RCGP Safeguarding toolkit

| Site: | Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment |

| Course: | Clinical toolkits |

| Book: | RCGP Safeguarding toolkit |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 16 January 2026, 5:14 AM |

Description

The aim of this toolkit is to enhance the safeguarding knowledge and skills that GPs already have to enable them to continue to effectively safeguard children and young people, as well as adults at risk of harm.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Key questions in safeguarding

- Part 1: Professional safeguarding responsibilities

- Safeguarding responsibilities as a GP

- Safeguarding roles and responsibilities in general practice

- Safeguarding and personal wellbeing

- Managing concerns and allegations of abuse by colleagues, staff or anyone in a position of trust

- Safeguarding across the four UK nations

- Safeguarding in the independent or online/digital GP sector

- Part 2A: Identification of abuse and neglect

- The rights of children

- Adverse childhood experiences

- Safeguarding young people aged 16 and 17 years old

- Age of consent

- How does child abuse/neglect present in general practice?

- Obstacles to recognising and responding to child abuse and neglect

- Where do children experience abuse and neglect?

- Contextual safeguarding

- Children at greater risk of abuse and neglect

- Children who may be invisible to services

- Looked-after children

- Caring for refugee and unaccompanied asylum seeking children (UASC)

- Perinatal safeguarding

- Unseen men

- Disguised compliance

- Types of child abuse and neglect

- Physical abuse

- Perplexing presentations and fabricated or induced illness (FII)

- Neglect

- Was not brought (children)

- Emotional abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Talking about child sexual abuse

- Working with families affected by child sexual abuse

- Online child sexual abuse and exploitation

- Child sexual exploitation

- Child criminal exploitation and gangs

- Harmful sexual behaviour

- Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA)

- Child trafficking and modern slavery

- Female genital mutilation (FGM)

- Child abuse linked to faith or belief

- Bullying and cyberbullying

- Part 2B: Topics covering both child and adult issues

- Part 2C: Identifying adult abuse and neglect

- Types of adult abuse

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Psychological or emotional abuse

- Financial or material abuse

- Modern slavery

- Discriminatory abuse

- Neglect and acts of omission

- Self-neglect

- Organisational abuse

- Adults at greater risk of abuse and neglect

- How does adult abuse/neglect present in general practice?

- Safeguarding those who are homeless

- Was not brought (adult)

- Part 3A: Responding to abuse and neglect

- Part 3B: Responding to concerns about child abuse

- Part 3C: Responding to concerns about adult abuse

- Part 3D: Contributing to the lifelong holistic care of victims and survivors of abuse

- Part 3E: Responding to allegations of abuse regarding staff or persons in a position of trust (PiPoT)

- Part 4: Documenting safeguarding concerns and information

- Part 5: Information Sharing and multiagency working

- Guidance on information sharing

- What does ‘information sharing’ in a safeguarding context mean?

- The challenges of information sharing in general practice

- Why do we need to share information?

- When should we share information?

- What information should we share?

- Who should we share information with, and how?

- Information sharing and the law

- Consent

- Legal considerations for sharing personal information

- APPENDIX 1: Information sharing advice and guidance

- References

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

Welcome to the RCGP Safeguarding toolkit. This toolkit builds on the previous RCGP Child Safeguarding toolkit and RCGP Adult Safeguarding toolkit and combines both into one toolkit, aligned with the new RCGP Safeguarding Standards. The new standards are a whole-life course document covering both child and adult safeguarding, recognising that there are overlapping knowledge and capabilities in general practice.

Safeguarding in general practice has evolved significantly in recent years. General practice is a key partner in the multi-agency arena of safeguarding. Safeguarding can only be effective when professionals and agencies work together in partnership. Across the four UK nations, there are many similarities in safeguarding practice. There are, however, different legislations and local processes. This toolkit covers core knowledge that is applicable to all four nations and outlines some of the key differences in each nation. However, all practitioners need to be aware of the legislation, guidance and processes as it applies in their UK nation, which are highlighted later in this section.

Safeguarding in general practice can be defined as:

Contributing to the protection of children and adults from abuse and neglect using the specific skills, resources and capacity available in general practice by:

- implementing professional safeguarding responsibilities which includes continual professional development in safeguarding

- preventing abuse and neglect

- identifying abuse and neglect

- responding appropriately to abuse and neglect, including supporting victims and survivors of abuse

- having governance systems and processes in place to support safeguarding

- working collaboratively with other health colleagues, safeguarding partners and agencies.

The aim of this toolkit is to enhance the safeguarding knowledge and skills that GPs already have to enable them to continue to effectively safeguard children and young people, as well as adults at risk of harm.

Intended audience

This toolkit is for any GP or GP specialty trainee working in general practice in the UK and will also be useful for any practitioner working in general practice. Everyone is at a different stage in their GP career. For those who are new to general practice, or general practice in the UK, we recommend first completing the RCGP eLearning course on Core safeguarding in general practice (Level 3). These modules provide an overview of safeguarding in general practice in the UK and will also be useful to any practitioner as a safeguarding update or refresher. Completing the modules, along with the essential reading list below, will provide a solid background in safeguarding.

Essential reading list

This reading list is essential in understanding the principles of adult and child safeguarding, and should form part of your core knowledge around safeguarding:

- GMC. Protecting children and young people: The responsibilities of all doctors. 2018.

- GMC. Ethical hub - Adult safeguarding. Updated 2024.

- GMC. Good medical practice. 2024.

- Information Commissioner’s Office. A 10 step guide to sharing information to safeguard children. 2023.

- RCGP. GP online services toolkit. The GP online services toolkit contains a section on safeguarding challenges of online patient access. This is an essential read for anyone working in general practice where there is patient online access.

Key questions in safeguarding

These key questions link summary information from the toolkit to provide easily accessible information.

Presentations of child and adult abuse and neglect in general practice are seldom clear-cut and well-defined. Both children and adults can experience different types of abuse at the same time. There are many similarities to the presentations of different types of abuse, such as change in behaviour, mental health difficulties including self-harm, drug and alcohol use, disturbed sleep, and physical symptoms and signs.

Identifying abuse and neglect is not always easy. Knowing the signs of the different types of child and adult abuse helps to be able to identify possible concerns about abuse and neglect, as well as giving a voice to children and adults who are experiencing abuse.

Part 2 of the toolkit outlines the different types of abuse that children and adults can experience and how these might present in general practice. There are many signs that are common indicators of many different types of abuse such as behaviour changes and mental health concerns. Identification of any signs of abuse should prompt further exploration using professional curiosity.

Always keep abuse and neglect in mind as a potential cause for any reason a patient may present in general practice.

Responding to concerns about child abuse.

