_ RCGP Learning

User blog: _ RCGP Learning

The presenting symptom of ‘dizziness’ is very common in primary care and vertigo is one of the two most common causes. A review of five studies of dizziness presentations showed around a third were found to have vertigo, with the prevalence increasing with age.2

The presenting symptom of ‘dizziness’ is very common in primary care and vertigo is one of the two most common causes. A review of five studies of dizziness presentations showed around a third were found to have vertigo, with the prevalence increasing with age.2

Vertigo is a symptom, not a condition in itself.2 It is a false sensation of a person or their surroundings moving or spinning, but with no actual physical movement1. It can be abrupt in onset and aggravated by head movements.1 The first step in making a diagnosis is to find out what the patient means by ‘dizzy’ and whether or not this represents vertigo.

Vertigo is commonly caused by a problem with the inner ear (peripheral vertigo) or the brain (central vertigo)3. Types of peripheral and central vertigo are as follows:

Peripheral3:

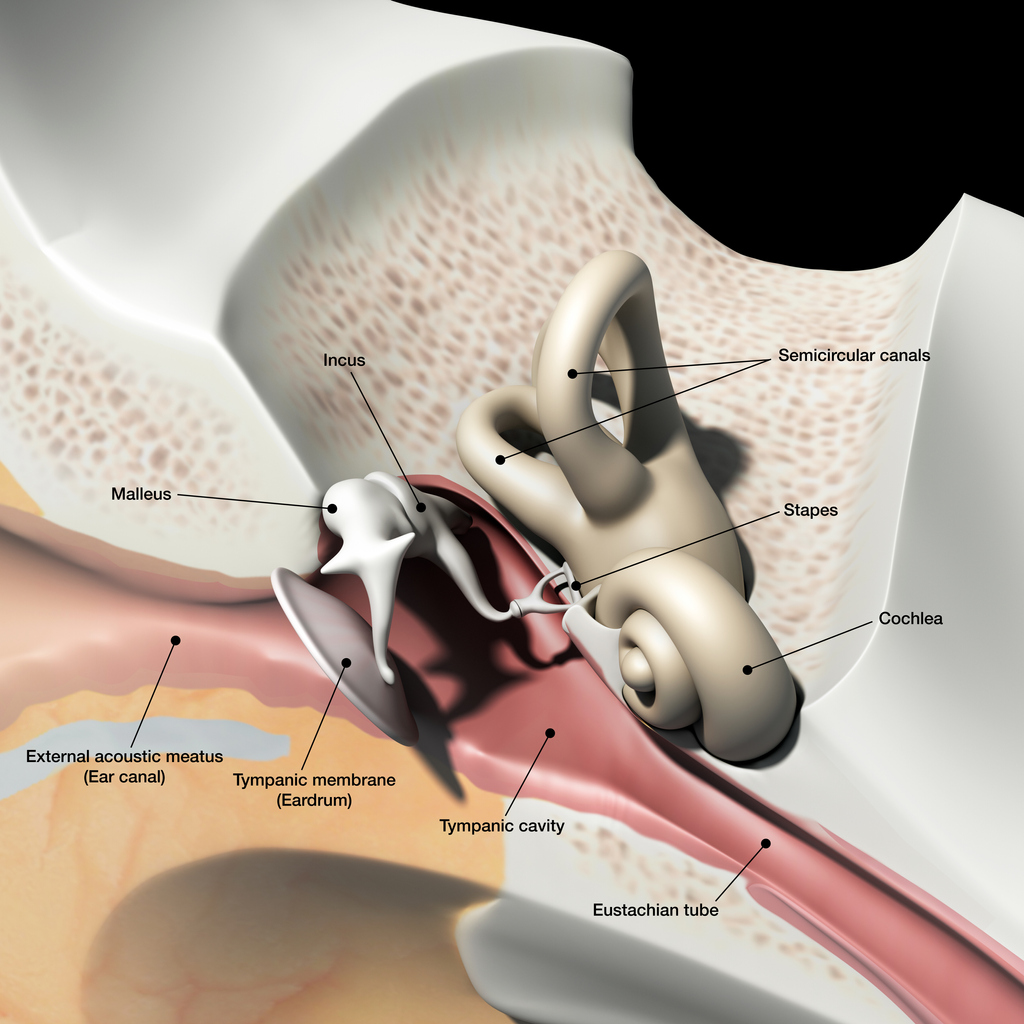

Peripheral vertigo is a group of disorders or dysfunction of the vestibular labyrinth, semicircular canals or the vestibular nerve.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a type of peripheral vertigo and the most common cause of vertigo in general. BPPV involves short, intense, recurrent attacks, often accompanied by nausea. These attacks can last for several minutes or hours. BPPV develops when otoliths become detached from the utricular macula and migrate into one of the semicircular canals. Following head movement, otoliths are stimulated as they are move through the endolymph in the semicircular canals. The stimulation stops as movement ceases. When an otolith is detached, it may continue to move despite the head stopping. The sensation of ongoing movement which comes from the otolith conflicts with other sensory input, such as that from the eyes or proprioception, causing vertigo8.

Vestibular neuronitis is another inner ear condition that triggers symptoms of vertigo. It is almost always caused by a viral infection, which results in inflammation of the vestibular nerve. Symptoms of vestibular neuritis come on suddenly and can cause unsteadiness, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms usually last a few hours or days but can take up to six weeks to resolve completely.

Vestibular neuronitis and labyrinthitis are often used interchangeably, but in neuronitis only the vestibular nerve is inflamed; in labyrinthitis the labyrinth is affected as well. Vestibular neuritis is a very common cause of vertigo, labyrinthitis is much rarer, and because the cochlea is invariably involved, there is always some degree of hearing loss in labyrinthitis.

Ménière’s disease is a rare inner ear disorder which can cause vertigo. Along with tinnitus and hearing loss, patients experience sudden attacks of vertigo which can last for around two to three hours. These symptoms may take a couple of days to completely disappear.4 It is thought that Ménière’s disease is caused by a raised volume of fluid in the labyrinth, which causes distension. This can cause damage to, and thus dysfunction of, the vestibular system and the cochlea.9

Central2:

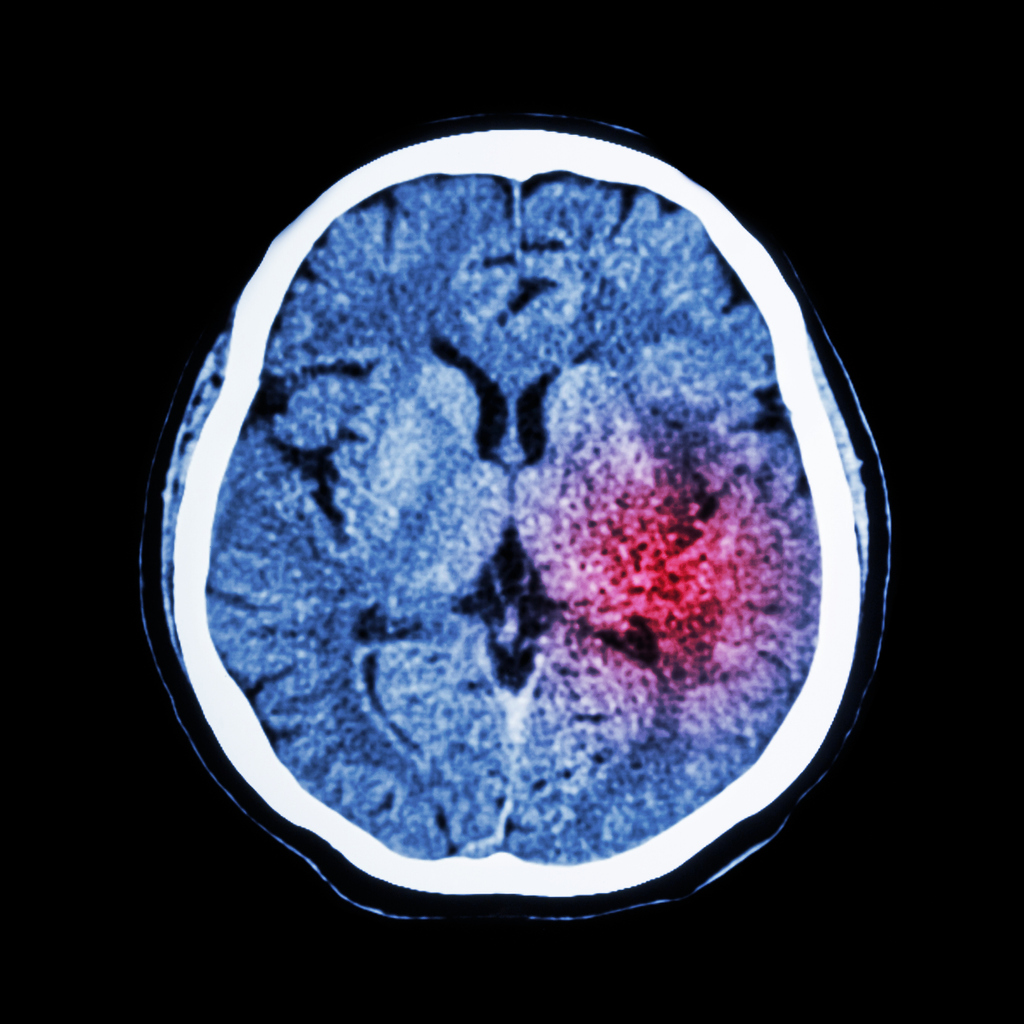

Central vertigo results from a disorder or dysfunction or the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, or brain stem.

Migraines are the most common cause of central vertigo. Vestibular migraines can cause ataxia, visual disturbances, occipital pain, nausea and vomiting.

Other less common causes of central vertigo include stroke and transient ischaemic attacks, brain tumours, multiple sclerosis and acoustic neuroma.

According to the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on Vertigo, the assessment of a person presenting with vertigo should consist of the following:

- description of the vertigo

- associated symptoms

- relevant medical history – including ear infections, migraine, head trauma and cardiovascular risks.

To distinguish between peripheral or central vertigo on examination, you can perform a rapid head impulse test. This test demonstrates the function of the peripheral vestibular system. If the test is abnormal, peripheral vertigo is suspected and if it is normal, central vertigo is suspected1,3.

The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre can also be used to determine a diagnosis of BBPV in patients with positional vertigo. This test reproduces the patient’s vertigo and possible nystagmus to determine which ear is abnormal and therefore causing the condition.

Treating central vertigo usually starts with treating the migraine, as this is the most common cause. This should usually relieve the vertigo symptoms5. If primary care treatments fail to treat these symptoms or a more serious pathology is suspected, referral to secondary care is recommended4. The urgency of the referral depends on the severity of the symptoms and what may be causing them2.

