_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

The presenting symptom of ‘dizziness’ is very common in primary care and vertigo is one of the two most common causes. A review of five studies of dizziness presentations showed around a third were found to have vertigo, with the prevalence increasing with age.2

The presenting symptom of ‘dizziness’ is very common in primary care and vertigo is one of the two most common causes. A review of five studies of dizziness presentations showed around a third were found to have vertigo, with the prevalence increasing with age.2

Vertigo is a symptom, not a condition in itself.2 It is a false sensation of a person or their surroundings moving or spinning, but with no actual physical movement1. It can be abrupt in onset and aggravated by head movements.1 The first step in making a diagnosis is to find out what the patient means by ‘dizzy’ and whether or not this represents vertigo.

Vertigo is commonly caused by a problem with the inner ear (peripheral vertigo) or the brain (central vertigo)3. Types of peripheral and central vertigo are as follows:

Peripheral3:

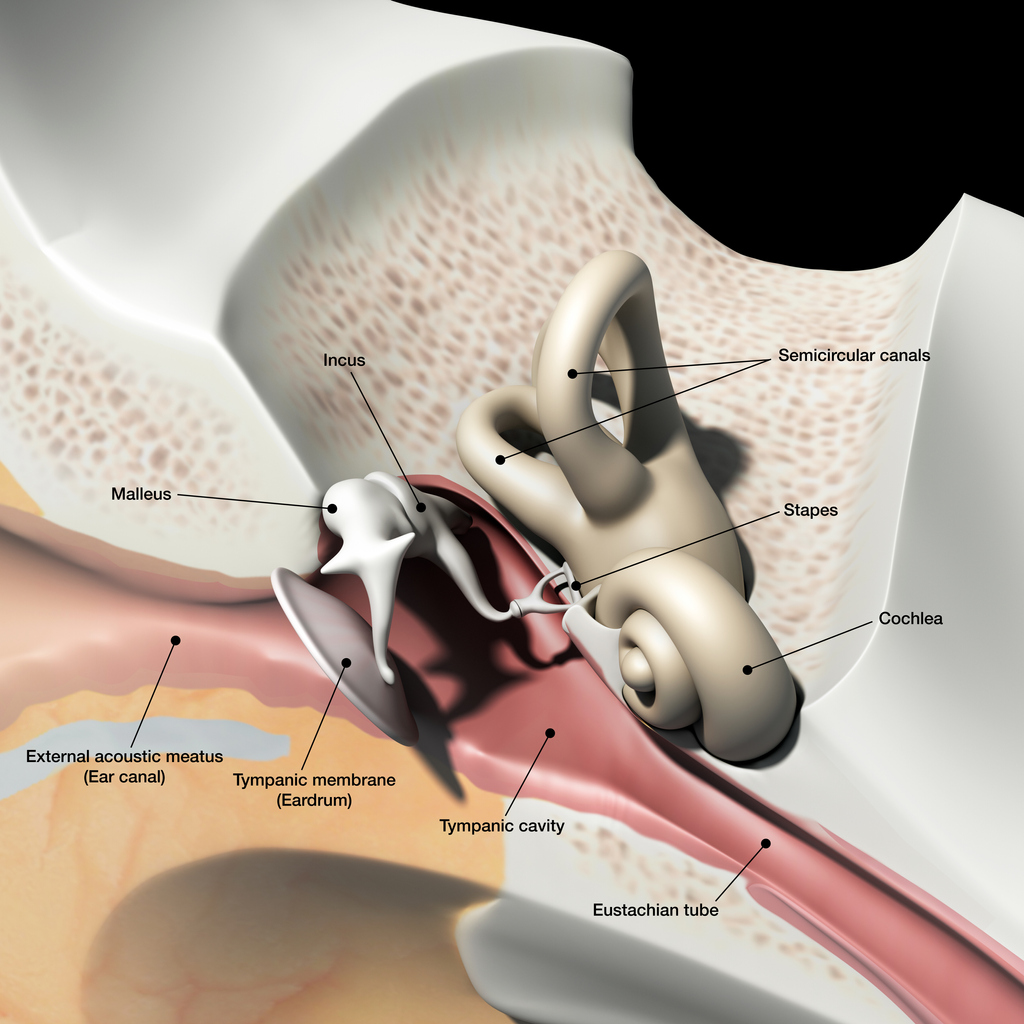

Peripheral vertigo is a group of disorders or dysfunction of the vestibular labyrinth, semicircular canals or the vestibular nerve.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a type of peripheral vertigo and the most common cause of vertigo in general. BPPV involves short, intense, recurrent attacks, often accompanied by nausea. These attacks can last for several minutes or hours. BPPV develops when otoliths become detached from the utricular macula and migrate into one of the semicircular canals. Following head movement, otoliths are stimulated as they are move through the endolymph in the semicircular canals. The stimulation stops as movement ceases. When an otolith is detached, it may continue to move despite the head stopping. The sensation of ongoing movement which comes from the otolith conflicts with other sensory input, such as that from the eyes or proprioception, causing vertigo8.

Vestibular neuronitis is another inner ear condition that triggers symptoms of vertigo. It is almost always caused by a viral infection, which results in inflammation of the vestibular nerve. Symptoms of vestibular neuritis come on suddenly and can cause unsteadiness, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms usually last a few hours or days but can take up to six weeks to resolve completely.