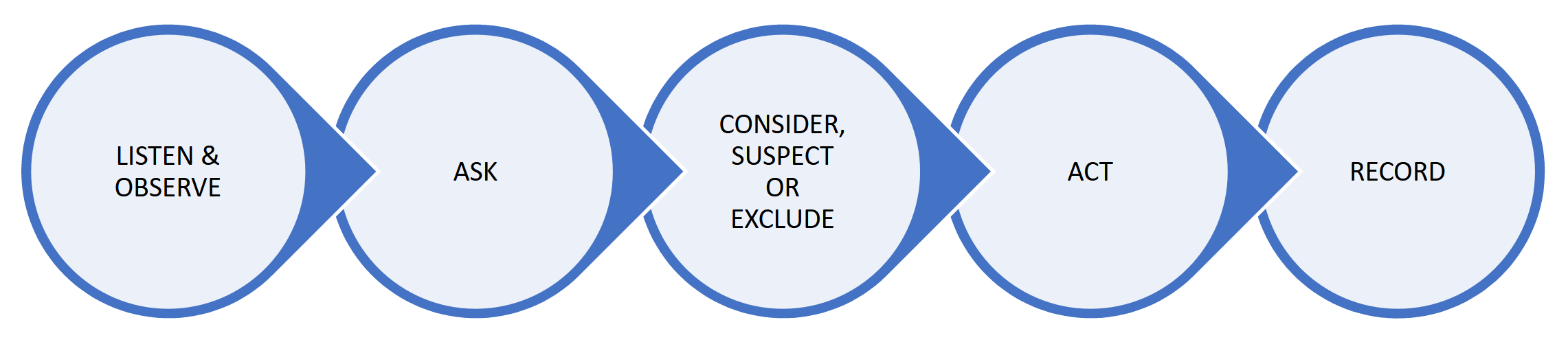

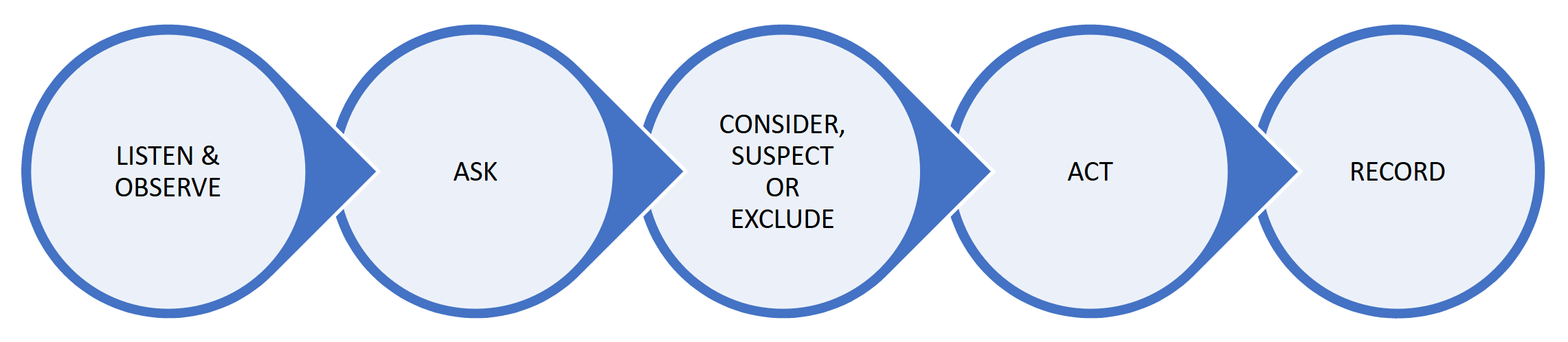

There are five steps to take. These are summarised here with further information and guidance in Part 3 of the toolkit.

- Step 1. Listen and observe. Piece together any information you already have about that child and family.

- Step 2. Ask. Seek an explanation for any injury, presentation or concern from both the parent or carer and the child/young person (if possible, dependent on age, communication needs, disabilities).

-

Step 3. Consider, suspect or exclude abuse or neglect:

- Consider – child abuse is one possible explanation for the concerns and is included in your differential diagnosis.

- Suspect – you have a serious level of concern about the possibility of child abuse (you do not need to have proof).

- Exclude – a suitable explanation is found for your concern.

-

Step 4. Act.

- If you suspect child abuse, you should follow your local multi-agency safeguarding processes and make a safeguarding referral to children’s social care/Health and Social Care Trust (Northern Ireland).

- If you are considering child abuse, you should decide on what further action needs to be taken, such as gathering further information, discussing your concerns and arranging review of the child.

- If you have excluded child abuse at this time, you should continue to exercise professional curiosity and be prepared to once again consider or suspect child abuse should the situation change, or new information come to light.

- Step 5. Record. Ensure clear documentation in the child’s record (and that of any other family member as appropriate). Mark entries ‘not for online access’.

Responding to concerns about adult abuse.

There are five steps to take. These are summarised here with further information and guidance in Part 3 of the toolkit.

- If you are unsure, seek further advice from a colleague, your organisational safeguarding lead or local safeguarding professionals.

- Ensure the patient is safe and deal with any immediate medical needs.

Is the adult an 'adult at risk/adult at risk of harm'?

YES: consider an adult safeguarding referral and follow steps 4 & 5 below.

NO: consider:- other sources of support for the adult

- whether any others are at risk of harm and for whom a safeguarding referral needs to be considered, such as any children or other adults who are adults at risk of harm

- whether the level of harm is potentially so serious that a different type of referral is required such as a MARAC referral in the cases of high-risk domestic abuse

- reassess the situation if new relevant information comes to light

- Continue to monitor the situation as risk and the ability to safeguard themselves may change over time.

Does the adult at risk of harm have capacity to make a decision about a safeguarding referral?

NO: proceed with an adult safeguarding referral.

YES and they consent to a referral: proceed with an adult safeguarding referral.

YES but they do not consent to a referral: consider:- whether they need more information on the safeguarding adult process, which might address any concerns they have

- what other sources of support are available

- whether any others are at risk of harm and for whom a safeguarding referral needs to be considered, such as any children or other adults who are adults at risk of harm

- whether the level of harm is potentially so serious that a different type of referral is required such as a MARAC referral in the cases of high-risk domestic abuse

- reassess the situation at appropriate intervals as risk can change as can an adult’s ability to protect themselves.

- reassess the situation if new relevant information comes to light

UNCERTAIN: discuss with a colleague, your organisational safeguarding lead or local safeguarding professionals.

NOTE FOR PRACTITIONERS WORKING IN WALES – all practitioners working in Wales should be aware of the statutory ‘duty to report’.

- The practice/organisation safeguarding lead.

- A more experienced colleague.

- The Caldicott Guardian or Data Protection Officer if you need advice about information sharing.

- Local safeguarding professionals such as Named GPs/Nurses for Safeguarding, Designated Health Professionals, safeguarding leads within health boards.

- Social worker – you can contact your local authority/Health and Social Care Trust by phone and ask to speak to the duty social worker if you have an urgent safeguarding concern. You can find these numbers on the safeguarding section on the website of your local authority, or in Northern Ireland, your local Health and Social Care Trust.

- The phone numbers for your local safeguarding professionals, local authority, Health and Social Care Trust (Northern Ireland), should be clearly displayed and easily accessible within your organisation.

- For practitioners in England, the NHS Safeguarding App is an easy way to find your local authority details. It can be accessed by visiting your device’s appropriate app store and searching for ‘NHS Safeguarding’.

Information sharing is essential to safeguarding children and adults.

Sharing information in a safeguarding context means sharing relevant personal information about children and adults that multi-disciplinary and multi-agency professionals and agencies hold. The information is shared in order to safeguard children and adults from abuse and neglect.

Below are the key principles of information sharing and a summary of the ‘Why, When, Who, What and How’ of information sharing. Further guidance, including on issues around consent, can be found in Part 5 of the toolkit.

You can also find more guidance on making child and adult safeguarding referrals in Part 3 of the toolkit (if needed).

Summary of the ‘Why, When, Who, What and How’ of information sharing for the purposes of safeguarding:

When there is a concern that a child is at risk of, or is experiencing, abuse or neglect.

When there is a concern that an adult is at risk of, or is experiencing, abuse or neglect and one of the following:- It is required by law.

- The adult provides consent for the information to be shared.

- The adult does not have the capacity to provide consent for the information to be shared.

- It is in the public interest, i.e. there are others at risk of serious harm, or it is necessary to share information to prevent a serious crime or there is an imminent risk of serious harm to the individual.

Information can also be shared when safeguarding advice is being sought – this can often be done without sharing the names or other identifying features of the patient involved.