For peripheral vertigo, canalith repositioning procedures (CRPs) can be used to treat people with BPPV. It focuses on moving the dislodged otoconia back to their correct place in the ear6.

For peripheral vertigo, canalith repositioning procedures (CRPs) can be used to treat people with BPPV. It focuses on moving the dislodged otoconia back to their correct place in the ear6.

Epley manoeuvre: If the patient has positional vertigo and a positive Dix-Hallpike test, the Epley manoeuvre is indicated. It focuses on moving the otoconia back into the saccule. It can also be performed immediately after diagnostic tests and can be repeated if necessary to relieve symptoms. 74% of patients have total resolution of their symptoms within a week of the manoeuvre1. View a diagram and step by step.

Brandt-Daroff: This is recommended if CRPs are ineffective or not suitable. Brandt-Daroff is a treatment for BPPV that can be performed at home without supervision. The repetitive movements encourage the otoconia to move back to their correct position in the inner ear. Discover a step by step of the Brandt-Daroff exercises.

Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises: Management of the underlying cause of the vertigo is the first line treatment. However exercises such as Cawthorne-Cooksey are a form of vestibular rehabilitation which promote central compensation for vestibular dysfunction and offer treatment for chronic vertigo. Doing this may make the dizziness symptoms worse for a few days after the exercises, but perseverance may help to alleviate the symptoms over time6. View step by step instructions. BPPV and Ménière’s disease may not respond well to vestibular rehabilitation.

