Women's health toolkit

| Site: | Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment |

| Course: | Clinical toolkits |

| Book: | Women's health toolkit |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 18 January 2026, 6:03 AM |

Description

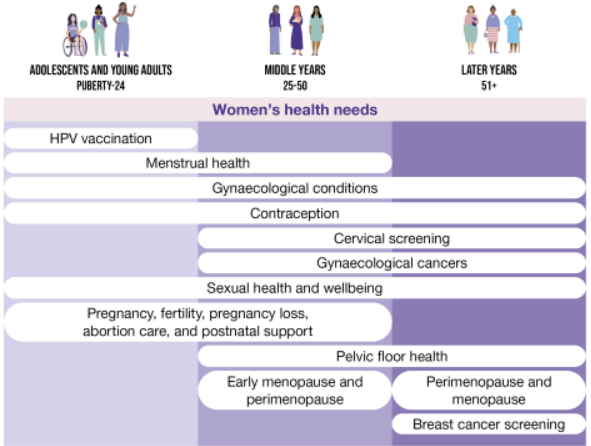

This Women’s health toolkit is categorised into sections best representing the needs of women at different stages of their lives.

In August 2025, the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) became an independent college, the College of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (CoSRH). Where you see FSRH in any of our courses, please read it as CoSRH – updates will be made to the name at the next routine review of each course.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Cervical screening and HPV vaccination

- Menstrual health

- Gynaecological conditions – PCOS and ovarian cysts

- Gynaecological conditions – benign vulval conditions and FGM

- Contraception

- Gynaecological cancers

- Sexual health and wellbeing

- Fertility

- Pregnancy and the postnatal period

- Pregnancy loss and abortion care

- Pelvic floor health

- Menopause

- Breast cancer

- References and resources

Introduction

The 2022 update of the women’s health strategy noted that women spend a significantly greater proportion of their lives in ill health or disability when compared with men, that women are under-represented in clinical trials and that not enough focus is placed on female specific issues such as miscarriage and the menopause.

Proposed actions from the report include the following which are relevant to primary care:

This toolkit aims to provide those working in primary care with a one-stop resource for all their women’s health educational needs – it will cover all stages of a woman’s life, as illustrated in this infographic from the women’s health strategy. The toolkit will signpost to educational materials and relevant guidelines in women’s health, from a variety of organisations. Those interested in learning more should also visit our women’s health library which is a collaboration between the RCGP, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the College of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (CoSRH). Many of the RCGP eLearning courses referred to in this toolkit can be found on the gynaecology and women’s health hub.

Those affected by the conditions covered in the toolkit are all of the female sex and so the words woman/women and the pronouns she/her are used throughout, however some of our patients will have a gender identity which is different to their biological sex. Where this is the case, the patient’s chosen pronouns should be recorded and respected.

Image from the Women’s Health Strategy 2022, used under the Open Government Licence 3.0

Cervical screening and HPV vaccination

The

incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in developed countries has more than

halved in the last 30 years, thanks to cervical screening (now including primary human papilloma virus (HPV) testing), and the advent of vaccination

against HPV. One observational study using data from cancer registries

estimated a relative reduction in cervical cancer of 87% for those aged 12-13

who are vaccinated, compared to an unvaccinated cohort. HPV vaccination is done

in schools, but those who miss their vaccine in school and seek one later can

be vaccinated in primary care up to the age of 25 – those at particularly high

risk can be referred to a sexual and reproductive health clinic for vaccination

up to the age of 45.

There is now a real possibility that cervical cancer may be eradicated – the World Health Organization has set a 90/70/90 target for 2030, whereby 90% of girls are fully vaccinated against HPV by the age of 15, 70% of women have had cervical screening by 35 and 90% of women with pre-cancer or cancer are managed appropriately. The NHS has gone further and aims to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040 - as part of this initiative there will be more flexibility to offer vaccines in convenient places such as libraries and leisure centres, with such premises also offering health checks at the same time as the vaccine.

Cervical screening samples in the UK are now initially tested for HPV; only those which are HPV positive are taken forward for cytology. This has allowed the screening interval to be safely lengthened to five years for all HPV negative women in Wales and Scotland. This page will be updated if England and/or Northern Ireland follow suit. An important exception to this is women with HIV, who continue to need annual smears.

