Deafness and hearing loss toolkit

| Site: | Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment |

| Course: | Clinical toolkits |

| Book: | Deafness and hearing loss toolkit |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:16 PM |

Description

Guidance for GPs on the care of patients dealing with deafness and hearing loss.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Overview and facts

- Preventing Hearing Loss

- Signs of hearing loss

- Hearing Loss Overview

- Common symptoms table – How patient may present

- Common Red Flags and Referral Guidelines Timeline

- Referral Pathways

- Information and Support for Patients and Carers

- Psychosocial Effects of Hearing Loss

- Hearing Loss and the risk of developing dementia

- Interpretation of Investigations

- Balance differentials

- Tinnitus Management

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

- Paediatric Hearing - Foreign Body

- Paediatric Hearing - Otitis Externa (Swimmers Ear)

- Paediatric Hearing - Otitis Media with Effusion (Glue Ear)

- Meniere’s Disease

- Aural Care

- Assistive Technology

- Communication Tips

- Practical Tips for your GP Surgery

- Hearing Loss a Global Problem

- Information for NHS Managers and Commissioning Organisations

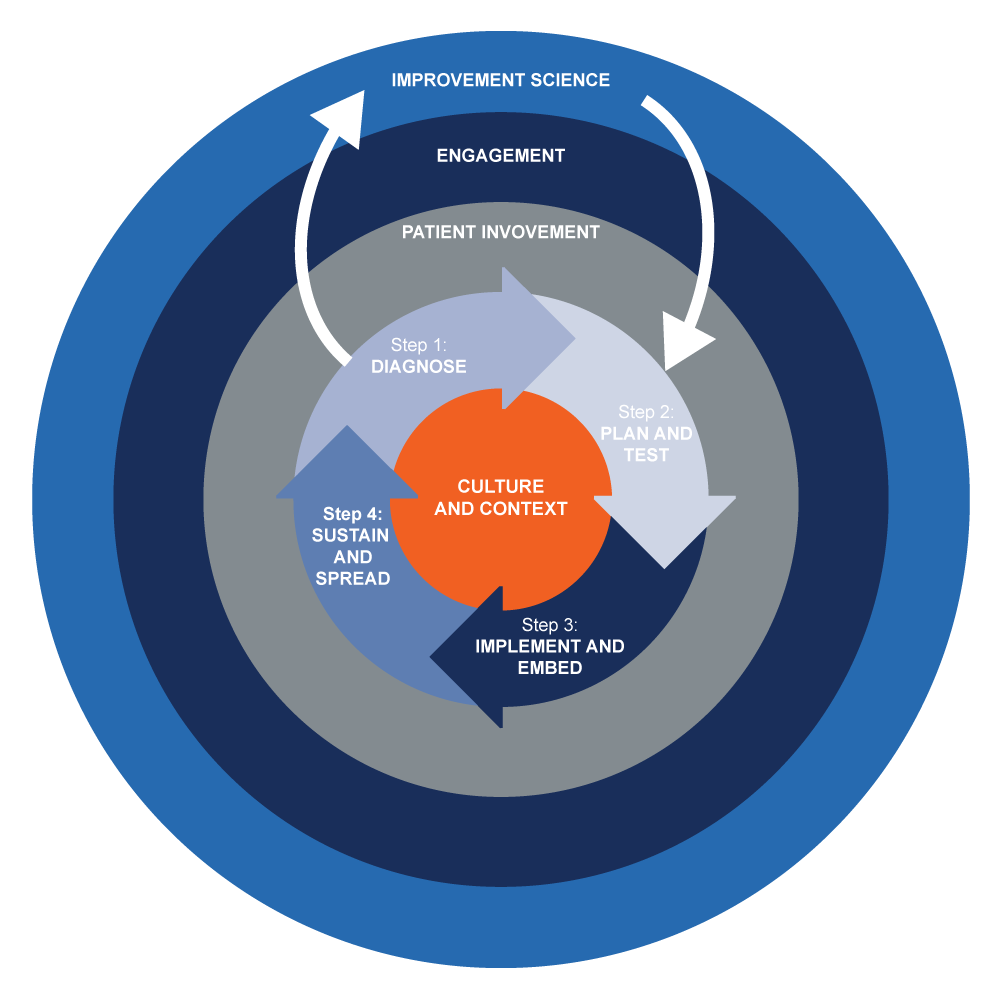

- Quality Improvement Initiatives

- GPVTS Teaching and Curriculum

- RCGP Learning: Essential CPD for Primary Care

- Examples of Innovation

- Podcasts

- COVID-19 and Patients with Deafness and Hearing Loss

- Further Reading

Introduction

There are 12 million people with hearing loss across the UK and this is expected to increase to 14.2 million by 2035. Hearing impairment can have a major impact on daily functioning and quality of life. It can affect communication, social interactions and work leading to loneliness, emotional distress and depression. The toolkit supports GPs and GP trainees to implement the latest NICE guidelines and NHS Accessibility Quality Standard and guidance across the UK. The resources developed aim to educate GPs and trainees on Deafness and hearing loss, help reduce variations in accessibility to GP practices and ensure Deafness and hearing loss are considered across all aspects of primary care activity including consultations and continued care.

The RCGP Deafness and hearing loss project team, led by Dr Devina Maru, RCGP Clinical Champion for Deafness and hearing loss, collaborated with The Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID) and NHS England and Improvement in developing the toolkit. This project was funded, thanks to an external educational grant from the British Irish Hearing Manufacturers Association (BIHIMA) in accordance with the RCGP’s sponsorship policy.

Resources include an Essential Knowledge Update (EKU) Screencast, GPVTS Teaching PowerPoint, Podcasts, EKU Online eLearning Module, Hearing Friendly Practice Animation Video and much more.

RCGP webinar: Deafness and hearing loss: changing mindsets, March 2024

Overview and facts

Terminology

These are generally accepted definitions for a person’s hearing loss but please note definitions are not always clear cut.

Regardless of how they identify, individuals may use a combination sign language, speech, hearing aids, cochlear implants, lip reading (synonymously used with speech reading) etc. to communicate effectively. Also, they may or may not use their voice.

- deaf (lower case ‘d’) - people who have hearing loss, whether at birth or acquired later through injury, disease or associated with ageing. They may communicate orally and may also be users of sign language.

- Deaf (upper case ‘D’) - deaf individuals who identify as being part of the Deaf community and who communicate almost exclusively with sign language.

- Hard of hearing - people who have lost some but not all hearing.

- Hearing impaired - anyone with any level of hearing loss.

- Acquired hearing loss - people who were born with hearing but have lost some or all of their hearing.

- Congenital hearing loss - born with hearing loss which may become progressively worse.

- Deafened - people who were born with hearing and have lost most or all of their hearing later in life.

References

- Hearing Link: Facts about deafness and hearing loss

- UCL: Deaf Awareness - Online Training for Doctors

Facts and figures

- Globally, over 80% of ear and hearing care needs remain unmet. Over 5% of the world’s population (430 million people) require rehabilitation to address their disabling hearing loss.

- 12 million adults in the UK are deaf, have hearing loss or tinnitus. That is roughly 10.1 million people in England, 1 million people in Scotland, 610,000 people in Wales and 320,000 people in Northern Ireland.

- By 2035, we estimate there’ll be around 14.2 million adults with hearing loss greater than 25 dB HL across the UK.

- 6.7 million could benefit from hearing aids but only about two million people use them.

- Unassisted hearing loss have a significant impact on older people leading to social isolation, depression, reduced quality of life and loss of independence and mobility.

- About 12,000 people in the UK use cochlear implants.

- Many people with hearing loss also have tinnitus which affects one in 10 adults. They may also have balance difficulties.

- Evidence suggests that people wait on average

10 years before seeking help for their hearing loss.

- The employment rate for those with hearing loss is 65%, compared to 79% of people with no long-term health issue or disability.

- Recent estimates suggest that the UK economy loses £25 billion a year in lost productivity and unemployment due to hearing loss.

References

- Hearing Link: facts about deafness and hearing loss

- WHO: Deafness and hearing loss - key facts

- RNID: Facts and figures

Legislation

There are legal requirements around disability rights and access.

Accessible Information Standard (AIS)

From August 2016, all NHS care or other publicly funded adult social care providers must meet the terms of the Accessible Information Standard (section 250 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012).

This legislation is designed to ensure that people with disabilities, impairments or sensory loss can get information in a form they can access and understand and are provided by health and social care providers with the professional communication support services they require.

During CQC inspections, five steps of Accessible Information Standard will be looked at by talking to the staff and people using the service and asking providers how they are meeting the AIS through annual provider information requests/collections:

- Identify

- Record

- Flag

- Share

- Meet

Equality Act 2010

Equality Act 2010 (applies in England, Wales, Scotland) combined and replaced previous discrimination legislation, including the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 still remains in Northern Ireland. It offers protection against discrimination to those with protected characteristics. These include age, disability, gender reassignment, race, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation, marriage and civil partnership, and pregnancy and maternity.

Deafness and Hearing Loss is a disability. To ensure disabled people can use services to a similar standard (as much as possible) as their non-disabled counterparts, service providers are required to make reasonable adjustments.

Recognition of British Sign Language (BSL)

The British Government on 18 March 2003 made a formal statement recognising BSL as a language in its own right.

The British Sign Language (Scotland) Act 2015 acted to promote the use of BSL and making provision for the preparation and publication of a British Sign Language National Plan for Scotland.

The UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (121 KB PDF) includes specific mention of rights to sign language use.

Research

- Access All Areas Report [PDF] - report into the experiences of people with hearing loss when accessing healthcare including contacting their GP surgery, consultations with medical staff and access to pharmacies.

- Hearing Matters Report [PDF] - report analysing the scale and impact of hearing loss in the UK and sets out what needs to be done by Government in tackling hearing loss.

- Sick of It Report - how the health service is failing Deaf people and suggestions as a 'prescription for change'.

Preventing Hearing Loss

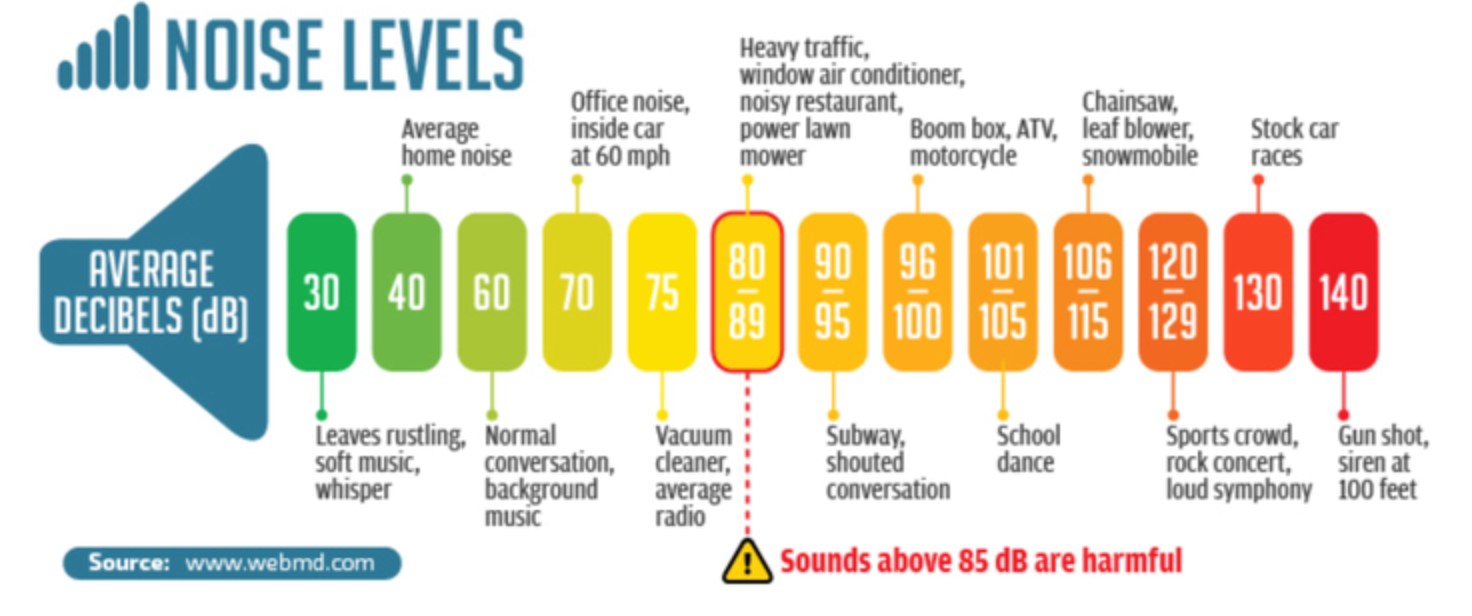

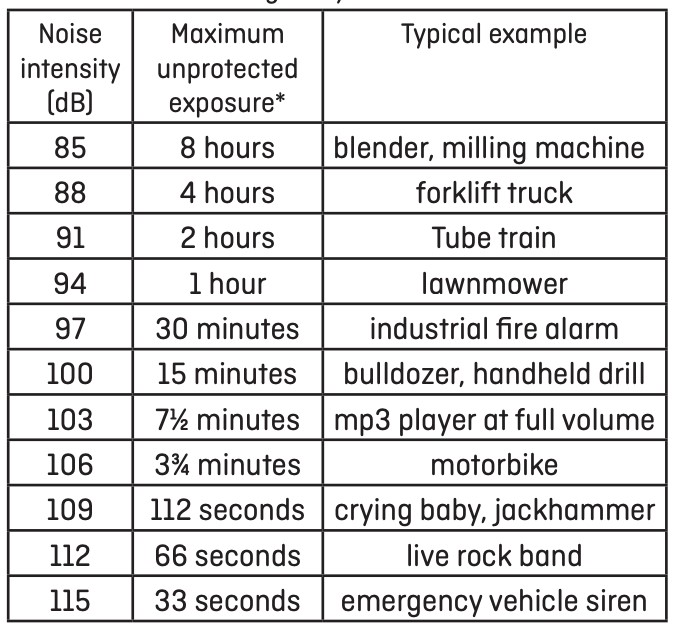

A decibel dB, is the unit used to measure the intensity of a sound – 85dBA and above is the level at which noise becomes unsafe without the use of hearing protection

The ‘dosage’ of noise exposure is dependent on two main things:

- the ‘volume’ or intensity of the noise

- the time or duration of the exposure to that noise.

The British Tinnitus Association has produced some guidance on 'how loud is loud'.

Identifying loud noise

- If you have to shout to be heard by somebody around a metre away, the background noise is loud enough to be potentially damaging.

- If your hearing is dulled after exposing yourself to noise, then your hearing has been damaged. This may be temporary, but if you expose yourself repeatedly to these situations, the damage may become permanent.

- If you find a ringing or buzzing in your ears (tinnitus) after exposing yourself to noise, then the noise is likely to have been damagingly loud.

- If a sound is painfully or uncomfortably loud, stop exposure immediately.

Consequences

- Hearing loss at certain frequencies. If noise is the suspected cause, this is termed noise-induced hearing loss.

- The hearing loss can be temporary, and recover within a day or two, or permanent, and not recover at all.

- If temporary, it should be taken as a warning that permanent damage is likely if this exposure is repeated.

- Loud noise exposure can sometimes cause a ringing or buzzing in the ears called tinnitus. Sometimes tinnitus goes away after a few minutes or hours after a loud noise exposure. However, sometimes it can persist for weeks, years, or even indefinitely, especially if you have a noise-induced hearing loss.

Prevention Tips

World Health Organization (WHO) has launched 'hearWHO', a free application for mobile devices which allows people to check their hearing regularly and intervene early in case of hearing loss. The app is targeted at those who are at risk of hearing loss or who already experience some of the symptoms related to hearing loss.

- Remove yourself from the noise, reducing the time of exposure

- Take frequent breaks from the loud noise if you cannot remove yourself from the noise

- If you know you will be in a noisy environment wear hearing protection to reduce the intensity of the noise eg. ear plugs or ear defenders

- Limit the time and volume when listening to music through earbuds or headphones. As earbuds are placed directly into the ear this can boost the audio signal by as many as 9dB. Larger earmuff-style headphones are to be preferred. Another protective measure is to adhere to the 60/60 rule, which simply put means never turn your volume up past 60%, and only listen to music with earbuds for a maximum of sixty minutes per day. You can also get noise-cancelling headphones which will allow you to listen to music for a longer extension of time, at a much lower decibel level

- At work your employer has a responsibility to protect your hearing and you should be issued with hearing protection if the noises you are exposed to are loud enough to be damaging. You must wear this hearing protection if it is issued.

References

Signs of hearing loss

Hearing loss can affect people of any age. The prevalence of hearing loss increases exponentially with age and approximately 42% of individuals over the age of 50 and 71% of individuals over the age of 70 have some degree of hearing impairment. Only one third of individuals who could benefit from hearing aids in the UK wear them.

Most age-related hearing loss is a gradual process, and often individuals will not notice that they are having difficulty hearing. Relatives, friends or carers may be the first people to notice that an individual may have a hearing loss. It is important to remember that even if someone can communicate on a one to one basis, in a quiet room without difficulty, that they may still have a hearing loss that will benefit from hearing aids.

It is important not to disregard communication difficulties as a dementia and behavioural related issue.

More information:

Potential indicators for hearing loss

- Age 50+

- Difficulty hearing in background noise such as pubs and restaurants

- Having to turn the TV up so that others complain about the volume

- Asking people to repeat themselves

- Unaware of conversation when the speaker is not facing the individual

- Speech sounds muffled or people do not speak clearly

- Avoiding social situations

- Withdrawal from conversation

- Mishearing, and inappropriate responding

- Unable to hear bird song

- Reporting tinnitus- noises in the ear, ringing, buzzing, whooshing etc.