Medication is generally not recommended to treat vertigo. If a patient is waiting to be admitted to hospital or seen by a specialist, NICE recommend prescribing short-term symptomatic drug treatment to relieve symptoms of nausea and vomiting2. This is recommended for both central and peripheral vertigo if the patient is experiencing severe symptoms. To relieve severe symptoms rapidly, NICE suggest giving the patient buccal prochlorperazine, or a deep intramuscular injection of prochlorperazine or cyclizine. For less severe symptoms, short-term oral courses of vestibular sedatives, such as prochlorperazine, or cinnarizine, cyclizine, or promethazine teoclate (antihistamines) are recommended2. These vestibular sedatives help to suppress the receptors in the semi-circular canals of the inner ear and therefore reduce vestibular hyperactivity. These sedatives can ease the symptoms of dizziness and vomiting that vertigo can cause, but are not a long-term solution as they prolong the body’s readjustment after an instance of vertigo7.

References

1 Molnar A., et al. 2014. Diagnosing and Treating Dizziness. Medical Clinics, Volume 98, Issue 3, 583 – 596. Available at: https://www.medical.theclinics.com/article/S0025-7125(14)00029-7/fulltext

2 NICE. 2017. Clinical Knowledge Summary. Vertigo. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/vertigo

3 Northwestern University Emergency Medicine blog. 2018. Vertigo: A hint on the HiNTs exam. [Online] Available at: https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hints

4 NHS Inform. 2019. Meniere’s disease. [Online] Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/menieres-disease

5 NHS Inform. 2019. Vertigo. [Online]. Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/vertigo

6 Brain and Spine Foundation. 2017. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises. [Online] Available at: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/our-publications/our-fact-sheets/vestibular-rehabilitation-exercises/

7 ENT UK. 2017. Vertigo. [Online] Available at: https://www.entuk.org/vertigo

8 Payne, J. 2016. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo [Online] Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/benign-paroxysmal-positional-vertigo-pro

9 Henderson, R. 2015. Ménière’s Disease [Online] Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/menieres-disease-pro

May marks Action on Stroke Month, which is organised by the Stroke Association.

May marks Action on Stroke Month, which is organised by the Stroke Association.

In 2011, Public Health England launched the ‘FAST – Face-Arm-Speech-Time’ campaign to increase awareness of the signs of a stroke and fast access to treatment. Treating at 90 minutes will result in 10% more patients being independent at three months post-stroke than if treatment is given at three hours. Stroke is often thought of as an illness of old age but 10-15% of ischaemic strokes occur in young adults1. ‘Young adults’ are broadly defined as aged between 18-50 years of age2.

The worldwide incidence of ischaemic stroke in those aged 18-50 has increased up to 40% in recent decades, with around 2 million people suffering ischaemic stroke each year2. In England, approximately 57,000 people had a stroke for the first time in 2016, 3% of whom were aged under 403.

Strokes in younger adults have a more significant economic impact due to patients being left disabled during their most productive years1. The prevalence of vascular risk factors for stroke in younger adults can differ from those in older adults and may not be as routinely screened for. The primary stroke prevention strategy is to reduce potential risk factors such as:

Atrial fibrillation (AF)

There are around 1.4 million people with AF in the UK4. It is the most common cardiac arrhythmia contributing to significant morbidity and mortality5. A 2015 study found that around 10% of young stroke patients (≥50) had AF6. The risk of stroke increases five-fold for people with AF and it contributes to around one in five strokes. AF related strokes are often more severe and have higher mortality and disability rates7. However, a quarter of people with AF remain undiagnosed. Our RCGP eLearning course on AF contains more information on its management, anticoagulation and risk assessment.

Elevated Lipids

Hyperlipidaemia contributes to the development of atherosclerotic plaques, so statins are indicated for primary prevention when the 10 year risk of cardiovascular events is high. In secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke, a high intensity statin (such as atorvastatin 20-80mg daily) is used, with the aim of reducing non-HDL cholesterol by more than 40%8.