This change to HPV screening does mean that some women will get a letter saying that they have a positive HPV test, but negative cytology, and need a repeat smear test in one year. Some of these women will be concerned that they have a sexually transmitted infection and may phone their GP for advice; those wondering what they would say in such a situation might want to look at the relevant page on the NHS website. Patients who are particularly concerned might want to take advantage of the advice service from the charity Eve appeal. The The RCGP eLearning module on cervical screening provides an update on the current screening process, and cervical screening is also discussed in detail in the RCGP eLearning course on early diagnosis of endometrial and cervical cancer.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Menstrual health

Menstrual disorders are common:

- They make up 12% of all referrals to gynaecology services; many are also managed in primary care.

- The prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in adolescents is up to 37%.

- Over 70% of adolescents experience dysmenorrhoea.

- Severe dysmenorrhoea is reported in up to 29% of women.

- Up to 30% of women experience severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS), with 10% meeting the criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

The impact of menstrual symptoms can be severe – dysmenorrhoea is associated with depression, anxiety, poor quality of sleep and reduced concentration and academic performance for women and girls in education. The 2020 Menstrual Health Coalition report found that stigma about HMB was preventing women from seeking medical help or speaking openly to their employer about the problems that they are facing. This is an area in which health inequalities are important; a 2018 cohort study found that deprivation was associated with more severe symptoms and worse quality of life at the first outpatient visit for HMB. A 2018 report by Plan International UK showed that more than 10% of women in the UK had difficulty with the cost of sanitary products – consider referring to your social prescribing link worker if this may be an issue, as well as letting those still in education know that their schools and colleges should be providing these products under the Period Products Scheme.

Symptoms such as dysmenorrhoea and HMB may be indicative of gynaecological pathology such as endometriosis or fibroids or may be idiopathic. All women need to have their symptoms treated in primary care when they present, and those women in whom there is suspicion of pathology need referral for diagnosis and definitive management of any underlying cause. In the case of HMB, the RCGP eLearning module clearly explains how to risk-stratify women and decide whether referral or empirical treatment is appropriate, a decision that can be made with no vaginal examination or scan, in women where there are no other symptoms and a low risk of pathology. The only test which is mandatory for all women with HMB is a full blood count. Click here to see more about when it is safe to treat empirically. For women with dysmenorrhoea in whom there is suspicion of endometriosis, European guidance states that empirical management in primary care is an equally valid strategy as immediate referral for a laparoscopy – this decision should be made using the principles of shared decision making and might be based on factors such as the woman’s age, severity of symptoms, success of any past treatments, and whether she is trying to conceive. A list of specialist centres for endometriosis can be found here and may be useful to guide referrals.

Premenstrual syndrome is not usually indicative of any underlying pathology, but it can be severe and disrupt daily functioning. Symptoms occur during the luteal phase and abate with or soon after the onset of menstruation – they may be physical and/or psychological. Lifestyle advice and treatment of any dysmenorrhoea or HMB may help and the PMS itself can be treated with an anovulatory contraceptive method such as combined hormonal contraception taken continuously, or with an SSRI with or without CBT.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Resources for commissioning GPs:

Gynaecological conditions – PCOS and ovarian cysts

The RCGP curriculum on gynaecology and breast lists a variety of conditions, many of which are covered in other pages of this toolkit; conditions not covered elsewhere include polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), benign ovarian cysts, benign conditions of the vulva and female genital mutilation (FGM).

When a pelvic scan is requested, it is common for a small ovarian cyst to be reported, which may not be relevant to the reason for the scan and may be a normal variant in the luteal phase. RCOG guidance advises that asymptomatic simple cysts of less than 50mm in a pre-menopausal women do not need any follow-up, with either a repeat scan or a Ca125 test, that those with a diameter of 50 – 70mm should have a repeat ultrasound in one year, and that those larger than 70mm should be considered for MRI or surgery, which from a primary care perspective means that a referral is needed. A cyst that is growing on repeat scan is unlikely to be functional and therefore needs further investigation or referral. It is also worth checking if you have a local pathway, as some of these vary in the cut-off size for investigation/referral and many will recommend repeat scanning earlier than one year. Cysts which are multilocular or have acoustic shadowing or solid components are not simple and secondary care advice should be sought. Post-menopausal women with an ovarian cyst should all have a Ca125 checked and a simple asymptomatic cyst of less than 50mm with a normal Ca125 can be managed with a repeat scan in 4-6 months, but any symptoms or complex features require a specialist opinion.