- Difficulty hearing on the telephone

Other risk factors

- Family history

- History of occupational or social noise exposure

- Ototoxic medication- aminoglycosides (such as gentamicin) or chemotherapy drugs (platinum-based chemotherapy)

- Medical history: diabetes, cardiovascular disease and stroke, and autoimmune disorders

References:

- RNID: Facts and figures

- NHS England: Action plan for hearing loss

- Hearing Link: Facts about deafness and hearing loss

- The Lancet: Dementia prevention, intervention, and care

- RNID: Signs of hearing loss

- RNID: Other conditions that can affect hearing

- Mayo Clinic: Hearing loss

- Devina Maru and Ghada Al-Malky: Current practice of ototoxicity management across the United Kingdom (UK)

- Nice guideline [NG98]: Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management

Hearing Loss Overview

Key features

Epidemiology

- 12 million people with hearing loss in the UK

- 7 million could benefit from hearing aids

- Many also have tinnitus

- 42% of over 50s; 71% of over 70s have some hearing loss

Terminology

- Deaf: identify as part of Deaf community, communicate mostly with sign language

- deaf: people with hearing loss, communicate orally or with sign language

Consequences

- Hearing loss doubles risk of depression; increases mental illness prevalence

- Risk factor for developing dementia – reduced by hearing aid use

Clinical

Preventing hearing loss

- Volume and exposure duration are important

- Sounds above 85dB are harmful

- Shouting to be heard 1m away indicates potentially damaging background noise

Signs of hearing loss

- Hearing difficulties in places with background noise

- Turning TV up too loud for others

- Mishearing, asking for repetition

- Cannot hear birdsong

- Reporting tinnitus

Red flags

- Aysmmetrical hearing loss

- Sudden hearing loss (72h or less)

- Otalgia + otorrhoea in immunocompromised person with no response in 72h

Conduction and hearing loss

Tuning fork tests

- Compare air conduction (AC) with bone conduction (BC) and difference between ears

- Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) - cochlear or VIII nerve damage: BC>AC

- Conductive hearing loss (CHL) - middle/outer ear dysfunction

- Mixed hearing loss (MHL) combination of both

Rinne

- Rinne: ear canal (AC) vs mastoid (BC)

- Positive: louder via AC – SNLH or normal hearing

- Negative: louder via BC – CHL

Weber

- Weber: tuning fork mid-forehead

- Lateralises to ear with loss: CHL – BC better

- Lateralises to hear without loss: SNHL or mixed hearing loss (MHL) as best cochlea detecting sounds

- Normal hearing: midline

Next steps

Referral guidance: immediate

- Unexplained sudden onset (over <72h) hearing loss within past 30 days

- Unilateral loss with focal neurology

- Hearing loss with head injurybor severe ear infection

Referral guidance - urgent

- Unexplained sudden onset (over <72h) hearing loss over 30 days ago

- Unexplained rapid loss (4-90 days)

Communication tips

- Get attention before speaking

- Make face and lips visible

- Make facial expressions and gestures

- Avoid background noise

- Don't look away when talking

- Repeat sentence once if needed, after then rephrase

- Write down important facts

- Allow enough time for consultation

Common symptoms table – How patient may present

Otitis Media and Otitis Media with Effusion:

|

Symptom |

Otitis Media (OM) |

Otitis Media with Effusion* (OME) |

|---|---|---|

|

Ear Pain |

Often present, can be severe |

Usually absent or mild |

|

Ear Discharge |

May have pus or fluid draining from ear |

Typically no discharge |

|

Hearing Loss |

Temporary due to fluid build-up |

Mild to moderate, may persist. Muffled hearing (Most common). |

|

Fever |

Often present, especially in children |

Rarely present |

|

Ear Fullness or Pressure |

Common |

Common |

|

Redness of the Eardrum |

Possible |

Uncommon |

|

Bulging of the Eardrum |

Possible |

Uncommon |

|

Tugging or pulling at the ear (in children) |

Common |

Uncommon |

|

Upper Respiratory Infection Symptoms |

May be present |

Typically absent |

*otitis media with effusion is also known as glue ear

It's important to note that these symptoms can vary in severity and presentation from person to person. With glue ear, children have difficulty understanding speech, especially in noisy environments and can lead to speech and language delays in children.

More information on Otitis Media and Otitis Media with Effusion.

Acute and chronic otitis externa:

|

Symptoms |

Typical Symptoms of Acute Otitis Externa |

Typical Symptoms of Chronic Otitis Externa |

|---|---|---|

|

Ear Itch |

Present |

Constant itch in the ear |

|

Ear Discharge |

Present |

N/A |

|

Ear Pain |

Present |

Mild discomfort or pain |

|

Tenderness of Tragus/Pinna |

Present |

Present |

|

Jaw Pain |

Possible |

N/A |

More information on Acute and chronic otitis externa

Tinnitus is a term to describe a symptom of the ear which can present as:

- Buzzing

- Roaring

- Clicking

- Hissing

- Whistling

- Whooshing

The sounds you hear can be constant or intermittent, and they can vary in volume from barely noticeable to quite loud. For some people, tinnitus can be very bothersome and can interfere with their ability to sleep, concentrate, or relax. For more information can refer to the tinnitus page.

More information on Tinnitus assessment and management

Dizziness vs Vertigo

Dizziness is a general term for various sensations of imbalance, unsteadiness, light-headedness or feeling faint, vertigo specifically refers to the sensation of spinning or movement (often described as “the room is spinning around”), often associated with problems in the inner ear or vestibular system.

Table differentiating the symptoms of BPPV, meniere’s disease, vestibular neuritis and vestibular labyrinthitis.

| Sympton | Vestibular Neuritis |

Vestibular Labyrinthitis | BPPV | Ménière's Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertigo | Sudden onset of vertigo | Sudden onset of vertigo | Brief episodes triggered by head movement | Severe and prolonged vertigo attacks |

| Duration of Vertigo Attacks | Usually resolves in days | Can last days to weeks | Typically brief (seconds to minutes) | Can last hours to days |

| Recurrence of Vertigo | Typically resolves after initial episode | May recur with future infections | Episodes may recur intermittently | Recurrent attacks with remissions |

| Speed/Onset/Timing of Vertigo | Sudden onset, usually resolves within days | Sudden onset, can last days to weeks | Sudden onset with specific head movements which can last seconds to minutes | Sudden onset or gradual worsening, can last hours to days |

| Trigger Factors | Viral infection, preceding illness | Viral infection, preceding illness | Head movements, changing position | Stress, dietary factors |

| Nausea | Variable; may accompany vertigo | Common during vertigo episodes | Common during vertigo episodes | Common during vertigo episodes |

| Vomiting | Less common | May occur during severe episodes | May occur during severe episodes | May occur during severe attacks |

| Hearing Loss | None or minimal | None or minimal | Typically none | Fluctuating, progressive |

| Tinnitus | May occur | May occur | Rarely present | Common, often with fluctuation |

| Ear Fullness or Pressure | May occur | Common | Rarely present | Common |

More information on Balance differentials, BPPV or Meniere’s Disease.

Common Red Flags and Referral Guidelines Timeline

NICE guidelines: Hearing Loss in Adults was updated in September 2019. The recommendations on the timeliness of referrals for patients with a hearing loss to Ear Nose Throat (ENT) specialist, emergency department or audiovestibular medicine service are based on the guidance from the British Academy of Audiology and expert opinion in review articles.

Red Flags

- Asymmetrical or Unilateral Hearing Loss - Age related hearing loss should be symmetrical. If an individual is reporting hearing loss that is greater in one ear than the other, then further investigation is required.

- Sudden hearing loss (over >72 hours or less) within the past 30 days is considered a medical emergency. Individuals should be seen within 24 hours by an ear, nose and throat service or an emergency department.

- If the hearing loss worsened rapidly (over a period of four to 90 days), refer urgently (to be seen within two weeks) to an ear, nose and throat or audiovestibular medicine service.

- For otalgia (earache) with otorrhoea (discharge from the ear) that has not responded to treatment within 72 hours and the individual is immunocompromised, refer to an ear, nose and throat service to be seen immediately within 24 hours.

- Persisting middle ear effusion in patients of Chinese or Southeast Asian origin.

- Fluctuating hearing loss.

- Hyperacusis (intolerance to everyday sounds that causes significant distress and affects a person’s day-to-day activities).

- Persistent tinnitus that is unilateral, pulsatile, has significantly changes in nature or is causing distress.

The guideline covers timelines of when to:

- Sudden onset (over three days or less) unilateral or bilateral hearing loss which has occurred within the past 30 days and cannot be explained by external or middle ear causes

- Unilateral hearing loss associated with focal neurology

- Hearing loss associated with head or neck injury

- Hearing loss associated with severe infection, for example, necrotising otitis externa

- Sudden onset (over three days or less) unilateral or bilateral hearing loss which developed more than 30 days ago and cannot be explained by external or middle ear causes

- Rapidly progressive hearing loss (over a period of four to 90 days) which cannot be explained by external or middle ear causes.

- Suspected head and neck malignancy — refer using a two-week cancer pathway

- Unilateral or asymmetric gradual onset hearing loss as their main symptom

- Fluctuating hearing loss that is not associated with an upper respiratory tract infection

- Hearing loss associated with hyperacusis

- Hearing loss associated with persistent tinnitus which is unilateral, pulsatile, significantly changed or causing distress

- Hearing loss associated with persistent or recurrent vertigo

- Hearing loss that is not age related

- Diagnosed dementia or mild cognitive impairment

- Suspected dementia

- Diagnosed learning disability

If unsure if to refer to ENT or AVM or Audiologists, please refer to the referral pathways section of the toolkit.

Additional information and further reading:

- NICE guidelines - Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management - Assessment and referral

- NICE guidelines- Hearing loss in adults: assessment and amangement - When should I refer a person with hearing loss to secondary care?