Hypertension

Hypertension affects around 9.5 million people in the UK and can triple the risk of stroke and heart disease9. Worldwide it is a contributing factor to approximately half of stroke episodes1. Lifestyle modifications, such as exercise, weight loss and reduced alcohol consumption, should be advised, but depending on an individual’s risk assessment, antihypertensives may be necessary.

Lifestyle

Factors such as obesity, smoking, drinking alcohol and using recreational drugs can increase the risk of stroke. Drugs such as cocaine can acutely and markedly increase blood pressure. This can then lead to both ischaemic or haemorrhagic strokes. It’s estimated that around 6 out of 10 young adults were regularly engaging in smoking, alcohol abuse or recreational drug use at the time of their stroke9.

GPs can play a key role in preventing a stroke in a young adult by detecting, treating and monitoring AF. The Stroke Association’s 'Detect, Protect and Perfect' AF toolkit details the ways that CCGs can implement policies to identify those with AF and reduce their stroke risk. The data in this document focuses on London CCGs but the methodologies and resources can be applied throughout the UK. View examples of other CCGs that have used ‘Detect Protect and Perfect’. The Stroke Association’s ‘AF: How can we do better?’ document, which was produced in partnership with the RCGP and other health organisations, looks at data in England but includes key messages that can be applied in all four countries. Regular reviews are vital for patients with AF, and any patient aged under 50 who has a stroke or TIA should be tested for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Patients with thromboembolic events and women who have recurrent miscarriages should also be considered for a test for APS.

GPs can play a key role in preventing a stroke in a young adult by detecting, treating and monitoring AF. The Stroke Association’s 'Detect, Protect and Perfect' AF toolkit details the ways that CCGs can implement policies to identify those with AF and reduce their stroke risk. The data in this document focuses on London CCGs but the methodologies and resources can be applied throughout the UK. View examples of other CCGs that have used ‘Detect Protect and Perfect’. The Stroke Association’s ‘AF: How can we do better?’ document, which was produced in partnership with the RCGP and other health organisations, looks at data in England but includes key messages that can be applied in all four countries. Regular reviews are vital for patients with AF, and any patient aged under 50 who has a stroke or TIA should be tested for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Patients with thromboembolic events and women who have recurrent miscarriages should also be considered for a test for APS.

For more information on stroke risks and contributing factors, you can access the following RCGP resources for free:

Atrial Fibrillation – 1 CPD point

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) – 0.5 CPD points

Alcohol: Identification and Brief Advice – 2 CPD points

Behaviour change and cancer prevention – 0.5 CPD points

Essentials of smoking cessation – 0.5 CPD points

Management of Obesity in General Practice – 5 minute screencast

RCGP members can also benefit from free access to the following resources:

EKU 4: Management of Patients with Stroke or TIA

EKU 15: Atrial fibrillation & New Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

References

1 Smajlović D. 2015. Strokes in young adults: epidemiology and prevention. Vascular health and risk management, 11, 157–164. DOI:10.2147/VHRM.S53203

2 Cited in: Ekker MS et al. 2018. Epidemiology, aetiology, and management of ischaemic stroke in young adults. The Lancet. Volume 17, issue 9, p790-801, 01 September 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30233-3

3 Public Health England. 2018. Briefing document: First incidence of stroke. Estimates for England 2007 to 2016. [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/678444/Stroke_incidence_briefing_document_2018.pdf

4 Stroke Association. 2018. AF: How can we do better? [Online] Available at: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/af-data_2018_england_eng_2.pdf

5 Aggarwal, N., Selvendran, S., Raphael, C. E., & Vassiliou, V. 2015. Atrial Fibrillation in the Young: A Neurologist's Nightmare. Neurology research international, 2015, 374352. doi:10.1155/2015/374352

6 Sanak D., Hutyra M., Kral M., et al. 2015. Atrial fibrillation in young ischemic stroke patients: an underestimated cause. European Neurology. 2015;73(3-4):158–163.