- General practice multi-disciplinary team.

- Wider health multi-disciplinary team.

- Multi-agency safeguarding partners.

- Other relevant agencies as appropriate.

- High quality documentation of safeguarding information is fundamental to safeguarding children and adults in order to:

- ensure victims and survivors of abuse have the healthcare and support they need

- allow a picture to be built over time of emerging concerns

- manage and share information about risk appropriately

- allow for effective information sharing when required

- allow for discussions with patients about online access where there are safeguarding concerns.

- Experiencing abuse and/or neglect as a child or adult has significant implications on health and wellbeing so therefore needs to be documented.

- All safeguarding information should be stored within the medical record, not separate to it.

- Any documents containing third party information should be flagged as such with the appropriate code.

- It is not necessary to black out information within safeguarding documents before putting into the patient record.

- The use of coding to record key safeguarding information is important to be able to easily find the relevant information when needed in the future or for audit purposes.

- Safeguarding information should be managed safely to reduce the risk of perpetrators using any disclosures of abuse from victims (or any information in the medical record) to further abuse them.

- If any member of staff is unsure how to manage safeguarding information, they should always seek advice from the practice safeguarding lead/Caldicott Guardian/Information Governance lead/Data Protection Officer.

- All safeguarding information should be redacted from patient online access and clearly marked ‘not for online access’.

Further information and guidance on documenting and coding safeguarding information.

Having knowledge of local safeguarding policies and procedures is essential to effective safeguarding. This table outlines the knowledge you need so that you can take prompt safeguarding action when necessary. Please access the downloadable version of the table (DOCX).

How do I contact them?

How do I contact them?

Safeguarding learning is a continual process and enables us to have the knowledge and capabilities to safeguard our patients.

The RCGP Safeguarding Standards set out the professional safeguarding standards and safeguarding training requirements for GPs and anyone working in any general practice setting in the UK. This includes, but is not limited to, NHS GP practices, independent and online providers of general practice services, Primary Care Networks (PCNs), GP out of hours and extended access services. The standards combine and include both safeguarding children and adults and are a whole life course document. These standards form part of the wider intercollegiate documents on safeguarding knowledge and competencies for all healthcare staff.

It is important to note that both adult and child safeguarding knowledge and capabilities are equally necessary and expected for all staff in general practice, even if the staff member only works with adults.

The RCGP Safeguarding Standards set out five key areas of safeguarding knowledge and capabilities, shown here.

- Understanding statutory, legal, professional and employment safeguarding responsibilities and duties, including the obligation to act when there is a safeguarding concern.

- Preventing abuse and neglect as far as possible through timely action and intervention.

- Accounting for the influence of personal beliefs, experience and attitudes.

- Maintaining individual wellbeing.

- Supporting colleague wellbeing.

- Recognising indicators and signs of all types of abuse and neglect in children and adults.

- Identifying children and adults who may be more vulnerable to abuse and neglect.

- Applying principles of consent, confidentiality and capacity in relation to safeguarding.

- Mitigating barriers to healthcare faced by victims and survivors of abuse.

- Understanding the lifelong impact of abuse.

- Learning from those with lived experience of abuse.

- Practising in a trauma-informed way.

- Applying relevant legislation.

- Being vigilant and addressing organisational/institutional abuse/neglect.

- Acting when there is a safeguarding concern.

- Talking to children, adults, families, parents and carers about abuse.

- Following local referral processes for child and adult safeguarding.

- Contributing to the lifelong holistic care needed by victims and survivors of abuse.

- Seeking advice and guidance and escalating concerns when necessary.

- Promptly acting on, and responding appropriately to, any concerns or allegations about persons in a position of trust.

- Documenting safeguarding concerns accurately and safely in the patient record.

- Managing safeguarding documents in line with best practice in information governance and data protection.

- Proactively addressing safeguarding challenges of patient online access including coercion to access records.

- Participating in multi-agency and multi-disciplinary working.

- Sharing information appropriately and proactively in a safeguarding context.

- Contributing to safeguarding reviews.

- Learning from safeguarding serious case reviews (local and national).

This table gives a summary of the safeguarding training requirements as set out in the RCGP Safeguarding Standards for GPs and anyone working in a general practice setting in the UK. Also see ‘RCGP safeguarding standards for general practice’.

- Receptionists, administrative and secretarial staff (with the exception of manager/lead roles of these groups who will need level 2).

- Volunteer staff.

- Safeguarding included in practice/organisation induction AND completion of relevant safeguarding level 1 eLearning updates.

- Level 1 safeguarding update.

- Practice managers (including deputy managers) and equivalent leadership roles. [ALSO SEE ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THIS GROUP]

- Care navigators.

- Reception managers.

- Safeguarding administrators.

- Managers/leads of administrative/secretarial teams.

- Health care assistants, pharmacy technicians.

- Safeguarding included in practice/organisation induction AND completion of relevant safeguarding level 2 eLearning updates.

- Complete relevant safeguarding level 2 eLearning modules.

- Have a safeguarding induction with an appropriate senior leader e.g. practice manager/practice safeguarding lead depending on nature of role. This induction should include:

- discussion about the safeguarding structure, policies and procedures within the practice/organisation

- identification of any areas of professional development related to safeguarding.

- Level 2 safeguarding update

- GPs, practice nurses, physician associates, nursing associates, pharmacists, paramedics, Advanced Care Practitioners, Advanced Nurse Practitioners, social prescribers, mental health workers, physiotherapists, podiatrists, dieticians and any similar ARRS (Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme) roles.

- Primary care network (PCN) safeguarding roles in England such as PCN safeguarding co-ordinators.

- GP speciality trainees [who should refer to the specific safeguarding training requirements for the workplace based assessment (WBPA) part of the MRCGP exams]

- Safeguarding included in practice/organisation induction.

- Completion of relevant safeguarding level 3 eLearning updates (or provide evidence of prior completion) e.g. RCGP modules.

- Meet with the practice/organisational safeguarding lead, their deputy, or other relevant senior leader within one month of starting their new role to:

- discuss the safeguarding structure, policies and procedures within the practice/organisation

- identify any areas of professional development need related to safeguarding.

- Level 3 safeguarding update.

- Completion of the Safeguarding Structured Reflective Template to demonstrate reflection and learning across the breadth of all the five areas of safeguarding knowledge and capabilities. This must include both child and adult safeguarding issues, even if a practitioner only works with adults.

Annually:

- Safeguarding update.

- Demonstrate regular attendance at the local practice safeguarding lead forums (if available in the locality).

- Demonstrate an example of reflection/learning aligned with the practice/organisational role specific knowledge and capabilities.

- The practice/organisation safeguarding lead.

- A more experienced colleague.

- Caldicott Guardian or Data Protection Officer, if you need advice about information sharing.

- Local safeguarding professionals such as Named GPs/Nurses for Safeguarding, Designated Health Professionals, or safeguarding leads within health boards.

- Social worker – you can contact your local authority (Health and Social Care Trust in Northern Ireland) by phone and ask to speak to the duty social worker if you have an urgent safeguarding concern.

For those who are new to general practice, or general practice in the UK, we recommend first completing the RCGP eLearning course - Core Safeguarding in General Practice (Level 3). These modules provide an overview of safeguarding in general practice in the UK and will also be useful to any practitioner as a safeguarding update or refresher. Completing the modules, along with the essential reading list, will provide a solid background in safeguarding.

When you have completed the eLearning modules and the essential reading list, you will have a great foundation in safeguarding that you can build throughout your career in UK general practice. See ‘What safeguarding training do I need?’ above for further information on training requirements.

- A resource for busy GPs and general practice staff to refer to when they need safeguarding support or are unsure of what steps to take when they have a safeguarding concern about an adult or child.

