_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

World Parkinson’s Day takes place every year on 11th April. Parkinson’s UK is using this year’s event to highlight the realities of living with Parkinson’s disease, helping patients to feel more understood1.

World Parkinson’s Day takes place every year on 11th April. Parkinson’s UK is using this year’s event to highlight the realities of living with Parkinson’s disease, helping patients to feel more understood1.

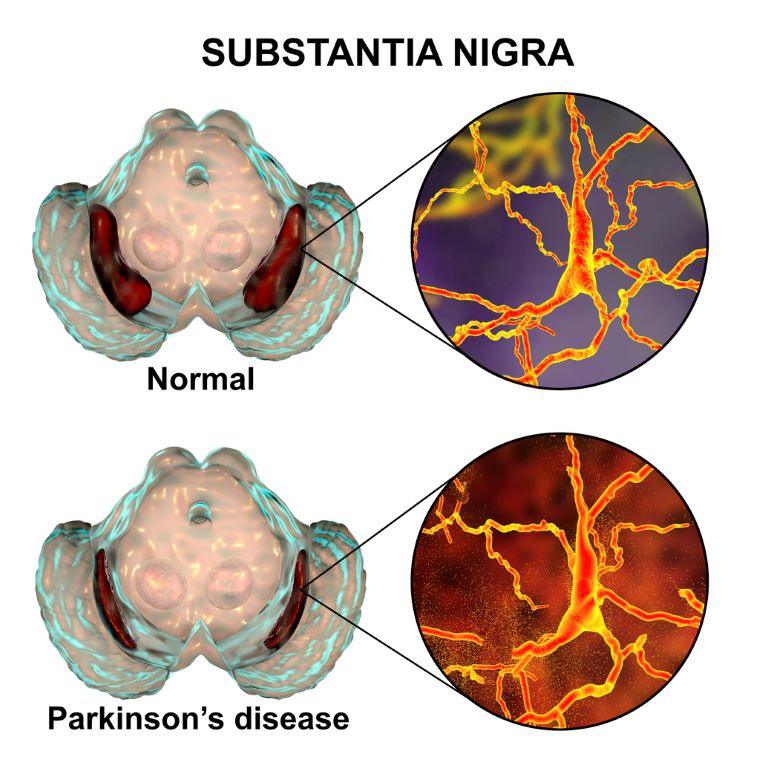

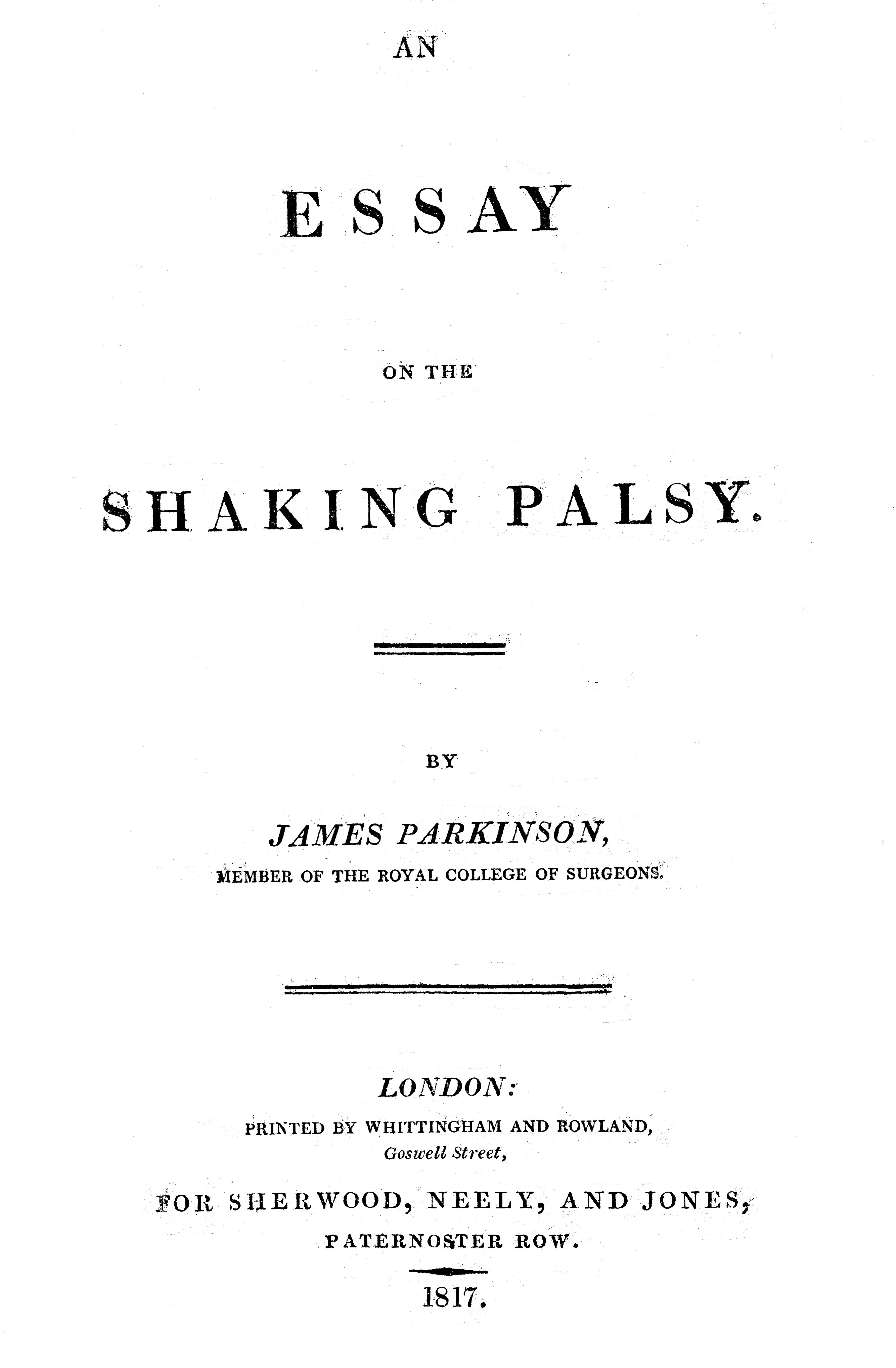

Parkinson’s disease was first described in ‘An essay on the shaking palsy’, written by Dr James Parkinson, an English physician and surgeon, in 18172. This paper established Parkinson’s disease as a recognised medical condition, which NICE defines as: “a progressive neurodegenerative condition resulting from the death of dopamine-containing cells of the substantia nigra in the brain”3. The substantia nigra pars compacta plays an important role in controlling the body’s movement and coordination, in conjunction with the caudate nucleus and putamen.

Parkinson’s is one of the most common neurological conditions and it’s estimated that it affects up to 16 people per 10,0003. According to a report by Parkinson’s UK, the estimated prevalence in the UK for 2018 was 145,519. The charity also found that prevalence was 1.5 times higher in men than in women within the 50-89 age group. In terms of incidence, Parkinson’s UK estimates that approximately 1 in 37 people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s at some point in their lifetime. They predict that the prevalence of the disease will rise by 18% between 2018 and 2025, due to population growth and an increasingly ageing population4.

Typical presentations of Parkinson’s disease include symptoms and signs described as ‘Parkinsonism’: bradykinesia (slow movements), rigidity (abnormal stiffness), resting tremor (typically ‘pill rolling’) and postural instability (loss of balance)1. These symptoms are typically asymmetrical2.