PCOS is one of the commonest endocrine disorders affecting women of reproductive age; the prevalence may be as high as one in four women, depending on the diagnostic criteria used. Diagnosis requires two out of a possible three criteria – infrequent or no ovulation, clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound scan. A diagnosis can therefore potentially be made with no scan, if the first two criteria are present, and the presence of polycystic ovaries on scan with no clinical features does not mean that the woman has PCOS. Adolescent girls require both of the first two criteria to be present for a diagnosis of PCOS and in any case caution should be used in diagnosing PCOS within the first eight years after the menarche, when irregular cycles are common.

Management of PCOS is largely that of the metabolic risks, with screening advised for cardiovascular risk factors. Obesity and subfertility should be managed according to local pathways and appropriate action should be taken to manage any psychological sequelae. If there is less than one period every three months then there is a risk of endometrial hyperplasia – this can be managed using a combined oral contraceptive, the levonorgestrel intrauterine device, or a short course of a progestogen taken on demand when three months has passed without a period. Metformin is increasingly requested in women with PCOS who do not have diabetes – NICE suggest that we consider specialist advice and also that it may be beneficial in those at higher metabolic risk if lifestyle change does not achieve the required goals. This also fits with the guidance on diabetes prevention which suggests the use of metformin for those with non-diabetic hyperglycaemia who have a deteriorating blood sugar despite intensive lifestyle change, or who cannot participate in intensive lifestyle change, particularly if the BMI is > 35. International guidelines also recommend it for metabolic outcomes. Use of metformin is off-licence and may be associated with gastrointestinal side-effects and reduced vitamin B12 levels.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Gynaecological conditions – benign vulval conditions and FGM

Vulval cancer should be considered in any woman with persistent vulval symptoms, particularly when there is one area which does not respond to topical treatment, or which appears red, white or ulcerated. If there is any concern about malignancy, the patient should be referred for consideration of a biopsy. Idiopathic pruritus vulvae is unusual; an underlying cause can usually be found. Some women will have an inflammatory dermatosis such as lichen sclerosus, lichen planus or lichen simplex, which can cause long-term scarring if not appropriately managed. The vulva may also be affected by systemic skin diseases such as psoriasis. Vulvodynia is defined as ‘vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain, occurring in the absence of relevant visible findings or a specific, clinically identifiable, neurologic disorder’ and can be difficult to manage, often requiring a multi-disciplinary approach which addresses both physical and psychological aspects.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a term used to describe a variety of procedures in which some or all of the female external genitalia is removed, for non-medical reasons, usually in infancy or childhood. Synonyms used in cultures where FGM is prevalent include female circumcision, initiation, sunna, gudniin, halalys, tahur, megrez, khitan and infibulation. It is illegal for an adult to subject a child to FGM in the UK, or to plan to take a child out of the UK for the purposes of FGM; healthcare professionals have a mandatory duty to report any FGM in girls aged under 18 and we should also be alert to softer signs that a girl may be at risk of FGM. These include a family history of FGM in the mother or an older sister, being aware of plans to take a girl to a high-risk country for FGM, or a girl from a culture that practices FGM talking about a long holiday or plans for a ‘special celebration’ to do with ‘becoming a woman’. Police or social services referral is not mandatory for adults with FGM, but a risk assessment should be undertaken using an approved tool – if a risk to the woman’s children is identified then appropriate reporting should be carried out.

Adults may present with a request for repair of FGM done in childhood, or it may be identified opportunistically during a gynaecological examination or a (possibly unsuccessful) attempt to take a smear test. Referral should be made to a clinic with expertise in this area, who may carry out de-infibulation. Screening for hepatitis B/C and HIV is also advised.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Contraception

For a healthy young woman, a contraception consultation might be the first time that she interacts with her GP practice as an adult. More than half of all women using contraception are using a long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) method, but it is often still the case that ‘I want to start the pill’ is used as a shorthand for ‘I need some contraception’. It’s therefore vital that a first contraception consultation allows time to explore what a woman wants from her contraceptive method, and which type of contraception is best for her. The RCGP eLearning module on contraception discusses the first contraception consultation in more detail and uses a case study approach to illustrate how a woman’s priorities might change during her life, as well as giving detailed information on each method and addressing some common urban myths and how to counteract them. Those who wish to obtain extra qualifications, such as the CoSRH diploma or qualification to fit intrauterine devices or implants, can find more information here.

