general practice

- Care Planning Improving the lives of People with Long Term Conditions summary[PDF]

- Collaborative Care and Support Planning: Ready to be a reality [PDF]

- Richmond Group of Charities Taskforce on Multiple Conditions

Associated Organisations

- NHS England

- Coalition for Collaborative Care

- The House of Care approach

- Health Foundation Knowledge Resource Centre

- National Voices Guide to Care and Support Planning

For further information, please contact personcentredcare@rcgp.org.uk