Rigidity can present in different forms including lead-pipe (sustained rigidity, where the limb is heavy and resistant to passive movements) and cogwheel (intermittent rigidity, where the limb moves with jerky and ratcheting motions)5. A ‘pill rolling’ tremor is often seen and is so named because it looks like the patient is rolling a pill between their thumb and index finger. It occurs at rest and can often be alleviated by moving the affected limb. A resting tremor can also occur in other parts of the body such as the legs and lips5. Postural instability is a major reason why people with Parkinson’s disease are at risk of falls: Parkinson’s affects the basal ganglia, which have an inhibitory action on movement. Releasing this inhibition requires the release of dopamine, so the deficiency results in hypokinesia. Freezing gait can also contribute to falls as it can cause patients to stop involuntarily when walking. They may then find themselves unable to initiate movement for several seconds/minutes5. In addition, basal ganglia control balance through cortico-spinal pathways, including auto-adjustment of posture to maintain stability, so reflexes which try to prevent falling are significantly impacted.

Examples of bradykinesia and rigidity include2:

- reduced arm swing

- shuffled gait

- softened voice

- decreased blink rate and facial expression.

Non-motor symptoms include2:

- fatigue

- autonomic dysfunction

- sleep disturbance.

It’s important to note that some conditions may look like Parkinson’s disease. For example, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy or extra-pyramidal side effects of drugs, such as antipsychotics or antiemetics can cause Parkinsonian features3.

Parkinson’s disease is usually diagnosed in secondary care, so any suspected cases should be referred to a neurologist to be seen within 6 weeks3. There are no laboratory or imaging tests that can offer a definitive diagnosis, so diagnosis is usually made based on a detailed clinical history and examination3,6. A specialist in secondary care may use the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank Criteria to assist with diagnosis6.

Parkinson’s disease is usually diagnosed in secondary care, so any suspected cases should be referred to a neurologist to be seen within 6 weeks3. There are no laboratory or imaging tests that can offer a definitive diagnosis, so diagnosis is usually made based on a detailed clinical history and examination3,6. A specialist in secondary care may use the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank Criteria to assist with diagnosis6.