- NICE guidelines NG98 Full document - Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management - Immediate, urgent, and routine referral - see page 55

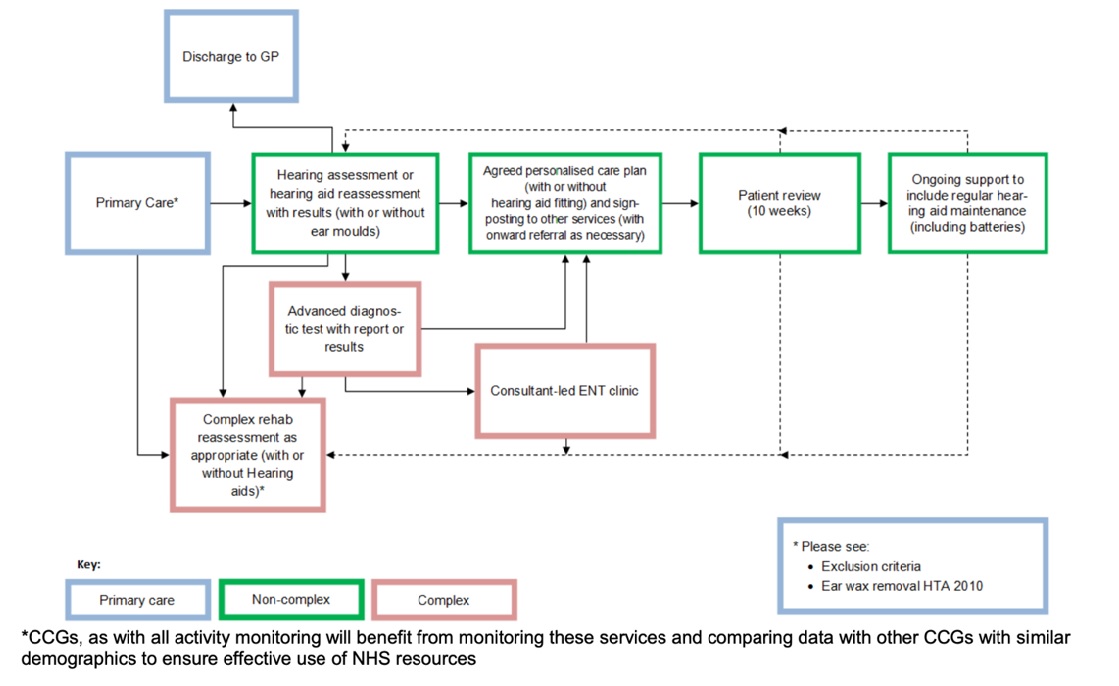

Referral Pathways

Regional variations exist, please check local services.

Adult Rehabilitation (Audiology)

- Some audiology services are now taking direct referrals from age 16, but most take referrals from age 18 onwards or from age 50 onwards. Please check with local services for age criteria.

- A hearing assessment is undertaken and further management in the form of hearing aid provision or assistive listening devices

- Patients are followed-up and are routinely reassessed at the discretion of the local audiology service. Please refer to sections 1.5, 1.6, 1.7 in the NICE guidance NG98 for further details on assessment and management undertaken in audiology services.

- If an exclusion criterion is met during the patient’s assessment in audiology they will be referred onwards to the local Ear, Nose, Throat (ENT) Department, audiovestibular medicine (AVM) service, or GP for further investigation and management.

- The British Academy of Audiology has produced this 'Guidance for Primary Care: Direct Referral of Adults with Hearing Difficulty to Audiology Services' (PDF), which contains further details and explanation of the exclusion criteria.

ENT/AVM

- If patient meets any of the exclusion criteria outlined in the guidance, please refer onwards to the local ENT department, AVM, or specialist audiology practitioner depending on local services/protocols.

- Refer to AVM for complex hearing and/or balance disorders (i.e. central pathologies).

- Refer to ENT for conditions that may require surgical management (i.e. otosclerosis, otitis media with effusion, cholesteatoma etc

Audiology Led Clinics (ALC)

- Please check your local area if this service exists.

- It is a direct access clinic for adults aged 18 to 75 with non-complex: tinnitus and/or hearing loss or balance problems (peripheral, inner ear disorders i.e. BPPV, vestibular neuritis etc.) Patients are seen by audiologists with an extended scope of practice and expertise beyond routine hearing assessments.

Hearing Therapy/Clinical Psychology

- For patients who have had all necessary medical investigations completed by ENT/AVM, GP or audiologists

- Refer complex patients for counselling, habilitation and further management of tinnitus, hyperacusis, auditory processing disorder management, and mindfulness

Auditory Implant Services

- Please refer adults with severe to profound deafness for a cochlear implant assessment if they do not receive adequate benefit from acoustic hearing aids

- Please refer to NICE guidance for further details and criteria

Sensory Services

- Sensory services is under adult social services and is for those who are visually impaired, deaf or hard of hearing, or dual sensory impairments. The team provides specialist equipment to aid mobility, communication and daily living in response to assessed needs, for example, vibrating alarms, flashing smoke alarms, telecoil systems and others

- Please check with your local council.

Information and Support for Patients and Carers

- Association of Sign Language interpreters (ASLI)

- Association of LipSpeakers (ALS)

- Association of Verbatim Speech-to-text Reporters (AVSTTR)

- BID Services

- British Acoustic Neuroma Association (BANA)

- British Deaf Association (BDA)

- British Tinnitus Association (BTA)

- C2Hear

- Delta Deaf Education through listening and talking

- Deaf Blind UK

- DeafHope – Domestic Abuse Help

- The Deaf Health Charity: Domestic Abuse

- deafPLUS

- European Union of the Deaf (EUD)

- Hearing Dogs for Deaf People

- Hearing Link

- INTERPRETERNOW

- Ménière's Society

- National Association of Deafened People (NADP)

- National Cochlear Implant Users Association

- National Deaf Children’s Society (NDCS)

- Royal Association for Deaf People (RAD)

- Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID)

- Sense

- Shout - Crisis Text Line

- Sign Health

- United Kingdom Council on Deafness (UKCoD)

- UK Deaf Sport

- World Federation of the Deaf (WFD)

Psychosocial Effects of Hearing Loss

Hearing loss can have a major impact on daily functioning and quality of life of a person. It can affect communication, their occupation, social interactions leading to loneliness and affect their families. Research shows that hearing loss doubles the risk of developing depression and increases the risk of anxiety and other mental health issues, while many sufferers remain undiagnosed or untreated. It also suggests that the use of hearing aids reduces these risks and is cost effective. GPs should routinely screen for depression during consultations of patients with hearing loss.

Research around the experience of people with hearing loss and employment found that: 68% of people with hearing loss felt isolated at work because of their hearing loss and 41% had retired early due to the impact of their hearing loss and struggles with communication at work.1

References

Hearing Loss and the risk of developing dementia

A study in the Lancet found that hearing loss is a major risk factor of cognitive decline resulting in dementia. It is estimated that at least £28 million per year could be saved in England by properly managing hearing loss in people with dementia.1

Evidence found that mild hearing loss doubles the risk of developing dementia, with moderate hearing loss leading to three times the risk, and severe hearing loss five times the risk. Hearing loss can be misdiagnosed as dementia or make the symptoms of dementia appear worse. Although dementia is diagnosed in later life, changes in the brain usually start developing many years before. The study looked at the benefits of building a "cognitive reserve", meaning that if the brain’s networks were strengthened, it could continue to function in later life regardless of the damage.2,3

A study by the University of Exeter and King’s College London also found that people who wore hearing aids for age-related hearing problems maintained better cognitive functions than those with similar hearing who did not use them. Those who wore them had brains that performed as if they were, on average, eight years younger. NICE Guidelines state that hearing aids are the primary management option for permanent hearing loss.4

Individuals with memory complaints often present at their GP and assessment of hearing is now recommended as a first step in its investigation. The communication difficulties and misunderstanding caused by hearing loss commonly mimic memory loss. Screening for hearing loss in high-risk populations such as those attending memory clinics or people older in age has been suggested to ensuring hearing loss is identified and managed in a timely manner to facilitate healthy aging. It is accepted that earlier provision of hearing aids leads to better utilisation and concordance. Treating hearing loss in people with dementia also has the potential to reduce the severity of dementia related behaviours such as confusion and simplify communication with families and carers.

At Imperial College London, the Clinical Lead for Adult Audiology has conducted research around the relationship between hearing loss and dementia. A sound clip has been developed (available on the powerpoint on the GPVTS teaching and curriculum section). It demonstrates to clinicians administering cognitive assessments how a common age-related hearing loss can completely distort speech and negatively affect scores on these cognitive assessments. This is particularly in cases that require the patient to repeat back a sentence they have heard.

References:

- Hearing Link: Facts about deafness and hearing loss

- RNID: 'Why and how are dementia and hearing loss linked? Our Audiologist explains the latest research'

- The Hearing Review: Nine Risk Factors Associated with Dementia

- NICE, Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management. 2018, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

Interpretation of Investigations

Please note an audiologist/AVM/ENT will send a summary/copy of the basic investigations below to you after the assessment has taken place.

Otoscopy

The British Society of Audiology produced a detailed procedure for ear examination.

Tuning Forks

Provides preliminary diagnostic information.

Rinne

- Comparison of air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC) sensitivity

- Tuning fork is alternated between entrance of ear canal and mastoid process

- Rinne Positive: Tuning fork is louder via AC= sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL)

- Rinne Negative: Tuning fork is louder on mastoid= conductive hearing loss (CHL)

Weber

- Test of lateralisation and therefore may be used for patients who report unilateral hearing loss.

- The tuning fork is placed midline on the patients’ forehead.

- If sound lateralises to ear with loss= CHL as the improved BC is due to the occlusion effect.