When prescribing contraception, it is important to consider both efficacy and safety. For LARC methods, the efficacy for perfect use and typical use are very similar, as there is little margin for error by the user. This is not the case for methods such as the pill or patch, which require daily or weekly user input – the difference can be significant and is shown on this table.

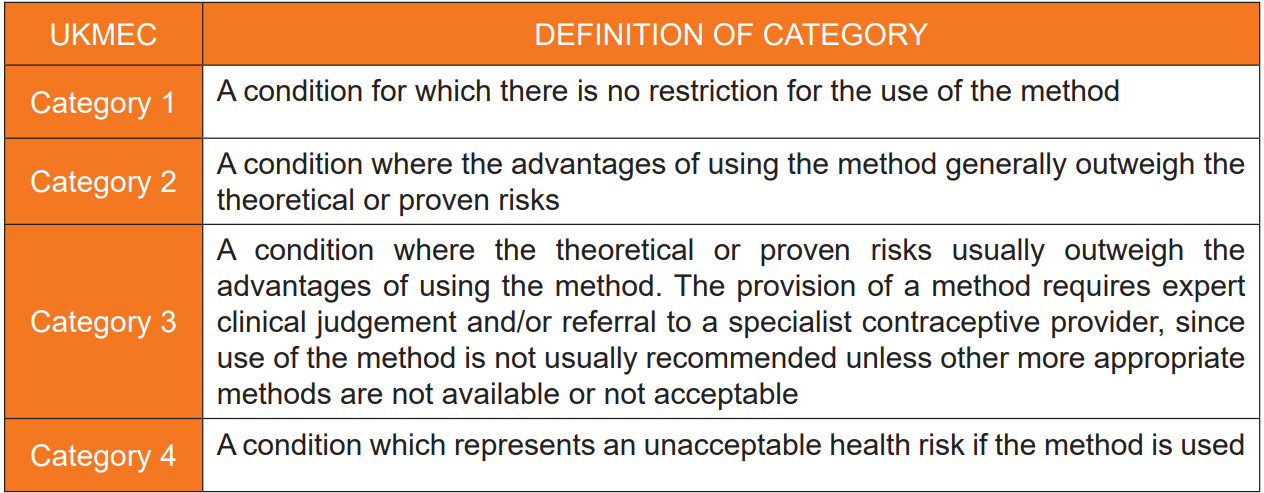

When thinking about safety, the gold-standard reference is the UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use (UKMEC) which classes methods from 1 – 4, as per the table below. This is a situation where two plus two does not necessarily equal four and the UKMEC does not give proscriptive guidance as to how to assess the additive nature of risk factors, leaving this to clinical judgment. It does say that when there are multiple UKMEC 2s relating to the same risk that a different method might be considered, and that if there are multiple UKMEC 3s then the combined risk may be unacceptable. There is also a NICE guidance on LARC.

For more information on the different types of contraception, please see the RCGP eLearning module – the basics are also covered in our two A4 pages of NUBs (‘new and useful bits’) on contraception and specific situations in contraception, which focus on general principles of contraception provision and give more detail than this page. Patient information leaflets on all methods of contraception can be found on the contraception choices website.

For

more detail on the different methods, and providing contraception to particular

groups of

women, or in specific situations, see the guidelines from the Faculty of Sexual

and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH):

Reproduced under licence from CoSRH and the notice Copyright ©Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 2006 to 2016.

Gynaecological cancers

Women can be affected by cancer of the uterus, ovary, cervix, vulva, vagina and Fallopian tube. Symptoms which can indicate a gynaecological cancer may also indicate a benign cause, so a thorough history is always important.

Click on the titles to see risk factors for the various cancers:

More

information can be found in the following resources:

Sexual health and wellbeing

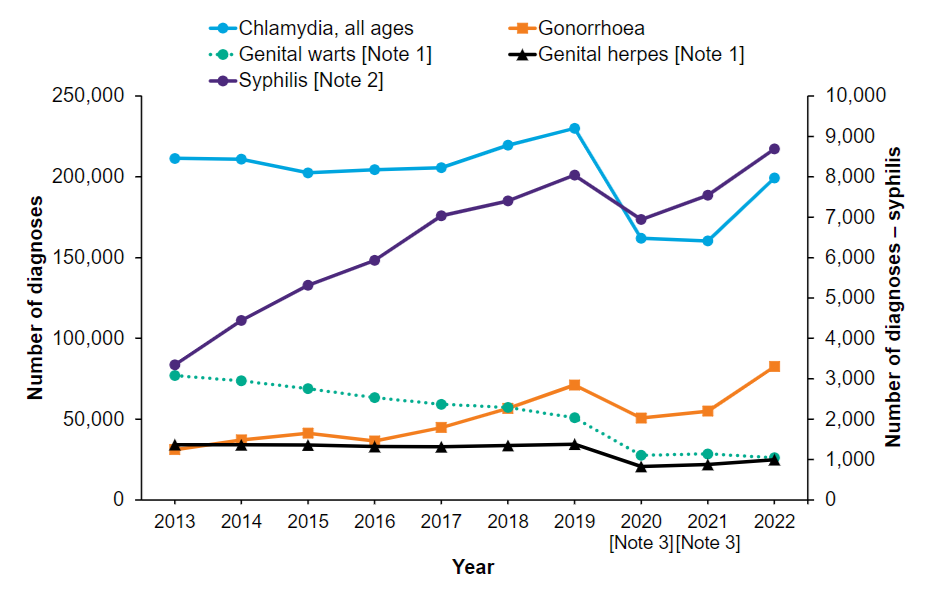

The

incidence of most sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is

increasing

over time,

apart from a reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic. The exception to this

trend is genital warts, which has been falling in incidence since the

introduction of vaccination against human papilloma virus.

The ability to take a sexual history is a key skill in general practice, covered under the sexual health topic of the RCGP curriculum. Patients who attend a sexual health clinic are expecting to be asked about their sexual history, but those attending their GP with gynaecological symptoms may not be expecting this line of questioning and may be embarrassed. If the GP explains that such questioning is routine, and is not embarrassed, then the patient is more likely to be put at ease. Sexual history taking is covered in the RCGP eLearning course on sexual health in primary care – those wanting more detail might look at the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) guideline on sexual history taking.

It is important to always be mindful of issues of safeguarding, particularly for those aged under 16, for whom competence to consent to intercourse should be assessed using the Fraser guidelines. A child aged under 13 cannot legally consent to sex under any circumstances and so this should always be urgently reported to social services.

More detail on individual STIs can be found on the BASHH guidelines page, which also contains guidelines about specific groups of patients, sexual violence and the management of STIs in children and young people.

More

information can be found in the following resources:

Fertility

Infertility is defined by the WHO as failure to achieve a pregnancy after ≥ 12 months of regular (every 2-3 days) unprotected intercourse. 80% of couples in which the woman is aged under 40 will conceive in this timeframe and about half of those who don’t will conceive naturally in the next year.

Infertility can be caused by a variety of factors – the most recent figures for the UK are male factor (30%), ovulatory disorder (25%), tubal damage (20%), uterine or peritoneal disorders (20%) and unexplained (25%) – around 40% of couples have both a male and a female contributory factor and there may be more than one female factor.

Useful advice in primary care would include the avoidance of smoking for both men and women who want to conceive, that women should take folic acid, that an alcohol intake of >14 units/week may damage semen quality and that a body mass index over 30 kg/m2 is likely to reduce fertility in both sexes, as will a body mass index of < 19 kg/m2 in a woman.

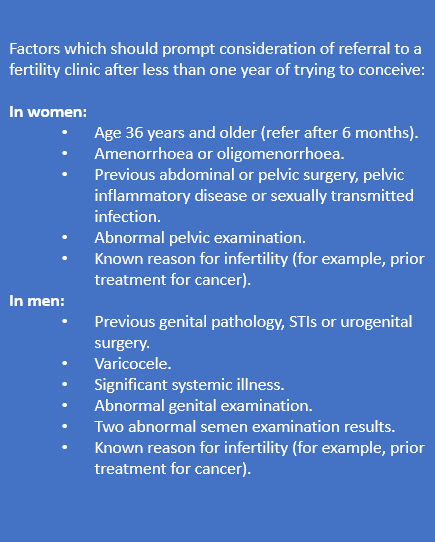

Our

main input into the management of infertility is to recognise it and refer

appropriately, after initial investigations in primary care. NICE advises that

investigation and referral should generally start at one year. Women who are

aged ≥ 36 should be referred after six months, and those who have other factors

which might indicate a cause for subfertility (listed in the box on this page)

should also be considered for earlier referral.