The majority of management is in secondary care and it is recommended that patients receive a follow up every 6-12 months with a specialist who monitors treatment and progression of the condition. Patients with Parkinson’s disease are usually assigned to a Parkinson’s Disease Nurse Specialist (PDNS) who can co-ordinate care with the patient, carer, GP and specialist6. Patients should also be given access to occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech therapy - depending on the severity of their symptoms - to assist with their independence and safety6.

Medication is initiated in secondary care and can be prescribed by the GP after this, in accordance with the local shared care guidelines. Occasionally GPs may be involved with monitoring medication, in liaison with the PDNS6. The following medications are common pharmacological treatments for Parkinson’s disease:

Levodopa

This is a dopamine precursor that converts to endogenous dopamine in the brain. Itis offered to patients in the early stages of the disease, where motor symptoms are already having an impact on their quality of life3,6. Levodopa is considered the core medication in treating Parkinson’s, but it requires close monitoring to get the dosage right. If the dosage is too high, it can result in hallucinations and psychotic behaviour. As the disease progresses and higher doses are needed, adverse effects of levodopa, such as dyskinesias, are more common. Adjusting the dosage, timing and type of preparation can help to manage these effects6.

Dopamine agonists

Another treatment option is the use of drugs that have a dopamine-like action. These stimulate dopamine receptors in the brain and can be used on their own or with levodopa. Patients are likely to experience less long-term side effects from dopamine agonists, but they can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness and sickness if not introduced gradually. Older patients may experience hallucinations. A small percentage of Parkinson’s patients may experience impulsive and compulsive behaviour when taking dopamine agonists. These patients may also be more prone to ‘dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome’ when their treatment is stopped or reduced6.

Other key medications in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease include MAO-B inhibitors and COMT inhibitors. The NICE guidance on Parkinson’s disease in Adults (NG71) and the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on Parkinson’s disease provides more information on these, as well as more comprehensive lists of Parkinson’s medications and possible side effects.

Some medications may be contraindicated as they may cause worsening of the disease by antagonising dopamine receptors. As mentioned before, antipsychotics and anti-sickness drugs can cause extra-pyramidal side effects. These drugs can increase the severity of the Parkinsonian symptoms, particularly rigidity and bradykinesia, and sometimes irreversibly. A list of drugs to avoid can be found in the ‘drug treatments’ section of the Parkinson’s UK website.

GPs are a great source of support for patients with Parkinson’s disease, along with their family members and carers. Through support from their GP, patients are encouraged to take part in decision making and judgements about their own care. As Parkinson’s can affect a patient’s cognition and communication, NICE recommend that any information that is communicated throughout their disease should be given both verbally and in written form3. Family members and carers should also be kept informed about the patient’s condition, advised about their entitlements as a carer, encouraged to request a carer’s assessment from the local authority, and signposted to support services3. As mentioned earlier on, patients with Parkinson’s disease can be prone to falls due to their hypokinesia and balance impairment, so GPs will need to bear this mind when managing other medical conditions connected to falls, such as blood pressure. Orthostatic hypotension is common in Parkinson’s so extra care is needed when prescribing antihypertensives.

As a patient’s disease progresses, GPs are advised to be vigilant to any cognitive impairment. Parkinson’s is associated with Lewy body dementia and if this is suspected, referral to a consultant in older person’s mental health is recommended. As with any chronic disease, GPs should also look out for any signs of depression and screen for this intermittently. Signs of depression may be harder to detect due to the impaired facial expression and verbal difficulties that patients with Parkinson’s disease can experience.

To find out more about Parkinson’s disease and the GP’s role, RCGP members can benefit from access to the following online resources:

EKU6 - Diagnosis and Management of Parkinson's Disease

EKU12 - The Professional's Guide to Parkinson's Disease

References

1 Parkinson’s UK, 2019. Parkinson’s is. [Online] Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/get-involved/parkinsons-is

2 British Medical Journal, 2018. BMJ Best Practice – Parkinson’s disease. [Online] Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/147

3 NICE, 2017. Parkinson’s disease in adults (NG71). [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71

4 Parkinson’s UK, 2018. The incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s in the UK report. [Online] Available at:https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/incidence-and-prevalence-parkinsons-uk-report

5 Parkinson's Europe, 2017. Motor symptoms. [Online] Available at: https://parkinsonseurope.org/signs-and-symptoms/symptoms/

6 Guidelines, 2012. The GP’s guide to Parkinson’s – by Parkinson’s UK. [Online] Available at: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/neurology-/the-gps-guide-to-parkinsons/453864.article

'An essay on the shaking palsy by James Parkinson' image from Wellcome Collection.