- An educational resource to support the building and development of safeguarding knowledge and capabilities. Some practitioners might dip in and out of the toolkit when they need to, others may read through it systematically over time to support their safeguarding learning.

- A resource for practice safeguarding leads to use to support safeguarding learning and reflection in their organisation.

There are five parts to the toolkit – these match the five different key areas of safeguarding knowledge and capabilities set out in the RCGP Safeguarding Standards. Contents of the toolkit are summarised below:

- Essential reading list.

- Safeguarding roles and responsibilities in general practice.

- Safeguarding and personal wellbeing.

- Summary of relevant safeguarding legislation and guidance in each UK nation.

- Identifying child abuse and neglect:

- the rights of children

- adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

- safeguarding young people aged 16 and 17 years old

- age of consent, Fraser guidelines and Gillick competence

- how does child abuse/neglect present in general practice?

- obstacles to recognising and responding to child abuse and neglect

- where do children experience abuse and neglect

- contextual safeguarding

- children at greater risk of abuse and neglect

- children who may be invisible to services

- looked after children

- caring for refugee and asylum seeking children

- perinatal safeguarding

- unseen men

- disguised compliance

- types of abuse and neglect (including Was Not Brought).

- Radicalisation (covers child and adults).

- Domestic abuse (covers child and adults) including ‘honour’ based abuse and forced marriage.

- Transitional safeguarding.

- Identifying adult abuse and neglect:

- human rights based approach

- principles of safeguarding

- types of abuse and neglect

- organisational abuse including safeguarding in care homes

- adults at greater risk of abuse and neglect

- how does adult abuse/neglect present in general practice

- safeguarding those who are homeless

- Was not brought.

- How should we respond when we have concerns that a child or adult is experiencing abuse or neglect?

- Responding appropriately and effectively in general practice to concerns about abuse.

- Talking to children, adults, families and carers about abuse.

- Trauma-informed practice.

- Responding to concerns about child abuse:

- the child’s voice

- five-step process to responding to concerns about child abuse and neglect:

- listen and observe

- ask

- consider, suspect or exclude

- act

- document

- early Help

- making a child safeguarding referral

- top tips for making a child safeguarding referral and writing safeguarding reports– The 5 Cs

- working with parents and carers when there are safeguarding concerns about their children/the children they care for

- child protection system in the UK.

- Responding to concerns about adult abuse:

- five-step process to responding to concerns about adult abuse and neglect:

- concern about abuse

- the views of the adult

- is the adult an ‘adult at risk of harm’?

- assessing mental capacity (includes mental capacity principles, decisional and executive capacity, ‘unwilling’ or ‘unable’ to safeguard, assessing capacity in complex situations and in self-neglect, giving medication covertly

- is a safeguarding referral needed?

- what should happen if an adult at risk of harm has capacity but does not want any safeguarding procedures and is unwilling to take steps to safeguard themselves

- making safeguarding personal

- making an adult safeguarding referral

- top tips for making an adult safeguarding referral and writing safeguarding reports – the 5 Cs

- adult safeguarding processes.

- five-step process to responding to concerns about adult abuse and neglect:

- Contributing to the lifelong holistic care of victims and survivors of abuse.

- Responding to allegations of abuse regarding staff or persons in a position of trust (PiPoT).

- Documenting and coding safeguarding information in the electronic medical record.

- Key principles of documenting safeguarding concerns and information in the patient electronic medical record.

- Who is responsible for managing safeguarding information in the practice/organisation?

- What is ‘safeguarding information’?

- Sources of safeguarding information.

- Recording family groups/relationships.

- Domestic abuse – specific guiding of domestic abuse and MARAC information.

- Recording adult drug and alcohol problems, mental health problems and learning disabilities.

- ‘Was not brought’.

- Management of child protection conference invitations, reports (including those provided by general practice and those received) and minutes.

- Management of adult safeguarding conference invitations, reports(including those provided by general practice and those received) and minutes.

- Contextual safeguarding situations.

- Information about perpetrators of abuse.

- Codes to use.

- Managing safeguarding information in the context of patient online access.

- Key principles of information sharing.

- The challenges of information sharing.

- The why, when, who, what and how of information sharing.

- Information sharing and the law.

- Consent.

These two templates have been developed to support safeguarding learning and reflection. They can be used to support annual appraisal as well as revalidation.

Part 1: Professional safeguarding responsibilities

This section covers the safeguarding responsibilities for all those working in general practice in the UK as well as outlining specific safeguarding roles in general practice.

Safeguarding responsibilities as a GP

Safeguarding duties and responsibilities for all doctors working in the UK, including GPs, are set out by the General Medical Council (GMC).

The GMC highlights the importance of safeguarding in their guidance for doctors; all GPs should be familiar with, and follow, these professional standards. The GMC standards with particular relevance to safeguarding are:

- Good medical practice. 2024.

- Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information. Updated 2018.

- Protecting children and young people: the responsibilities of all doctors. Updated 2018.

- 0 – 18 years: guidance for all doctors. Updated 2018.

- Adult safeguarding ethical hub (this ethical hub shows how the GMC professional standards can be applied in adult safeguarding).

Good medical practice 2024 includes the following guidance on safeguarding:

“Safeguarding children and adults who are at risk of harm

- You must consider the needs and welfare of people (adults, children and young people) who may be vulnerable, and offer them help if you think their rights are being abused or denied. You must follow our more detailed guidance on Protecting children and young people and 0-18 years: guidance for all doctors.

- You must act promptly on any concerns you have about a patient – or someone close to them – who may be at risk of abuse or neglect, or is being abused or neglected.”

Safeguarding roles and responsibilities in general practice

Everyone in the practice team has a responsibility for safeguarding and each member plays a crucial role. The RCGP Safeguarding Standards outline the safeguarding knowledge and capabilities for GPs and anyone working in any general practice setting in the UK.

All regulated clinical staff have safeguarding roles and responsibilities set out in guidance from relevant professional regulators (for example, General Medical Council, Nursing and Midwifery Council, General Pharmaceutical Council, Health & Care Professions Council). All staff should have their safeguarding duties and responsibilities outlined in their terms of employment.

Practice Safeguarding Lead

All practices should have a Practice Safeguarding Lead. The specifics of this role are outlined in the RCGP Safeguarding Standards document. There may also be a Deputy Safeguarding Lead (practices in England should be aware that ‘Working Together to Safeguard Children 2023: statutory guidance’ states that: "GP practices should have a lead and deputy lead for safeguarding, who should work closely with the named GP ”*). The role of the safeguarding lead is to support safeguarding within the practice, not to manage all safeguarding activity.

*Named GPs only exist in England and are GPs employed by an ICB (Integrated Care Board) to advise and support GP practice safeguarding leads (Working Together to Safeguard Children 2023: statutory guidance).

Practice managers

Practice managers play a crucial role in safeguarding in general practice by demonstrating safeguarding leadership, embedding safeguarding culture, and in particular, ensuring safe recruitment processes. The safeguarding specifics of this role are outlined in the RCGP Safeguarding Standards document.

Safeguarding Administrators

Practices should consider having a Safeguarding Administrator (practices use different terms) – this is a member of the Practice administrative team who, depending on size of practice and structure, either manages or oversees, the recording and coding of safeguarding information coming in and out of the practice. The role of safeguarding administrator does not need to be the individual’s sole role, but someone in the administrative team with the appropriate safeguarding knowledge, capabilities and responsibility. The safeguarding administrator should receive ongoing training and support for their role as set out in the RCGP Safeguarding Standards.