Our

main input into the management of infertility is to recognise it and refer

appropriately, after initial investigations in primary care. NICE advises that

investigation and referral should generally start at one year. Women who are

aged ≥ 36 should be referred after six months, and those who have other factors

which might indicate a cause for subfertility (listed in the box on this page)

should also be considered for earlier referral.

Eligibility criteria for fertility treatment will vary by area and may include consideration of age, BMI, smoking status and existing children in the current relationship or with previous partners. A list of investigations is also usually expected at the time of referral – these may include FBC, rubella immunity, tests for hepatitis B/C and HIV, a basic hormone screen, chlamydia test, pelvic ultrasound and semen analysis.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Pregnancy and the postnatal period

Antenatal and intrapartum care have become much more the domain of secondary care over the last few decades. Only 2% of births take place at home and the concept of the ‘obstetric flying squad’ is now historical, with the understanding that it is safer to transport women who are having obstetric complications to a hospital, rather than trying to bring the hospital to the woman. We will however see pregnant women who present with new symptoms, or a worsening of existing medical conditions, some of whom will be at a high-risk of pregnancy-related complications. We also need to consider the risk:benefit balance when prescribing in pregnancy, as many medicines are not licensed for pregnant women. The cohort of women who are having babies is, on average, older than in the past - the number of women who are pregnant in their 40s has doubled since the 1990s. An increasing number of pregnant women have multimorbidities, with one registry study showing that nearly one-quarter of pregnant women had multimorbidities which were active in the year before delivery. Significant issues include obesity, mental health problems and pre-existing cardiac disease, which were relevant to 82%, 25% and 10% of maternal deaths in the last MBRRACE-UK report respectively.

Management in the post-natal period is largely done in primary care – this is a risky time for a woman, with the risk of venous thromboembolism being higher in the early post-natal period than during pregnancy. 52% of maternal deaths occur between 1 and 41 days after delivery. Whilst the risk from physical health decreases significantly as time passes, the same cannot be said for mental health risks; the 2023 MBRRACE-UK report showed that nearly 40% of deaths from mental health related causes occurred between six weeks and one year after the end of pregnancy. The professional carrying out a woman’s post-natal check should always specifically enquire about mental health. We are also responsible for the 6-8 week baby check, which may pick up significant health issues and for prescribing to breastfeeding women, where drug licences are often also notable by their absence.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Pregnancy loss and abortion care

A woman who fears that she is losing her pregnancy in the first trimester may present first to the GP; whilst her medical management will be carried out in hospital, our empathetic approach is important and may be remembered long after the event. Women will also come back to primary care after a later miscarriage or a stillbirth for management of any ongoing related physical or mental health issues. Some women will miscarry due to a thrombophilia such as antiphospholipid syndrome; referral for investigation of this should be done after one miscarriage at ≥ 10/40, three miscarriages at < 10/40 or one premature birth at ≤ 34/40.

Women who have a miscarriage before 24/40 are not entitled to any maternity pay and will therefore need a fit note if they are not able to return to work straight away, whereas those who have a miscarriage or stillbirth at ≥ 24/40 are usually entitled to maternity leave in the same way as if they had delivered a live baby. They may also be entitled to parental bereavement leave – if a patient is finding these issues difficult to navigate then referral to a social prescribing link worker may be useful.

Not every woman is happy to be pregnant; our language should be cautious when a woman discloses an early pregnancy, and it isn’t clear whether she wants to continue with it. In most cases, the involvement of primary care in termination of pregnancy is limited to passing on the contact details of the locally commissioned provider, but in some areas, services may be commissioned such that GPs also sign the form HSA1 as the first of two doctors to approve the termination. Those GPs who have a conscientious objection to any involvement in the process must make arrangements for the patient to see another suitably qualified colleague and cannot opt out of treatment necessary to save a life or prevent grave injury. Women in England and Wales can now access a medical abortion at home, after the legal provisions for this during the pandemic were made permanent in August 2022.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Pelvic floor health