- If soundlateralises to ear without loss=SNHL or mixed hearing loss (MHL) as the best cochlea is detecting the signal. In normal hearing= midline

Types of hearing loss

- CHL is a result of dysfunction in the middle or outer ear (BC >AC)

- SNHL is a result of cochlea damage (sensory) and/or neural (8th nerve) (BC = AC)

- Mixed hearing loss is a combination of dysfunction in middle/outer ear and cochlea/8th nerve (A certain amount of AC and BC loss)

- Central hearing loss refers to everything in the auditory cortex (Brain) whereas peripheral hearing loss is the result of everything before the brain (outer, middle, inner ear)

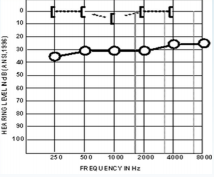

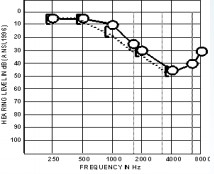

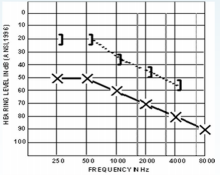

Interpreting a Pure-tone Audiogram (PTA)

- An audiogram is a plot of frequency in Hertz (Hz) against intensity measured in decibels hearing level (dB HL). The frequency range for a PTA is 250 Hz to 8000Hz as this range of frequencies is similar to the range important for speech understanding.

- The intensity ranges from -10dB HL to 120dB HL. Thresholds (lowest acoustic intensity perceived at a given frequency) for both the right and left ear are plotted based on the frequency. Refer to image below.

- Masked AC/BC thresholds are an accurate assessment of the test ear.

- Further interpretation and explanations on Pure-tone Audiogram are available on the BSA website:

| Descriptor | Average hearing threshold levels (dB HL) |

|---|---|

| Normal Hearing | < 20 |

| Mild hearing loss | 21 - 40 |

| Moderate hearing loss | 41 - 70 |

| Severe hearing loss | 71 - 95 |

| Profound hearing loss | > 95 |

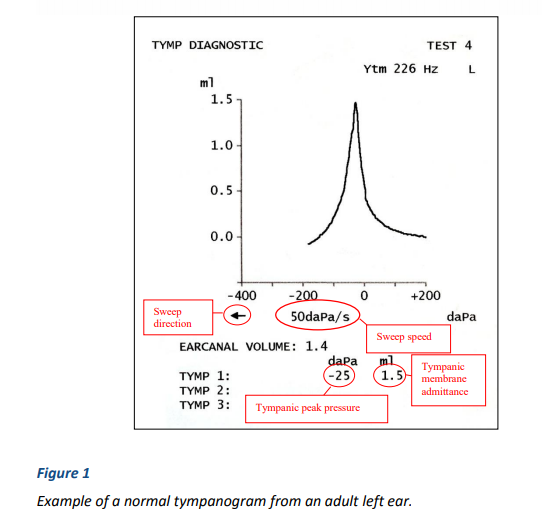

Interpreting a Tympanogram

- Tympanogram is graphic display of tympanic membrane compliance (ml or cm3) as a function of pressure changes in the external auditory meatus. See figure 1.

- Tympanometry is sensitive to middle ear effusion, cholesteatoma, ossicular adhesions, and space occupying lesions in contact with the eardrum, ossicular discontinuity, perforations and ear canal occlusions.

- The shape of the tympanogram should also be described and simple descriptions such as ‘normal’, ‘rounded’, ‘flat’, ‘wide’ or ‘W-shaped’.

- The BSA has further interpretation and explanations on Tympanometry.

Examples of Types of Hearing Loss

Conductive Hearing Loss

- An audiogram illustrating a mild conductive hearing loss in the right ear. The air-conduction thresholds for the right ear are shown as O’s and the masked, bone-conduction thresholds are shown as brackets.

- Examples of a conductive hearing loss included a perforated tympanic membrane, and otitis media with effusion etc.

Sensorineural Hearing Loss

- An audiogram illustrating a mild-moderate, high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss in the right ear.

- Examples of a SNHL includes presbycusis, an acoustic neuroma, Meniere’s disease, and noise-induced hearing loss etc.

Mixed hearing loss

- An audiogram illustrating a moderate-to-severe, mixed hearing loss in the left ear. Both the air-conduction thresholds (X’s) and the bone-conduction thresholds (brackets) indicate hearing loss.

- Examples of mixed hearing loss includes otosclerosis, a SNHL with a perforation/otitis media with effusion.

References:

Stanley A. Gelfand (2011). Essentials of Audiology, 3rd Edition. Thieme, New York NY 2011Balance differentials

| Cause | Description | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) |

Brief episodes of dizziness triggered by specific head movements, such as rolling over in bed or looking up. Inner ear debris affecting balance organs is often the cause. | Management typically involves Canalith repositioning manoeuvres (e.g., Epley manoeuvre) to move the inner ear debris out of the semicircular canal. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises may also be provided by the GP or referral to an audiologist. |

| Meniere's Disease | Recurrent episodes of vertigo, hearing loss, tinnitus, and a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear. Believed to be due to abnormal fluid build-up in the inner ear. | Medications to control acute symptoms (e.g. prochlorperazine, cinnarizine), vestibular rehabilitation exercises. For recurrent attacks trial betahistine, for a length of time in accordance to patient’s response. |

| Vestibular Neuritis | Sudden onset of severe vertigo, often with nausea and vomiting, without hearing loss. Caused by inflammation of the vestibular nerve, typically due to a viral infection. | Management focuses on symptom relief with medications for nausea and vestibular suppressants (e.g., antihistamines - prochlorperazine, cinnarizine) during the acute phase. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises may be beneficial in the recovery phase to promote compensation. |

| Labyrinthitis | Similar to vestibular neuritis but with additional symptoms of hearing loss and possibly tinnitus. Caused by inflammation of the inner ear structures, often due to infection. | Management is similar to vestibular neuritis and may include medications for symptom relief, such as vestibular suppressants and corticosteroids during the acute phase, as well as vestibular rehabilitation exercises for long-term recovery and compensation. |

| Migraine-Associated Vertigo (MAV) | Vertigo or dizziness associated with migraines. Often accompanied by headache, sensitivity to light and sound, and nausea. Believed to be related to abnormal processing of sensory information in the brain. | Management involves migraine-specific treatments such as medications (e.g., triptans, antiemetics), lifestyle modifications (e.g., stress management, regular sleep patterns), and avoidance of triggers known to precipitate migraines. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy may also be helpful. |

| Orthostatic Hypotension | Dizziness or light-headedness upon standing up, often due to a drop in blood pressure. Can be caused by dehydration, medications, or underlying medical conditions affecting the autonomic nervous system. | Management includes lifestyle modifications (e.g., increasing fluid and salt intake, avoiding alcohol), wearing compression stockings, adjusting medications that may contribute to low blood pressure, and implementing counter-pressure manoeuvres (e.g., tensing leg muscles when standing) to improve blood flow. |

| Motion Sickness | Dizziness, nausea, and vomiting triggered by motion, such as travel in cars, boats, or airplanes. Caused by conflicting sensory signals to the brain regarding motion and position | Management strategies include medications (e.g., antihistamines, anticholinergics), acclimatization techniques (gradual exposure to motion), behavioural therapies (e.g., focusing on a fixed point), and using supportive measures like wearing wristbands or patches. |

| Anxiety or Panic Attacks | Dizziness or light-headedness often accompanied by palpitations, sweating, and feelings of impending doom. Typically related to acute stress or panic disorder. | Management involves cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), relaxation techniques (e.g., deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation), medication (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines), and addressing underlying stressors or triggers through therapy or lifestyle changes. |

| Hyperventilation Syndrome | Dizziness, light-headedness, and tingling sensations in the extremities due to rapid or shallow breathing, leading to changes in blood chemistry. Often associated with anxiety or panic attacks. | Management focuses on addressing breathing patterns through techniques such as paced breathing, rebreathing into a paper bag (for acute episodes), relaxation exercises, and CBT to modify dysfunctional breathing patterns and reduce anxiety. |

| Medication Side Effects | Dizziness as a side effect of certain medications, including blood pressure medications, sedatives, antidepressants, and antipsychotics, among others. | Management involves reviewing and adjusting medications under the guidance of a healthcare professional. Depending on the medication and severity of symptoms, alternatives may be considered, dosage adjustments made, or additional medications prescribed to alleviate dizziness. |

| Neurological Disorders | Dizziness can be a symptom of various neurological conditions, including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, and stroke. | Management depends on the specific neurological disorder and may involve medications to manage symptoms, physical therapy for balance and coordination, lifestyle modifications, and in some cases, surgical interventions or other specialized treatments targeted at the underlying condition. |

| Cardiovascular Disorders | Conditions affecting blood flow to the brain, such as carotid artery stenosis, arrhythmias, or transient ischemic attacks (mini-strokes), can cause dizziness. | Management varies based on the underlying cardiovascular disorder and may include medications to control blood pressure or heart rate, lifestyle modifications (e.g., diet, exercise), surgical interventions (e.g., carotid endarterectomy), and addressing any contributing factors such as smoking or high cholesterol. |

| Inner Ear Disorders (Other than BPPV) | Conditions affecting the inner ear, such as vestibular migraine, Meniere's disease, and vestibular neuritis/labyrinthitis, can lead to recurrent episodes of vertigo or chronic dizziness. | Management depends on the specific inner ear disorder but may include a combination of medications (e.g., diuretics, vestibular suppressants), lifestyle modifications, vestibular rehabilitation exercises, and in some cases, surgical interventions or other specialized treatments targeted at the underlying cause. |

| Cervical Vertigo | Dizziness or imbalance triggered by certain head movements or neck positions, often due to dysfunction or injury in the cervical spine (neck). | Management may include physical therapy for cervical spine stabilization and strengthening exercises, postural training, ergonomic adjustments, and pain management strategies (e.g., medications, heat therapy) to address underlying cervical spine issues contributing to vertigo. |

| Hypoglycaemia | Low blood sugar levels can cause dizziness, weakness, and confusion. It is often associated with diabetes but can occur in individuals without diabetes as well. | Management involves addressing the underlying cause of hypoglycaemia, such as adjusting diabetes medications or insulin doses, consuming fast-acting carbohydrates to raise blood sugar levels (e.g., glucose tablets, fruit juice), and implementing dietary changes and monitoring to prevent future episodes. |

| Dehydration | Inadequate fluid intake leading to dehydration can cause dizziness, weakness, and confusion. | Management focuses on rehydration through oral fluids or, in severe cases, intravenous. |

Tinnitus: assessment and management

NICE guideline [NG155] Published: 11 March 2020

Introduction

Tinnitus, the perception of sound in the absence of an external source, affects up to 1 in 5 people in the UK and significantly burdens healthcare resources.