Vestibular neuronitis and labyrinthitis are often used interchangeably, but in neuronitis only the vestibular nerve is inflamed; in labyrinthitis the labyrinth is affected as well. Vestibular neuritis is a very common cause of vertigo, labyrinthitis is much rarer, and because the cochlea is invariably involved, there is always some degree of hearing loss in labyrinthitis.

Ménière’s disease is a rare inner ear disorder which can cause vertigo. Along with tinnitus and hearing loss, patients experience sudden attacks of vertigo which can last for around two to three hours. These symptoms may take a couple of days to completely disappear.4 It is thought that Ménière’s disease is caused by a raised volume of fluid in the labyrinth, which causes distension. This can cause damage to, and thus dysfunction of, the vestibular system and the cochlea.9

Central2:

Central vertigo results from a disorder or dysfunction or the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, or brain stem.

Migraines are the most common cause of central vertigo. Vestibular migraines can cause ataxia, visual disturbances, occipital pain, nausea and vomiting.

Other less common causes of central vertigo include stroke and transient ischaemic attacks, brain tumours, multiple sclerosis and acoustic neuroma.

According to the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on Vertigo, the assessment of a person presenting with vertigo should consist of the following:

- description of the vertigo

- associated symptoms

- relevant medical history – including ear infections, migraine, head trauma and cardiovascular risks.

To distinguish between peripheral or central vertigo on examination, you can perform a rapid head impulse test. This test demonstrates the function of the peripheral vestibular system. If the test is abnormal, peripheral vertigo is suspected and if it is normal, central vertigo is suspected1,3.

The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre can also be used to determine a diagnosis of BBPV in patients with positional vertigo. This test reproduces the patient’s vertigo and possible nystagmus to determine which ear is abnormal and therefore causing the condition.

Treating central vertigo usually starts with treating the migraine, as this is the most common cause. This should usually relieve the vertigo symptoms5. If primary care treatments fail to treat these symptoms or a more serious pathology is suspected, referral to secondary care is recommended4. The urgency of the referral depends on the severity of the symptoms and what may be causing them2.

For peripheral vertigo, canalith repositioning procedures (CRPs) can be used to treat people with BPPV. It focuses on moving the dislodged otoconia back to their correct place in the ear6.

For peripheral vertigo, canalith repositioning procedures (CRPs) can be used to treat people with BPPV. It focuses on moving the dislodged otoconia back to their correct place in the ear6.

Epley manoeuvre: If the patient has positional vertigo and a positive Dix-Hallpike test, the Epley manoeuvre is indicated. It focuses on moving the otoconia back into the saccule. It can also be performed immediately after diagnostic tests and can be repeated if necessary to relieve symptoms. 74% of patients have total resolution of their symptoms within a week of the manoeuvre1. View a diagram and step by step.

Brandt-Daroff: This is recommended if CRPs are ineffective or not suitable. Brandt-Daroff is a treatment for BPPV that can be performed at home without supervision. The repetitive movements encourage the otoconia to move back to their correct position in the inner ear. Discover a step by step of the Brandt-Daroff exercises.

Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises: Management of the underlying cause of the vertigo is the first line treatment. However exercises such as Cawthorne-Cooksey are a form of vestibular rehabilitation which promote central compensation for vestibular dysfunction and offer treatment for chronic vertigo. Doing this may make the dizziness symptoms worse for a few days after the exercises, but perseverance may help to alleviate the symptoms over time6. View step by step instructions. BPPV and Ménière’s disease may not respond well to vestibular rehabilitation.

Medication is generally not recommended to treat vertigo. If a patient is waiting to be admitted to hospital or seen by a specialist, NICE recommend prescribing short-term symptomatic drug treatment to relieve symptoms of nausea and vomiting2. This is recommended for both central and peripheral vertigo if the patient is experiencing severe symptoms. To relieve severe symptoms rapidly, NICE suggest giving the patient buccal prochlorperazine, or a deep intramuscular injection of prochlorperazine or cyclizine. For less severe symptoms, short-term oral courses of vestibular sedatives, such as prochlorperazine, or cinnarizine, cyclizine, or promethazine teoclate (antihistamines) are recommended2. These vestibular sedatives help to suppress the receptors in the semi-circular canals of the inner ear and therefore reduce vestibular hyperactivity. These sedatives can ease the symptoms of dizziness and vomiting that vertigo can cause, but are not a long-term solution as they prolong the body’s readjustment after an instance of vertigo7.

References

1 Molnar A., et al. 2014. Diagnosing and Treating Dizziness. Medical Clinics, Volume 98, Issue 3, 583 – 596. Available at: https://www.medical.theclinics.com/article/S0025-7125(14)00029-7/fulltext

2 NICE. 2017. Clinical Knowledge Summary. Vertigo. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/vertigo

3 Northwestern University Emergency Medicine blog. 2018. Vertigo: A hint on the HiNTs exam. [Online] Available at: https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hints

4 NHS Inform. 2019. Meniere’s disease. [Online] Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/menieres-disease

5 NHS Inform. 2019. Vertigo. [Online]. Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/vertigo

6 Brain and Spine Foundation. 2017. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises. [Online] Available at: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/our-publications/our-fact-sheets/vestibular-rehabilitation-exercises/

7 ENT UK. 2017. Vertigo. [Online] Available at: https://www.entuk.org/vertigo

8 Payne, J. 2016. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo [Online] Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/benign-paroxysmal-positional-vertigo-pro

9 Henderson, R. 2015. Ménière’s Disease [Online] Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/menieres-disease-pro