Safeguarding support roles

As practices evolve, and with the establishment of Primary Care Networks (PCNs) in England, there has been development of safeguarding support roles, such as safeguarding co-ordinators, within practices/PCNs. This role can be extremely varied depending on the background and experience of the individual which can range from an administrative role within a current practice structure to a safeguarding nurse employed by a number of PCNs.

The principle of the role is to support safeguarding work in primary care.

Practices/PCNs should be aware that safeguarding support roles in primary care:

- Are new, therefore caution, time and patience are needed with their development and integration.

- Are only one part of safeguarding practice and culture in primary care – safeguarding remains the responsibility of ALL staff members.

- Are an addition to current safeguarding practice and culture in primary care, not a replacement.

- Have no national standard as the role varies between practices and PCNs.

- Are recruited from a wide variety of individuals therefore experience and ability varies hugely.

- Will need significant supervision and guidance from the practice safeguarding lead and other relevant senior practice team members in line with their role, learning needs and expectations of the practice.

- Should not make any clinical or safeguarding decisions.

- Should have a clear job role with clear governance and escalation processes embedded.

- Should have the appropriate indemnity for their role.

The role can include:

- Managing the safeguarding diary of child protection and adult safeguarding conferences to support timely report completion and also to maximise GP attendance at these conferences where possible.

- Assisting GPs with preparation of safeguarding reports for safeguarding meetings and conferences e.g completing demographics and factual information such as missing vaccinations, ‘was not brought’ information, outstanding health referrals.

- There should be robust supervision and governance structures in place within the practice regarding the preparation of reports to ensure appropriate, relevant and proportionate information is shared

- Administrative staff should not interpret clinical information within a record for the purpose of a safeguarding report

- The responsibility of the completion of safeguarding reports remains with GPs

- Supporting with safeguarding coding from safeguarding documents coming into the practice.

- Liaison with patients/families regarding any outstanding health issues raised through safeguarding conferences, e.g. liaising with parents to book appointments for a child’s health needs (such as vaccinations or health reviews) when a child is on a child protection plan.

- Maintain up to date registers/coding of children on child protection plans and looked after children.

- Help to support clinicians following up children and adults who are not brought to appointments. For example, by contacting them and arranging another appointment.

- Co-ordinate practice safeguarding meetings.

- Collate and maintain staff safeguarding training registers.

- Work closely with the practice safeguarding lead and practice manager.

At this current time, given the infancy of safeguarding support roles, it is generally not appropriate for individuals in these roles to attend child or adult safeguarding conferences/strategy meetings for the following reasons:

- Children and adults at risk of harm who are subject to child protection /adult safeguarding conferences are some of our most vulnerable patients. These conferences can be extremely difficult for families/adults and it is essential they are treated with respect.

- There are no ‘‘observational’ roles at a safeguarding conference. Every professional there must actively participate in the discussions and decision making.

- Professionals present need to be able to analyse, understand and interpret the information presented by all agencies as well as by the child/family/adult/carers.

- Professionals present need to be able to understand a wide range of risks involved in the situation and partake in any risk assessments.

- The professional representing primary care needs to be able to explain and interpret health information to non-health professionals, including the patient/family/carers.

- Professionals need to be able to respectfully challenge other agencies/professionals if appropriate and need to have sufficient authority to do so. They also need to be able to respond to respectful challenge towards themselves, their colleagues or their organisation.

Safeguarding and personal wellbeing

Safeguarding is part of the holistic care given to patients in general practice and it can be very rewarding to be involved in preventing and stopping abuse happening. However, there is no doubt that being involved in safeguarding can be professionally and personally challenging. Safeguarding requires us as professionals to ‘think the unthinkable’ which can make us feel very uncomfortable, especially as GPs, when trust, empathy and compassion are key to our therapeutic relationships with patients. Being involved in safeguarding cases or hearing personal experiences of abuse from patients can be very upsetting. There is also emotional complexity involved as in general practice we provide care for both victims and perpetrators of abuse. This complexity can be magnified by the contextual experiences of perpetrators of abuse who have their own experiences of being a victim of abuse. A key element of a GP’s role has always been to be an advocate for patients. This role can be conflicted when a patient is causing harm to others and this can be challenging to deal with.

In addition, for any healthcare professional who is a victim or survivor of abuse themselves, professionally having to deal with concerns about abuse to children or adults can be very difficult and can trigger unwanted memories and emotions.

Talking to colleagues can be very helpful – whether this is to simply debrief after a difficult consultation or experience, or to seek advice and guidance. Support, advice and guidance can also be sought from the practice safeguarding lead and/or local safeguarding professionals such as named GPs/nurses, Designated Health Professionals or safeguarding leads within health boards.

The most important thing to remember is that no practitioner has to deal with difficult safeguarding issues alone – there is always help available.

There are lots of resources available for your own wellbeing. The links below are for national organisations, you may also have sources of local support such as through your practice/organisation, your GP, local agencies who support victims and survivors of abuse or via your LMC (Local Medical Committees).

- GMC. Wellbeing resources for doctors. 2022.

- BMA. Your wellbeing. 2024.

- NHS. Practitioner Health. 2024. Practitioner Health is a free, confidential NHS primary care mental health and addiction service with expertise in treating health and care professionals.

- NAPAC. Supporting Recovery From Childhood Abuse. 2023. The National Association of People Abused in Childhood: supports adult survivors of any form of child abuse.

- The Survivors Trust. Homepage of The Survivors Trust. Supporting victims and survivors of sexual violence.

- Refuge. Homepage of National Domestic Abuse Helpline. Supporting victims and survivors of domestic abuse.

Managing concerns and allegations of abuse by colleagues, staff or anyone in a position of trust

This is covered in Part 3 of the toolkit: Responding to abuse and neglect.

Safeguarding across the four UK nations

Safeguarding responsibilities apply to everyone working in healthcare in all of the four UK nations. Each nation has their own safeguarding legislation and guidance which all staff in general practice should be aware of in the nation in which they work. Key legislation and guidance for each UK nation are shown below.

England

Legislation

- Children Act 1989.

- Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003.

- Children Act 2004.

- Mental Capacity Act 2005.

- The Care Act 2014.

- Children and Social Work Act 2017.

- Domestic Abuse Act 2021.

Further details about child protection legislation and guidance in England regarding children can be found on the NSPCC website.

Guidance

- Department for Education. Working together to safeguard children. Updated 2024.

- HM Government. What to do if you’re worried a child is being abused. Advice for practitioners. 2015.

- Home Office. Mandatory Reporting of Female Genital Mutilation – procedural information. 2016.

- HM Government. Multi-agency statutory guidance on female genital mutilation. 2020.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Care and support statutory guidance. Updated 2024.

- Department for Constitutional Affairs. Mental Capacity Act 2005. Code of Practice. 2007.

- Department for Education. Information Sharing. Advice for practitioners providing safeguarding services for children, young people, parents and carers. 2024.

Northern Ireland

Legislation

- The Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995.

- Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003.

- The Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups (Northern Ireland) Order 2007.

- Safeguarding Board Act (Northern Ireland) 2011.

- Children’s Services Co-operation Act (Northern Ireland) 2015.

- Mental Capacity Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 and Mental Capasity Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 by Department of Health.

Further details about child protection legislation and guidance in Northern Ireland regarding children can be found on the NSPCC website.

Guidance

- Safeguarding Board for Northern Ireland. Procedures Manual. Updated 2023.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety and and the Department of Justice. Adult Safeguarding: Prevention and Protection in Partnership. 2015.

- Multi-agency practice guidelines: Female Genital Mutilation.

Scotland

Legislation

- Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000.

- Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act

- The Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007).

- Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014.

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Act 2024.

Further details about child protection legislation and guidance in Scotland regarding children can be found on the NSPCC website.

Guidance

- Scottish Government. Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007: guidance for General Practice. 2022.