Remember tinnitus is a symptom not a disease.

Prevention: Noise Exposure: 60/60 Rule

60/60 rule, never turn your volume up past 60%, and only listen to music with earbuds for a maximum of sixty minutes per day.

The rise in tinnitus numbers is due to the increasing and aging UK population. However, a recent study from Statistics Canada revealed that 80% of adults aged 19 to 29 reported using headphones or earbuds connected to audio devices in the past year had rates of tinnitus over one third higher than for older adults.

Diagnoses not to miss

- Vestibular schwannoma: Benign tumour on 8th cranial nerve/cerebropontine angle. Unilateral/asymmetrical sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, facial weakness/numbness

- Stroke: Patients presenting with the classic stroke symptoms may also have sudden onset tinnitus and/or vertigo and/or hearing loss if the arterial supply to the labyrinth is affected eg. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery infarcts

- Ménière’s disease (endolymphatic hydrops): Vertigo (lasting 20 mins - hours), tinnitus, fluctuating/sensorineural hearing loss, aural fullness

- Cholesteatoma: Epidermal skin from the ear canal or outside surface of the eardrum, does not belong in the middle ear. May present with otorrhoea, mixed or conductive hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, facial nerve palsy

- Sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a rapid loss of hearing that occurs suddenly or over a period of up to 72 hours. May present with tinnitus and vertigo

- Glomus jugulare tumour: Rare slow-growing, vascular tumours of a group called paragangliomas. The most common symptoms are deafness and pulsatile tinnitus. There may be associated vertigo

Examination

- Otoscopic examination

- Check cranial nerves for focal neurological signs

- Rinne and Weber tests

Rinne test

- Comparison of air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC) sensitivity

- Tuning fork is alternated between entrance of ear canal and mastoid process

- Rinne Positive: Tuning fork is louder via AC = sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL)

- Rinne Negative: Tuning fork is louder on mastoid = conductive hearing loss (CHL)

Weber test

- Test of lateralisation and therefore may be used for patients who report unilateral hearing loss.

- The tuning fork is placed midline on the patients’ forehead.

- If sound lateralises to ear with loss = conductive hearing loss as the improved bone conduction is due to the occlusion effect.

- If sound lateralises to ear without loss = sensorineural hearing loss or mixed hearing loss (MHL) as the best cochlea is detecting the signal. In normal hearing= midline.

Whisper test

A simple and accurate test for detecting hearing impairment:

- The examiner stands at arm's length (0.6 m) behind the seated patient (to prevent lip-reading) and whispers a combination of three numbers and letters (for example, 4-K-2) and then asks the patient to repeat the sequence.

- The examiner should quietly exhale before whispering to ensure as quiet a voice as possible.

- If the patient responds incorrectly, the test is repeated using a different number/letter combination. The patient is considered to have passed the screening test if they repeat at least three out of a possible six numbers or letters correctly (i.e 50% correct).

- Each ear is tested individually, starting with the ear with better hearing. During testing, the non-test ear is masked by gently occluding the auditory canal with a finger and rubbing the tragus in a circular motion.

- The other ear is assessed similarly with a different combination of numbers and letters.

- Consider blood tests to rule out potential causes of tinnitus e.g. diabetes and thyroid tests.

- Offer audiometry to anyone who reports hearing loss or fails the whisper test, has unilateral tinnitus or tinnitus of more than 6 months duration.

- Explore effect on social wellbeing, QOL, daily activities (eg. via Tinnitus Functional Index questionnaire).

When to refer and timescales

| Referrals to ENT (red flags) | Referrals for support (usually CBT) |

|---|---|

| Unilateral tinnitus Pulsatile tinnitus Focal neurological abnormality (eg possible stroke presentation which would need acute admission) Asymmetric hearing loss |

Significant distress Impact on mental health |

Refer immediately for potential admission:

- To a crisis mental health management team for assessment for people who have tinnitus associated with a high risk of suicide

- Tinnitus associated with sudden onset of significant neurological symptoms or signs (for example, facial weakness)

- Tinnitus associated with acute uncontrolled vestibular symptoms (for example, vertigo)

- Tinnitus associated with suspected stroke symptoms

Refer to ENT for tinnitus assessment and management if:

- Tinnitus bothers them despite having received tinnitus support at first point of contact with a healthcare professional

- Persistent objective tinnitus

- Tinnitus associated with unilateral or asymmetric hearing loss

Consider referring to ENT for tinnitus assessment and management if:

- Patients have persistent pulsatile tinnitus

- Patients have persistent unilateral tinnitus

Patients who do not meet the criteria for ENT referrals or referrals for support can be managed in primary care.

1. Education

Many who present are concerned that tinnitus may be a sign of a more serious condition, or result in progressive hearing loss or deterioration. Therefore education is key:

- E.g. for those with mild symptoms, offer an explanation and an information leaflet

National support groups and resources to signpost patients to (see below for links):

- British Tinnitus Association

- Royal National Institute of Deaf People (RNID)

2. Medical Management

- There are no perfect studies looking at the treatment of tinnitus – they all have short periods of follow-up, there are no standardised assessments and risk of bias is high

- There are currently no medications, supplements or herbal remedies that have any evidence to significantly reduce the severity of tinnitus

- If there is co-existing psychological problems/insomnia, managing this with medication (in addition to other strategies) may reduce the impact of tinnitus on quality of life

- NICE advises not to offer betahistine to people with tinnitus as evidence suggests it does not improve tinnitus symptoms and has side effects notably in the gastrointestinal tract

3. Acoustic Stimulation

Possible strategies for those who do not require hearing aids include:

- Broadband noise generators (which are also available via tinnitus apps)

- Music

4. Psychological Treatments

There are two aims of psychological treatment:

- To decrease the negative effect of tinnitus on the individual

- To treat associated mental health problems, e.g. anxiety and depression

Psychological techniques you can consider signposting to or recommending:

- Mindfulness

- Relaxation training, because stress and tension impair the individual's ability to cope with tinnitus e.g. breathing exercises and progressive muscle relaxation

- Attention refocusing

If a person does not benefit from the first psychological intervention or declines an intervention, then consider a stepped approach and referral to secondary care.

Psychological therapies for people with tinnitus-related distress

NICE recommends considering a stepped approach in the following order:

- Digital tinnitus-related cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- Group-based tinnitus related psychological interventions including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), or CBT

- Individual tinnitus related CBT

References

- British Society of Audiology - Tinnitus in Children Practice Guidance.2015

- British Tinnitus Association - What is tinnitus?

- GP Online - Red flag symptoms: Tinnitus. 2018

- Hearing Link - What is tinnitus?

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence - Suspected neurological conditions: recognition and referral. NICE guideline 127. 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence - Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management. NICE guideline 98. 2018.

- NHS England - Joint Assessment Needs Assessment Guidance

- Statistics Canada - Tinnitus in Canada

Useful resources

Resources from the British Tinnitus Association:

- Web chat (available via the website)

- Take on Tinnitus

- Helpline – 0800 018 0527

Resources from Action on Hearing Loss:

- Tinnitus information line 0808 808 6666

- Email: tinnitushelpline@hearingloss.org.uk

- Textphone - 0808 808 9000

You may find it helpful to direct people to the BTA online shop to purchase additional equipment to help manage their tinnitus, such as sleep phones or pillow speakers:

Specific resources for telephone/skype consultations, managing tinnitus whilst socially distancing:

- BTA are running online support groups, for more information: colette@tinnitus.org.uk

- BTAinformation on Social distancing and managing tinnitus

- Tinnitus Apps can be very helpful and BTA have compiled a list of different types ofapps

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

What is BPPV?

BPPV is the most common inner ear disorder causing vertigo, a sensation of spinning or dizziness. It occurs due to displaced otoconia (tiny calcium carbonate crystals) within the inner ear canals, triggering abnormal signals sent to the brain regarding head position.

Clinical presentation

- Brief episodes of vertigo (seconds to minutes) triggered by specific head movements (e.g., lying down, rolling over)

- Possible nausea and vomiting, imbalance or light-headedness, and nystagmus during vertigo episodes

- Hearing is NOT affected and tinnitus is not a feature

BBPV differentials

Please also refer to the balance differentials document for more information.