Pelvic organ prolapse is common, affecting 10% of women over the age of 50, but many will be asymptomatic. Presentation may be with a feeling of heaviness/dragging, or with urinary or faecal incontinence. Risk factors include multiparity, vaginal or instrumental deliveries, raised BMI, persistent constipation or cough and being post-menopausal. Management may be entirely in primary care, using pessaries and vaginal oestrogen, or may involve referral for consideration of surgery. Some women may have concerns relating to publicity around complications related to the previous use of vaginal mesh devices in prolapse surgery – they can be reassured that this is no longer routinely used in the UK. Any woman presenting with complications from previous mesh use should be referred to a regional MDT centre to assess the risks and benefits of partial or complete removal of the mesh.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Menopause

The menopause is the biological stage in a woman’s life when menstruation stops permanently, due to the loss of ovarian follicular activity. It is diagnosed clinically 12 months after the last menstrual period. Before that, the perimenopause is a time of irregular cycles and fluctuating hormone levels, often accompanied by vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats), as well as other symptoms of the menopause. The average age of the menopause in the UK is 51 years – an early menopause is one that occurs at less than 45, and premature menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is that which occurs below the age of 40. Post menopausal women are at an increased risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and genitourinary syndrome of the menopause (GSM) and those with POI are also at increased risk of all-cause mortality, depression and type 2 diabetes when compared with women who have their menopause at the usual time.

The use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to treat the menopause and perimenopause has fluctuated over the years, often in response to press reports of studies to do with risks such as breast cancer. Many of these studies looked at populations who are very different from women in the UK who use HRT, such as the Women’s Health Information (WHI) study, whose participants had an average age of 63 when they started HRT, using regimes that are now rarely used in the UK. We now know that the use of HRT does not increase mortality from breast cancer and that the absolute number of increased cases is small, and only seen in women using combined HRT. A woman’s risk of breast cancer is increased much more if she has obesity than if she uses HRT but has a normal BMI.

Click here to see two NUBs (‘new and useful bits’) on HRT and menopause which summarise some of the key issues to do with the menopause and the use of HRT, including some basic information about the risk of breast cancer and venous thromboembolism (VTE). In general, women who have had breast cancer in the past should not be prescribed systemic HRT without a specialist opinion, and those who are at an increased background risk of VTE should use transdermal rather than oral HRT, as transdermal preparations do not increase the risk of VTE.

More information can be found in the following resources:

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is managed in secondary care and GPs are not involved in the organisation of screening mammograms; however, we will see patients with symptoms that may be cancer, and those who are worried about their family history of breast cancer. The subject may also come up when discussing contraception and HRT, if women are concerned about an increased risk of breast cancer.

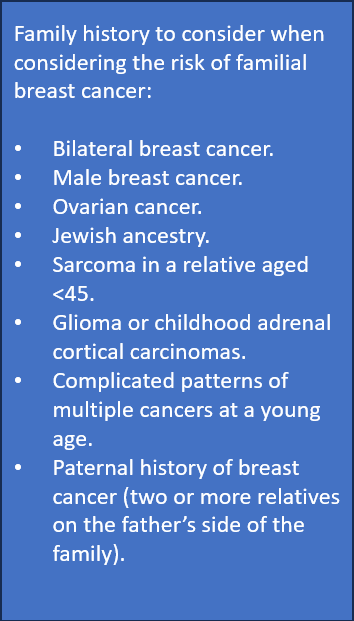

Having a family history of breast cancer is a risk factor for developing the disease, but specific mutations account for only 5% of breast cancers. Most women, including most women with a family history, will have a sporadic breast cancer rather than one caused by a gene such as BRCA1 or BRCA2. The NICE guidance on familial breast cancer is a useful resource when deciding whether to refer. It requires a detailed family history and gives a list of factors which should be enquired about when assessing risk. In general, if a woman has only one first or second degree relative who was diagnosed with breast cancer over the age of 40 and has none of the extra features listed in the box, then their risk of breast cancer is no greater than population risk and there is no need for referral to a genetics clinic. Women who meet the NICE criteria for referral and are assessed at a genetics clinic may be offered regular screening, prophylactic surgery, or prophylactic treatment with tamoxifen or anastrozole, to reduce breast cancer risk.

More information can be found in the following resources:

References and resources

RCGP eLearning

Other RCGP resources

British Menopause Society

FSRH

NICE CKS pages

NICE guidelines

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

RCOG, RCPsych, RCoA and RCPCH resources

Primary care women’s health forum

ESHRE

Patient support groups/charities and patient information leaflets

Government publications and web pages

NHS

NHS England

Cancer Research UK

Other resources and references

Academic papers