- Scottish Government. Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007: Code of Practice. 2022.

- Scottish Government. Adults with incapacity: guide to assessing capacity. 2008.

- Scottish Government. NHS Public Protection Accountability and Assurance Framework. 2022.

- Scottish Gorvernment. Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) - Statutory Guidance - Assessment of Wellbeing 2022 – Part 18 (section 96) of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. 2022.

- Scottish Government. National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland 2021. Updated 2023.

- Scottish Government. Responding to female genital mutilation: multi-agency guidance. 2017.

- National Trauma Transformation Programme. Homepage of NTTP. Responding to Psychological Trauma in Scotland.

- National Adult Support and Protection Coordinator. Adult Support and Protection: Scotland. Seven minute briefing. 2024.

Centre for Excellence for Children’s Care and Protection. Child Protection: Scotland. Seven minute briefing. 2025.

Wales

Legislation

- Children Act 1989.

- Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003.

- Children Act 2004.

- Mental Capacity Act 2005.

- Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014.

- Violence against Women, Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence (Wales) Act 2015.

Further details about child protection legislation and guidance in Wales regarding children can be found on the NSPCC website.

Guidance

- Social Care Wales. Wales Safeguarding Procedures. 2024.

- Welsh Government. Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014. Working Together to Safeguard People: Code of Safeguarding Practice. 2022.

- Welsh Government. Safeguarding Guidance. Updated 2024.

- Home Office. Mandatory Reporting of Female Genital Mutilation – procedural information. 2016.

- HM Government. Multi-agency statutory guidance on female genital mutilation. 2020.

- Department for Constitutional Affairs. Mental Capacity Act 2005. Code of Practice. 2007.

Safeguarding in the independent or online/digital GP sector

Patients can choose to be seen via the NHS or via the independent sector, or in combination with the independent health appointments forming a 'complimentary service'. Some patients will elect for all of their care to be in the independent sector. There are also online/digital providers of GP services.

Legal and professional responsibilities around safeguarding are the same regardless of whether the healthcare setting is an NHS or non-NHS/independent/online/digital setting. For doctors, the GMC professional standards apply regardless of the healthcare setting.

GPs working in the independent or online sectors can face additional challenges in safeguarding patients due to:

- Limited access to patients' NHS GP and hospital health records.

- Patients may decline to share information regarding private consultations with their NHS GP which can lead to concerns and problems.

- Unverified information being provided such as demographic information which may not be genuine because it is not always cross checked. This means that patients can 'disappear' or be hard to trace.

- Less reliable computer systems to code non-attendance or 'was not brought' and other issues that might raise safeguarding suspicions. Multiple non-attendances are less likely to be flagged as a potential safeguarding issue.

- Multi-agency safeguarding information is not routinely shared with the independent sector.

- There may not be clear processes for reporting safeguarding concerns. This can be a particular issue for online providers who may see patients from across the UK.

- Families not being registered with the same independent sector practice or an NHS GP practice and therefore not visible.

- Parents or carers choosing not to share relevant information and no robust system to cross check with the more extensive NHS note keeping systems, such as hospital records or nursing and midwifery records that are often easily accessible within an NHS GP setting.

- Lack of robust standardised systems to ensure referral outcomes are communicated back to the referring independent GP from consultants and specialists.

- No robust system being in place for sharing information with their patient's usual NHS GP. This may be a problem if patients are seen when on holiday or out of their usual catchment area for other reasons.

- Potentially underused standardised pathways and protocols for safeguarding referrals in the independent setting compared to regularly used protocols and pathways in the NHS.

- Recognising abuse in affluent families can be difficult, for example child neglect can be much less visible. There can also be challenges working with parents from affluent and professional backgrounds.

- Independent clinics may only see adults and therefore children and any dependent adults may be less visible.

- Parents' perceptions that they are paying for a ring fenced specific medical service which does not invoke any safeguarding intervention by the independent GP.

- Potential differences in private patients' medical cultural background and their understanding of UK standards and the doctor's statutory duties under UK safeguarding regulations.

- Private patient expectations of 'control' over the private consultation and GP.

What can GPs working in the independent and online/digital sector do to ensure safeguarding is embedded into their practice?

Always consider safeguarding

- Always consider child and adult safeguarding in every interaction with a patient.

- Even if an

independent setting only has adult patients, practitioners in these

settings must always be mindful of children. The GMC in their

guidance Protecting children and young people: The responsibilities of all doctors, states:

“You must consider the safety and welfare of children and young people, whether or not you routinely see them as patients. When you care for an adult patient, that patient must be your first concern, but you must also consider whether your patient poses a risk to children or young people. You must be aware of the risk factors that have been linked to abuse and neglect and look out for signs that the child or young person may be at risk.” - Ensure knowledge and awareness of specific types of abuse where perpetrators may seek to use the independent health sector to obtain medical treatment for victims of abuse but evade wider multi-agency involvement. For example, modern slavery, trafficking, sexual and criminal exploitation, domestic abuse, ‘Honour-based’ abuse, Fabricated and Induced Illness.

- Be aware that some patients may seek to use independent healthcare to evade statutory services, especially when there are safeguarding concerns.

- Understand how abuse might present in affluent families.

- Understand, and be able to respond to, the challenges of safeguarding in affluent communities.

- Consider how safeguarding concerns will be further explored or followed up in a setting where patients pay for consultations. Where a cost may normally be attributed to patient contacts, this should never be a barrier for carrying out appropriate safeguarding activity. For example, in situations where you are ‘considering’ abuse or neglect as a possible cause for a patient’s presenting symptoms or situation, how will you explore and follow this up if the patient does not wish to pay for further consultations?

- Work closely with colleagues and discuss any safeguarding concerns early.

Safeguarding training

- Attend regular safeguarding training and ensure training is up to date and relevant to role – GPs and all general practice staff, regardless of whether they work in the NHS, independent or online sector, require the same level of safeguarding training as set out in the RCGP Safeguarding Standards. These standards include child and adult safeguarding equally and are applicable even if the independent GP service sees only adult patients.

- Consider how the organisation keeps itself up to date with safeguarding national guidance and case reviews.

Safeguarding policies and procedures

- Ensure safeguarding responsibilities and policies are clear and visible on the organisation’s website and available to staff in consulting rooms.

- Ensure there are policies in place regarding information sharing and that these are clear and visible on the organisation’s website.

- Ensure all staff members are aware of and have read the organisation’s safeguarding policies.

- Ensure local safeguarding referral processes and contact numbers are kept up to date and easily accessible to all staff members. In England, the NHS Safeguarding App (4) is a comprehensive resource and includes links to all safeguarding partnerships within England.

- Providers of online and remote GP services should be aware of the specific challenges this brings with regards to safeguarding such as providing care across a large geographical area including delivering care across national and international borders – providers should ensure they have processes in place to identify safeguarding concerns and respond appropriately.

- The following documents will be helpful for online providers to ensure

they are providing a safe service:

- CQC. The state of care in independent online primary health services. Findings from CQC’s programme of comprehensive inspections in England. Updated 2022.

- FSRH/BASHH. Standards for Online and Remote Providers of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. 2019.

- If the organisation provides virtual consultations, be clear on how safeguarding concerns can be identified and followed up.

- If the organisation provides questionnaire-based interactions with clinicians, consider how safeguarding concerns can be identified and followed up.

- Encourage patients to also register with an NHS GP.

Verifying patient identity

-

Have clear policies in place regarding checking identities. This is of particular importance when there are prescription requests that could indicate a safeguarding concern such as for addictive drugs or for recurrent sexually transmitted infections.

Safe prescribing

- Have clear safe prescribing policies in place, especially regarding drugs with the potential for misuse as well as addiction.