These are some of the main differentials to consider when evaluating a patient with symptoms suggestive of BPPV. It's essential to conduct a thorough history, physical examination, and possibly diagnostic tests to accurately diagnose the underlying cause of vertigo. Differentials of BBPV include: meniere’s disease, vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, central vertigo, vestibular migraine to name a few.

Assessment

Detailed history focusing on vertigo characteristics and triggers.

Examination is likely to be normal at rest in a sitting position.

Physical examination (full ENT, cardiovascular, neurological examinations) to exclude other causes.

Imaging is not required to diagnose BPPV, it is to rule out other causes.

(Be cautious if considering the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre if the person has a neck or back problem, or cardiovascular problems such as carotid sinus syncope, as it involves turning the head and extending the neck)

To carry out the manoeuvre:

- Advise the person that they may experience transient vertigo during the procedure.

- Ask the person to keep their eyes open throughout the manoeuvre and to look straight ahead.

- Ask the person to sit upright on the couch with their head turned 45 degrees to one side.

- From this position, lie the person down rapidly (over 2 seconds), supporting their head and neck, until their head is extended 20-30 degrees over the end of the couch with the chin pointing slightly upwards and the test ear downwards. Support the head to maintain this position for at least 30 seconds.

- Observe their eyes closely for up to 30 seconds for the development of nystagmus. If nystagmus is present, maintain the position for its duration (maximum 2 minutes if persistent) and note its duration, type, direction, and latency.

- Record duration, severity, and latency of any vertigo.

- Support the head in position and slowly sit the person up.

- Repeat with the head rotated 45 degrees to the other side.

Referral for GPs (red flags) to ENT

- Admit the person to hospital if they have severe nausea and vomiting and are unable to tolerate oral fluids.

- Physical limitations affect the safety or practicality of carrying out canalith repositioning procedures in primary care.

- A canalith repositioning procedure (for example the Epley manoeuvre) has been performed and repeated, and symptoms are still present.

- Symptoms or signs are atypical.

- Symptoms and signs have not resolved in 4 weeks

- Uncontrolled vertigo despite appropriate CRM attempts.

- Suspected central nervous system involvement (e.g. stroke, tumour).

Management

- Discuss the option of watchful waiting to see whether symptoms settle without treatment over a few weeks.

- Consider suggesting Brandt-Daroff exercises which the person can do at home, particularly if the Epley manoeuvre cannot be performed immediately or is inappropriate. These exercises can improve balance and reduce dizziness after successful canalith repositioning manoeuvres (CRMs):

- Sit on the edge of a bed or couch with the eyes closed.

- Quickly lie down sideways on one side with their eyes closed so that they are lying on their side with the lateral aspect of their occiput resting on the bed, with the head positioned as if they are looking towards the ceiling (rotated 45 degrees upwards)

- Rest in this position for at least 30 seconds, until any vertigo subsides.

- Keeping the eyes closed, sit upright again, and remain in this position for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

- Repeat the sequence 3–4 times until they are symptom free.

- Repeat 3–4 times a day until there have been 2 consecutive days without symptoms.

- CRMs are highly effective exercises performed by a healthcare professional to reposition the displaced otoconia. Common CRMs include Epley maneuver and Semont maneuver.

(Be cautious performing the Epley manoeuvre if the person has neck or back problems, unstable cardiac disease, suspected vertebrobasilar disease, carotid stenosis, or morbid obesity)

- Advise the person that they will experience transient vertigo during the manoeuvre.

- Stand at the side or behind the person to guide head movements. Maintain each head position for at least 30 seconds. If vertigo continues, wait until it has subsided.

- Ideally, movements should be rapid, within 1 second, but this is often not possible, particularly in older people. Expert opinion suggests that the procedure can be effective if movements are carried out slowly.

- Start with the person sitting upright with their head turned 45 degrees to the affected side, then lie them back (with their head still turned 45 degrees) until the head is dependent 30 degrees over the edge of the couch (as if performing the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre). Wait for at least 30 seconds. Then:

- With the face upwards, but still tilted backwards by 30 degrees, rotate the head through 90 degrees to the opposite side.

- Hold the head in this position for about 20 seconds and ask the person to roll onto the same side as they are facing.

- Rotate the person's head so that they are facing obliquely downward with their nose 45 degrees below the horizontal

- Sit the person up sideways while the head remains rotated and tilted to the side.

- Rotate the head to the central position and move the chin downwards by 45 degrees.

- There is usually no need to advise the person of any positional restrictions after the procedure has been performed.

- Medications: Not typically curative, but short-term use of antiemetics or vestibulosuppressants (suppress inner ear activity) may be considered for symptom relief e.g. prochlorperazine, cinnarizine.

References

Paediatric Hearing - Foreign Body

Small children may put objects such as pips, beads and paper clips in their ears. Adults may get foreign bodies like toothpicks stuck in an attempt to use them to clean wax out of their ears. Organic foreign bodies are more likely to cause infection.

Keys to successful foreign body removal are adequate visualisation, appropriate equipment, a cooperative patient, and a skilled physician1

Several points relating to management are noteworthy:

- Removal of the foreign body by syringing is not usually successful.

- If removal seems impossibly difficult then refer the job to someone skilled in this area - i.e. ENT

- An uncooperative patient may necessitate resorting to removal under general anaesthetic.

- After removal the tympanic membrane must be checked - there may be a perforation which must be treated.

The following should be avoided2:

- Use of a rigid instrument to remove a foreign body from an uncooperative patient's ear

- Removal of a large insect without killing it first

- Irrigating a tightly wedged seed from an ear canal. Water causes the seed to swell.

- Removal of a large or hard object with bayonet, alligator or similar forceps which may push them further into the canal

Indications for referral include1:

- lack of expertise of clinician in removal of foreign body - the first attempt at removal has the greatest chance of success

- need for sedation

- trauma to ear canal or tympanic membrane

- foreign body is non-graspable

- foreign body touching the tympanic membrane

- tightly wedged foreign body

- sharp-edged foreign body

- unsuccessful removal attempts

References

- Heim SW et al. Foreign bodies in the ear, nose, and throat. Am Fam Physician 2007;76:1185-9.

- Foreign Body in Ear. National Center For Emergency Medicine Informatics 2007

Paediatric Hearing - Otitis Externa (Swimmers Ear)

What is Otitis Externa (Swimmer's Ear)?

Otitis Externa, also known as swimmers ear (, is a common condition characterised by inflammation, infection, or irritation of the outer ear canal. It often occurs when water remains trapped in the ear after swimming or bathing, providing a moist environment conducive to bacterial or fungal growth.

- Acute otitis externa

- inflammation of <6 weeks

- rapid onset within 48 hours

- causes: bacterial infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus.

- associated with underlying skin conditions including contact dermatitis; acute otitis media; trauma to the ear canal; foreign body or obstruction in the ear canal; and water exposure.

- Chronic otitis externa

- inflammation >3 months

- causes: fungal infection with Aspergillus species or Candida albicans

- associated with diabetes mellitus or other causes of immunocompromise; or fungal infection due to prolonged topical antibiotic or corticosteroid use.

Signs and symptoms of acute and chronic otitis externa:

| Signs | Typical signs of Acute Otitis Externa | Typical signs of Chronic Otitis Externa |

|---|---|---|

| Tenderness of tragus/pinna | Present | N/A |

| Ear canal appearance | Red, oedamatous | Lack of ear wax, dry scaly skin |

| Tympanic membrane appearance | Erythema | N/A |

| Other signs | N/A | Conductive hearing loss, fluffy cotton-life black debris may be seen in the ear canal if fungal infection |

| Symptoms | Typical symptoms of Acute Otitis Externa | Typical symptoms of Chronic Otitis Externa |

|---|---|---|

| Ear itch | Present | Constant itch in the ear |

| Ear discharge | Present | N/A |

| Ear pain | Present | Mild discomfort or pain |

| Tenderness of tragus/pinna | Present | Present |

| Jaw pain | Possible | N/A |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of otitis externa is primarily clinical and based on patient history and physical examination (otoscopy and check lymph nodes).

Ask about any possible causes or risk factors, including recent ear trauma, use of hearing aids or ear plugs, history of head or neck radiotherapy.

Additional tests such as ear swabs for culture and sensitivity may be conducted to identify the causative organism and guide treatment if the condition is severe or recurrent.

Management of Acute Otitis Externa

- Keep the ear dry and clean (eg. avoid swimming for 7-10 days)

- Consider use of over-the-counter acetic acid 2% ear drops or spray (for people aged 12 years and older) morning, evening, and after swimming, showering, or bathing, for a maximum of 7 days.

- OTC analgesia – paracetamol/ibuprofen

- Consider prescribing a topical antibiotic preparation with or without a topical corticosteroid for 7–14 days (please refer to your local guidelines).

- Arrange follow-up if no improvement within 48-72 hours of starting initial treatment, symptoms not resolved after 2 weeks, cellulitis present beyond ear canal

Management of Chronic Otitis Externa

- Keep the ear dry and clean (eg. avoid swimming for 7-10 days)

- Consider use of over the counter (OTC) acetic acid 2% ear drops or spray (for people aged 12 years and older) morning, evening, and after swimming, showering or bathing for a maximum of 7 days

- OTC analgesia – paracetamol/ibuprofen

- Consider prescribing a topical ear preparation, depending on clinical judgement.