- Have clear policies in place regarding checking identities, especially when there are prescription requests that could indicate a safeguarding concern such as for addictive drugs or for recurrent sexually transmitted infections.

Organisational safeguarding lead

- Have a organisational safeguarding lead.

- Ascertain who safeguarding advice can be sought from when needed and have this information easily accessible to all staff members. This includes seeking advice from within the organisation and from external safeguarding professionals.

- Ascertain whether the organisational safeguarding lead can be part of any local peer support networks such safeguarding lead forums.

Safeguarding documentation and information sharing

- Information sharing is fundamental to safeguarding children and adults. Those working in the independent sector should have an understanding of the multi-agency process of information sharing when there are safeguarding concerns and how they will ensure they are included in this process. For example, when there is a concern that a child or adult is being abused or neglected, multi-agency partners need all the relevant information from health services to be able to make safe and accurate decisions about that child or adult’s welfare. Local authorities will generally request relevant information from NHS health partners such as GPs, health visitors, midwives, mental health trusts and hospital trusts. Independent providers should consider how they can ensure that the information they hold can be part of the multi-agency safeguarding process and response.

- Ensure safeguarding concerns are documented clearly in the patient record including appropriate safeguarding coding and flags on records so that when there are safeguarding concerns, these are immediately identifiable to any clinician caring for the patient.

- Professionals and providers should seek consent to share information wherever appropriate to do so but also be aware of their responsibility to share information without consent when necessary to do so, particularly when there are safeguarding concerns.

- If a patient does not want to share information with their NHS GP or other healthcare providers, this should be fully explored to understand the reasons for this.

- Safeguarding relies on appropriate and effective communication between different healthcare providers. Providers should therefore ensure there is good communication and information sharing between independent GPs and other independent sector staff and between NHS sector staff including NHS GPs, hospital staff and social care. This is a professional responsibility and placing the onus on patients to do this is inappropriate.

Think family approach

- Make children visible and use a 'think family' approach in consultation. Have conversations with the parents that discuss their children at an early stage in the doctor patient relationship.

- Understand the constraints of seeing families and children with limited access to full information and think about asking for more contextual information if necessary to support your 'think family' approach.

Further resources

- CQC. GP mythbuster 25: Safeguarding adults at risk. Updated 2024.

- CQC. GP mythbuster 33: Safeguarding children. Updated 2024.

References

- GMC. Protecting children and young people: The responsibilities of all doctors.

- Kingston and Richmond Safeguarding Children Partnership. Safeguarding in Affluent Communities.

- Professor Claudia Bernard. Goldsmiths, University of London. An Exploration of How Social Workers Engage Neglectful Parents from Affluent Backgrounds in the Child Protection System.

- CQC. The state of care in independent online primary health services. Findings from CQC’s programme of comprehensive inspections in England.

- FSRH/BASHH. Standards for Online and Remote Providers of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services.2019.

- NHS England Safeguarding App. For practitioners in England, the NHS Safeguarding App is an easy way to find your local authority details. It can be accessed by visiting your device’s appropriate app store and searching for ‘NHS Safeguarding’.

Part 2A: Identification of abuse and neglect

This section covers the identification of abuse and neglect in children and adults. The information contained within this section is taken from a very wide range of sources, with the aim to bring together the key information practitioners need in general practice to be able to identify abuse and neglect.

Identifying child abuse and neglect:

- The rights of children.

- Adverse childhood experiences.

- Safeguarding young people aged 16 and 17 years old.

- Age of consent, Fraser Guidelines and Gillick competence.

- How does child abuse/neglect present in general practice?

- Obstacles to recognising and responding to child abuse and neglect.

- Where do children experience abuse and neglect?

- Contextual safeguarding.

- Children at greater risk of abuse and neglect.

- Children who may be invisible to services.

- Looked after children.

- Caring for refugee and asylum seeking children.

- Perinatal safeguarding.

- Unseen men.

- Disguised compliance.

- Types of child abuse and neglect:

- physical abuse

- bruising in non-mobile infants

- abusive head trauma and persistently crying babies

- perplexing presentations and fabricated or induced illness (FII)

- neglect

- Was not brought

- emotional abuse

- sexual abuse

- talking about child sexual abuse

- working with families affected by child sexual abuse

- online child sexual abuse and exploitation

- child sexual exploitation

- child criminal exploitation and gangs

- harmful sexual behaviour

- Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA)

- child trafficking and modern slavery

- female genital mutilation (FGM)

- child abuse linked to faith or belief

- bullying and cyberbullying.

- physical abuse

Topics covering both child and adult issues:

- Radicalisation.

- Domestic abuse including ‘honour’ based abuse and forced marriage.

- Transitional safeguarding.

Identifying adult abuse and neglect:

- Types of adult abuse and neglect:

- physical abuse

- sexual abuse

- psychological or emotional abuse

- financial or material abuse

- modern slavery

- discriminatory abuse

- neglect and acts of omission

- self-neglect.

- Organisational abuse including safeguarding in care homes.

- Adults at greater risk of abuse and neglect.

- How adult abuse/neglect presents in general practice?

- Safeguarding those who are homeless.

- Was not brought.

The rights of children

The rights of children are enshrined in UK law. The UK ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) in 1992. The Convention has 54 articles that cover all aspects of a child’s life and set out the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights that all children everywhere are entitled to. It also explains how adults and governments must work together to make sure all children can enjoy all their rights.

Every child has rights “without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status.”

—Article 2, UNCRC

There are four articles in the Convention that are seen as special. These are known as the ‘General Principles’. They are:

There are also articles within the Convention’s 54 articles which are particularly relevant to safeguarding and child protection. For example:

- Article 19 (protection from violence, abuse and neglect). Governments must do all they can to ensure that children are protected from all forms of violence, abuse, neglect and bad treatment by their parents or anyone else who looks after them.

- Article 39 (recovery from trauma and reintegration). Children who have experienced neglect, abuse, exploitation, torture or who are victims of war must receive special support to help them recover their health, dignity, self-respect and social life.

A summary by UNICEF of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child can be found here: UNCRC_summary-1_1.pdf.

This summary provides a powerful reminder of the rights of children which should be embedded into all that we do to protect children from abuse and neglect as well as supporting those who are victims and survivors.References

Adverse childhood experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are highly stressful and potentially traumatic events or situations that occur during childhood and/or adolescence. They can be single events, or prolonged threats to (and breaches of) the young person’s safety, security, trust or bodily integrity. These experiences directly affect the young person and their environment, and require significant social, emotional, neurobiological, psychological or behavioural adaption. In other words, ACEs can affect the way young people feel, behave and view the outside world. There are examples of ACEs below.

Experiencing trauma can result in a young person struggling with their mental health. A wide range of mental health conditions and symptoms can be linked to trauma, including, anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders and self-harming behaviours.

ACEs can have a significant negative impact on people’s lives. However, such experiences should not be seen as placing limits on someone’s aspirations and achievements. Individuals’ experience of and response to adversity and trauma depends on a range of factors, including the existence of supportive relationships, positive community experiences, access to financial resources and other forms of support. It’s therefore not possible to determine an individual’s longer-term outcomes (like their health or education) based on the number of ACEs they have experienced.

Scotland’s National Trauma Transformation Programme highlights that “adversity is not destiny”: many people may experience some form of traumatic event in their lives; the majority of people recover well, through supportive, positive relationships with family, friends, colleagues, people in their community, service professionals, and in some cases also receiving clinical psychological interventions or therapy.

Some examples of ACEs:

- Abuse or neglect.

- Violence and coercion, e.g. domestic abuse, gang membership, being a victim of crime.

- Adjustment, e.g. migration, asylum or ending relationships.