- If there are signs of fungal infection in the ear canal, options include:

- A topical antifungal preparation, such as clotrimazole 1% solution applied 2–3 times a day, to be continued for at least 14 days after infection has resolved.

- Clioquinol and a corticosteroid 2–3 drops twice daily for 7–10 days.

- Over-the-counter acetic acid 2% ear drops or spray (off label-indication, for people aged 12 years and older) morning, evening, and after swimming, showering, or bathing, for a maximum of 7 days.

- If there is suspected bacterial infection, manage as for acute otitis externa.

- If there is no obvious fungal or bacterial infection:

- Consider prescribing a topical corticosteroid preparation such as prednisolone ear drops 2–3 drops every 2–3 hours until symptoms improve, or betamethasone ear drops 2–3 drops 3–4 times a day. If symptoms improve, continue treatment using the lowest potency and/or frequency of application needed to control symptoms.

- If symptoms persist despite topical corticosteroid treatment, consider a trial of a topical antifungal preparation instead.

|

When to Refer for Acute Otitis Externa |

When to Refer for Chronic Otitis Externa |

|

Emergency Hospital Admission or Urgent Referral: |

Emergency Hospital Admission or Urgent Referral: |

|

Suspected malignant otitis externa or serious complications based on clinical judgement. |

Suspected malignant otitis externa or serious complications based on clinical judgement. |

|

Seek Specialist Advice or Referral to ENT Specialist (Urgency Depending on Clinical Judgement): |

Seek Specialist Advice or Referral to ENT Specialist (Urgency Depending on Clinical Judgement): |

|

Symptoms persist despite optimal management in primary care. |

Symptoms persist despite optimal management in primary care. |

|

Severe infection not responding to primary care management. |

Ongoing need for topical treatment beyond 2–3 months for symptom control. |

|

Elderly patients or those with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or other immunocompromising conditions. |

Elderly patients or those with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or other immunocompromising conditions. |

|

External ear canal occlusion obstructing topical treatment effectiveness. |

Ear canal occlusion hindering effective use of topical treatment. |

|

Need for specialist 'aural toilet' procedures like microsuction, ear wick insertion, or systemic antibiotics. |

Need for specialist procedures like microsuction or ear wick insertion. |

|

Cellulitis extending beyond the external ear canal that cannot be managed in primary care. |

Cellulitis extending beyond the external ear canal that cannot be managed in primary care. |

|

Consider Dermatology Referral: |

Consider Dermatology Referral: |

|

Suspected contact sensitivity to neomycin or another aminoglycoside ear preparation, ear plugs, hearing aids, or earrings. |

Suspected contact sensitivity to neomycin or another aminoglycoside ear preparation, ear plugs, hearing aids, or earrings. |

|

Patch testing may be necessary to confirm contact sensitivities. |

Patch testing may be necessary to confirm contact sensitivities. |

Paediatric Hearing - Otitis Media with Effusion (Glue Ear)

What is it?

Otitis Media with Effusion (OME), also known as, Glue Ear is a condition characterised by a collection of fluid within the middle ear space without signs of acute infection. OME may be associated with significant hearing loss, especially if it is bilateral and lasts for longer than 1 month.

Causes

- Over 50% of cases are thought to follow an episode of acute otitis media, especially in children under 3 years of age

- Persistence OME may occur because of one or more of the following:

- Impaired eustachian tube function causing poor aeration of the middle ear.

- Low-grade viral or bacterial infection.

- Persistent local inflammatory reaction.

- Adenoidal infection or hypertrophy.

Symptoms

- Muffled hearing (most common)

- Difficulty understanding speech, especially in noisy environments

- Earache (less common)

- Speech and language delays in children

Assessment

1. Detailed history

Examining a child's medical history helps diagnose OME.

Key points

Newborn hearing test: Checks for pre-existing hearing issues.

Hearing loss

- Difficulty understanding speech, especially in groups.

- Frequent requests to repeat things.

- High TV volume.

Ear discomfort

- Mild, occasional pain.

- Feeling of ear fullness or popping.

Tinnitus

- Ringing or buzzing in the ears.

Ear discharge

- Persistent, foul smell requires immediate medical attention.

Infections: Frequent ear infections, colds, or nasal congestion can increase risk.

Allergies: May contribute to Eustachian tube issues.

Sucking habits: Prolonged thumb sucking, pacifier use, or bottle feeding can be risky.

Snoring: May indicate breathing problems affecting the middle ear.

2. Examining with an otoscope is helpful, but a normal appearance doesn't rule out OME:

Signs of fluid build-up (effusion) are more likely if the eardrum shows:

- Abnormal colour: Yellow, amber, or blueish tinge.

- Disrupted light reflex: Light reflection appears weak or scattered.

- Cloudy appearance: Eardrum looks hazy beyond normal scarring.

- Air bubbles or fluid line: Visible air trapped within the fluid.

- Shape changes: Eardrum appears sunken (retracted), pushed inward (concave), or bulging outward.

Examine to assess for other factors that may predispose the child to OME including: Craniofacial anomalies, for example, Down syndrome and cleft palate, adenoid hypertrophy, asthma (including the presence of wheeze or dyspnoea), eczema or urticaria, conjunctivitis.

3. Assess the severity of the hearing loss and the impact on the child’s life and developmental status by asking about the following:

- Fluctuations in hearing.

- Lack of concentration or attention, or being socially withdrawn.

- Changes in behaviour.

- Listening skills and progress at school or nursery.

- Speech or language development.

- Balance problems and clumsiness.

Management

- For children with OME without hearing loss, provide reassurance that it will often get better over time and that no treatment is necessary. 50% of cases will resolve spontaneously within 6 weeks.

- If OME with hearing loss referral to audiology for formal assessment with tympanometry and hearing testing.

- The following pharmacological treatments are NOT recommended for treating OME, as there is no evidence to support their use:

Antibiotics, antihistamines, mucolytics, decongestants, corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, proton-pump inhibitors or anti-reflux medications.

Treatment can be grommet insertion.

If they have the surgical option of grommet insertion, the following is advice for treatment of infection/otorrhoea after grommet insertion: Grommets usually stay in place for 6-12 months then fall out.

- water precautions should be taken to keep the ear dry (such as avoiding swimming, and taking care when bathing or washing hair)

- use ear plugs or headbands if in contact with water

- consider ciprofloxacin for 5 to 7 days

Children should be followed up periodically by a GP when discharged from ENT or sooner if symptoms re-occur. If any concerns, their hearing should be re-assessed by an audiologist. If symptoms of OME recur, refer the child back to an ENT specialist.

Support for the child in the environment

- Being close to and facing the child when speaking to them.

- Minimising background noise.

- Using visual aids.

- Informing their teacher that the child has OME, and asking if adjustments can be made in school to help (for example, taking the steps above and having the child sit near the front of class).

- Preparing the child for interventions and ongoing management.

Further reading and references

OME under 12s Summary Decision Table to help parents understand the management options. It discusses the benefits, risks and practical considerations of each option: monitoring and support, auto-inflation, hearing aids, and grommets. Supportive strategies, for example modifying the environment and listening strategies.

GPnotebook - Otitis media (secretory)

Meniere’s Disease

Summary

Ménière's disease is a disorder of the inner ear that is characterised by episodes of vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and a feeling of fullness in the affected ear.

Signs and symptoms

Ménière's disease is characterised by spontaneous vertigo attacks, often described as spinning or rocking, accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

After the acute vertigo attack, the individual may experience unsteadiness for several days. Tinnitus, typically described as 'roaring,' initially occurs during attacks but can become permanent over time, significantly affecting quality of life.

Fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss, primarily in low frequencies and usually unilateral at first, eventually becomes permanent and does not fluctuate as the disease progresses.

Aural fullness, a sensation of pressure or discomfort in the ear, often precedes a vertigo attack and may occur during the episode, though it may not be present in advanced stages of the disease.

Usually, Ménière's disease manifests unilaterally, although bilateral cases have been reported, with symptoms not typically occurring simultaneously in both ears.

The attacks can involve predominantly aural symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, or ear fullness in the affected ear) and/or vertigo. These attacks typically last for a few hours, ranging from a minimum of 20 minutes to a maximum of 24 hours. They can occur in clusters over a few weeks, but periods of remission lasting months or years are also possible.

Assessment

- Head and neck examination findings are usually normal.

- Horizontal and/or rotatory nystagmus that can be suppressed by visual fixation may be present.

- The person may be unable to stand with their feet together and eyes closed (Romberg's test) or walk heel-to-toe (tandem) in a straight line.

- If asked to march on the spot with their eyes closed (Unterberger's test), the person may be unable to maintain their position and will turn to the affected side.

Red flags

- Rule out a cerebrovascular event in people with acute vertigo.

- Red flags for central pathology that require immediate hospital admission include:

- New unilateral hearing loss.

- Focal neurological signs (facial weakness, diplopia, or limb weakness).

When to refer to ENT

If Ménière's disease is suspected, refer to ENT services to confirm the diagnosis.

A definite diagnosis requires all of the following criteria:

- Two or more spontaneous episodes of vertigo, each lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours.

- Audiometrically documented low-to-medium frequency sensorineural hearing loss in one ear

- Fluctuating aural symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, or fullness) in the affected ear.

- Not better accounted for by an alternative vestibular diagnosis.

While awaiting referral, attacks of Ménière's disease–like symptoms may have to be managed in primary care.

Management

Reassure the person that although Ménière's disease is a long-term condition, vertigo usually significantly improves with treatment.