- Prejudice, e.g. anti-LGBTQIA+, sexism, racism or disablism.

- Household or family adversity, e.g. substance misuse, intergenerational trauma, destitution or deprivation.

- Inhumane treatment, e.g. torture, forced imprisonment or institutionalisation.

- Adult responsibilities, e.g. being a young carer or involvement in child labour.

- Bereavement and survivorship, e.g. traumatic deaths, surviving an illness or natural accident.

Impact of ACEs

Those who experience four or more ACEs are:

- Two times more likely to binge drink and have a poor diet.

- Three times more likely to be a current smoker.

- Four times more likely to have low levels of mental wellbeing and life satisfaction.

- Five times more likely to have had underage sex.

- Six times more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy.

- Seven times more likely to have been involved in violence.

- 11 times more likely to have used illicit drugs.

- 11 times more likely to have been incarcerated.

Protective factors against ACEs

There are some personal, structural and environmental factors which can protect children against adverse outcomes. Examples of these are:

- Positive and supportive family environments.

- Safe and mutual relationships with peers.

- Access to a wider supportive and understanding community.

- Ability to regulate emotions and manage emotional distress.

- Acquisition of practical problem-solving skills.

- Compassionate, attuned and supportive responses from professionals.

- Early intervention from support, therapeutic or safeguarding services.

- Trauma-informed policies & systems that address bullying, harassment or victimisation.

How can general practice support patients who have experienced adverse childhood experiences?

- Be aware of adverse childhood experiences, how common they are and how they relate to health and wellbeing.

- Be able to recognise the impact, short and long term, of adverse childhood experiences.

- Be trauma informed and embed trauma informed practice routinely into your organisation and professional role. (More information on trauma informed practice is in Section 3 of the toolkit.)

- Be able to respond compassionately and supportively to those who have experienced trauma.

- Be mindful that colleagues may also have experienced adverse childhood experiences.

- Take appropriate safeguarding action when needed.

References

- Young Minds. Understanding Trauma and adversity. 2024.

- Scottish Government. Factsheet:Psychological trauma and adversity including ACEs (adverse childhood experiences). 2024.

- National Trauma Transformation Programme. Home page of NTTP. Responding to Psychological Trauma in Scotland.

Safeguarding young people aged 16 and 17 years old

There are a number of issues to consider in this age group:

- Young people who are 16 and 17 years old have significant potential to fall through the gaps between child and adult services.

- They are still legally children and should be given the same protection and entitlements as any other child.

- The fact that a child has reached 16 years of age, is living independently or is in further education, is a member of the armed forces, is in hospital or in custody in the secure estate, does not change their status or entitlements to services or protection. In Scotland, the definition of a child varies in different legal contexts. Where a young person between the age of 16 and 18 requires support and protection, services will need to consider which legal framework best fits each persons’ needs and circumstances.

- Mental capacity legislation in all UK nations applies from 16 years old.

- Professionals have to balance the rights of young people with their duty to protect them from abuse and neglect.

- No child can ever consent to their own abuse.

- Consider transitional safeguarding.

- Actively prepare, plan and advocate for transition into adulthood including into adult services.

References

- NSPCC. Children and the law. 2024.

- HM Government. Working together to safeguard children. Updated 2024.

Age of consent

In each UK nation, the age at which people can legally consent to sexual activity (also known as the age of consent) is 16-years-old. This is the same regardless of the person's gender identity, sexual identity and whether the sexual activity is between people of the same or different gender.

Sexual activity involving a child under the age of 13 should always result in a child protection referral. This includes situations where both children engaged in sexual activity are under 13 years old and even if the child under 13 has agreed to sexual activity. Anyone under 13 lacks capacity to give valid consent to any sexual act.

The law is there to protect children from abuse or exploitation. It is not designed to unnecessarily criminalise children.

Although children over the age of 16 can legally consent to sexual activity, they may still be vulnerable to harm through an abusive sexual relationship. Practitioners should assess and address their safety and wellbeing in line with safeguarding procedures.

The law gives extra protection to all under 18 year olds, regardless of whether or not they are over the age of consent. It is illegal:

- to take, show or distribute indecent photographs of a child under the age of 18 (this includes images shared through sexting or sharing nudes)

- to sexually exploit a child under the age of 18

- for a person in a position of trust (for example teachers or care workers) to engage in sexual activity with anyone under the age of 18 who is in the care of their organisation.

Regarding sexual activity, the GMC highlights in their guidance: 0-18 years: guidance for all doctors, (paragraphs 57 – 62):

- “A confidential sexual health service is essential for the welfare of children and young people. Concern about confidentiality is the biggest deterrent to young people asking for sexual health advice. That in turn presents dangers to young people’s own health and to that of the community, particularly other young people.

- You can disclose relevant information when this is in the public interest. If a child or young person is involved in abusive or seriously harmful sexual activity, you must protect them by sharing relevant information with appropriate people or agencies, such as the police or social services, quickly and professionally.

- You should consider each case on its merits and take into account young people’s behaviour, living circumstances, maturity, serious learning disabilities, and any other factors that might make them particularly vulnerable.

- You should usually share information about sexual activity involving children under 13, who are considered in law to be unable to consent. You should discuss a decision not to disclose with a named or designated doctor for child protection and record your decision and the reasons for it.

- You should usually share information about abusive or seriously harmful sexual activity involving any child or young person, including that which involves:

- a young person too immature to understand or consent

- big differences in age, maturity or power between sexual partners

- a young person’s sexual partner having a position of trust

- force or the threat of force, emotional or psychological pressure, bribery or payment, either to engage in sexual activity or to keep it secret

- drugs or alcohol used to influence a young person to engage in sexual activity when they otherwise would not

- a person known to the police or child protection agencies as having had abusive relationships with children or young people.

- You may not be able to judge if a relationship is abusive without knowing the identity of a young person’s sexual partner, which the young person might not want to reveal. If you are concerned that a relationship is abusive, you should carefully balance the benefits of knowing a sexual partner’s identity against the potential loss of trust in asking for or sharing such information.”

Fraser guidelines and Gillick competence

These two terms are often used together but there are distinct differences between them.

The Fraser guidelines apply to advice and treatment relating to contraception and sexual health.

Gillick competency is often used in a wider context to help assess whether a child has the maturity to make their own decisions and to understand the implications of those decisions.

Fraser guidelines

Fraser guidelines are used specifically to decide if a child can consent to contraceptive or sexual health advice and treatment. They can also be applied to advice and treatment for sexually transmitted infections and the termination of pregnancy.

Practitioners using the Fraser guidelines to guide care should be satisfied of the following:

- the young person cannot be persuaded to inform their parents or carers that they are seeking this advice or treatment (or to allow the practitioner to inform their parents or carers)

- the young person understands the advice being given

- the young person's physical or mental health or both are likely to suffer unless they receive the advice or treatment

- it is in the young person's best interests to receive the advice, treatment or both without their parents' or carers' consent

- the young person is very likely to continue having sex with or without contraceptive treatment.

Health professionals should still encourage the young person to inform his or her parent(s)/carers or get permission to do so on their behalf, but if this permission is not given they can still give the child advice and treatment. If the conditions are not all met, however, or there is reason to believe that the child is under pressure to give consent or is being exploited, there would be grounds to break confidentiality which may include (depending on the situation) sharing necessary and proportionate information with parents and making a child safeguarding referral.

When using Fraser guidelines for issues relating to sexual health, you should always consider any previous concerns that may have been raised about or by the young person and any potential child protection concerns:

- Underage sexual activity is a possible indicator of child sexual exploitation and children who have been groomed may not realise they are being abused.

- Sexual activity with a child under 13 should always result in a child protection referral.