7 NICE. 2018. Atrial fibrillation. Scenario: First or new presentation of AF. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/atrial-fibrillation#!scenarioRecommendation:4

8 NICE. 2017. Clinical knowledge summary. Stroke and TIA. [Online] Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/stroke-and-tia#!scenario:2

9 Cited in: Stroke Association, 2018. State of the nation. [Online]

World Parkinson’s Day takes place every year on 11th April. Parkinson’s UK is using this year’s event to highlight the realities of living with Parkinson’s disease, helping patients to feel more understood1.

World Parkinson’s Day takes place every year on 11th April. Parkinson’s UK is using this year’s event to highlight the realities of living with Parkinson’s disease, helping patients to feel more understood1.

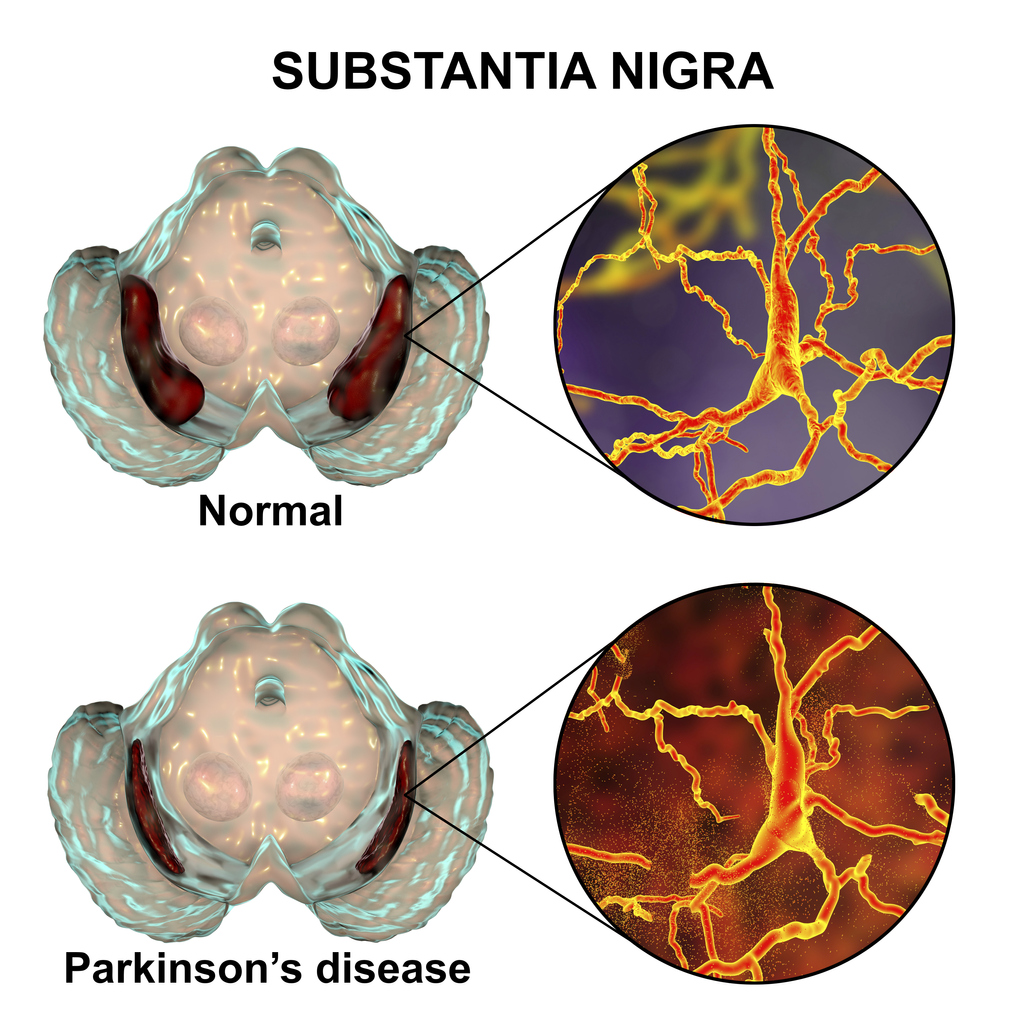

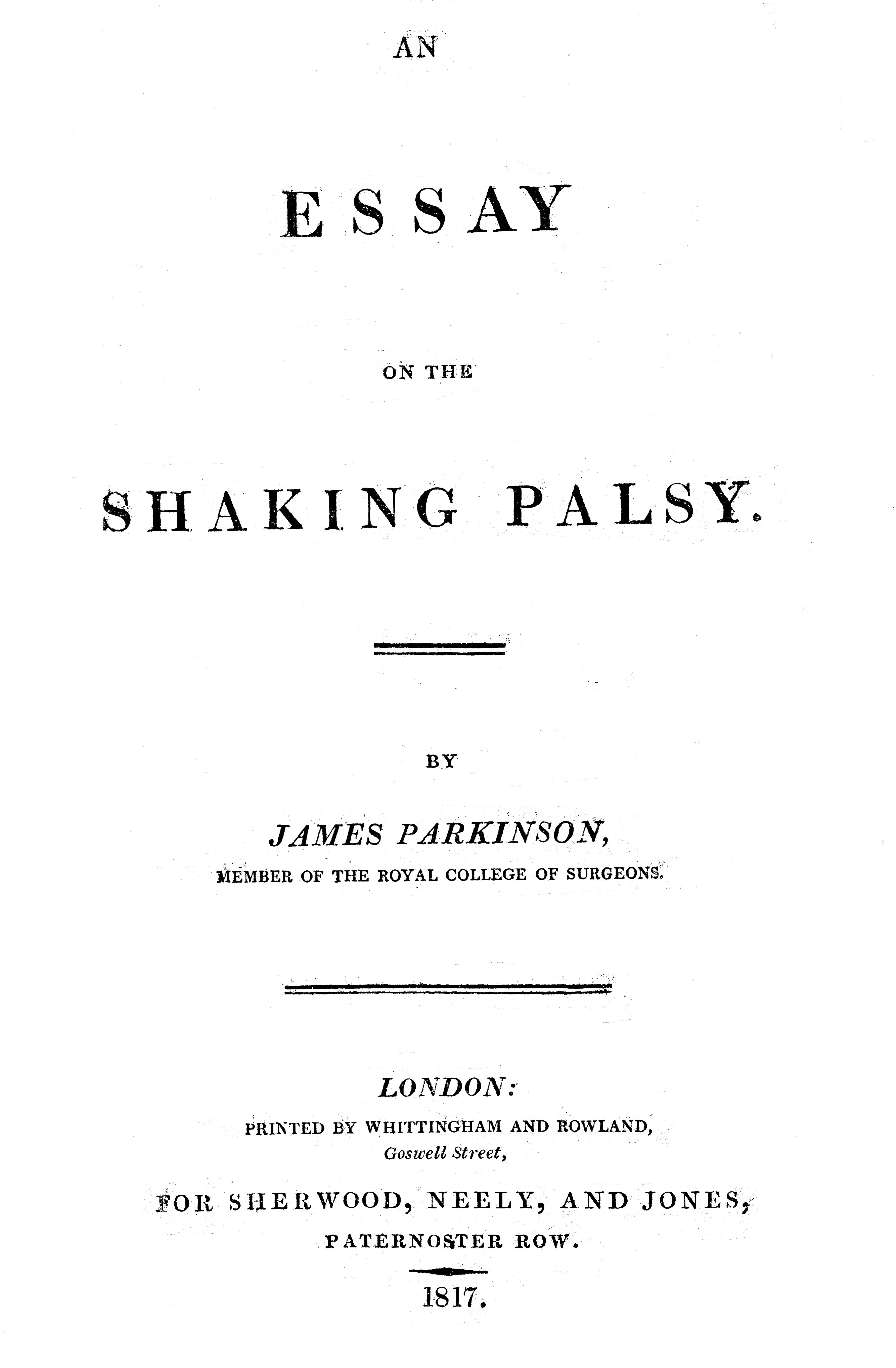

Parkinson’s disease was first described in ‘An essay on the shaking palsy’, written by Dr James Parkinson, an English physician and surgeon, in 18172. This paper established Parkinson’s disease as a recognised medical condition, which NICE defines as: “a progressive neurodegenerative condition resulting from the death of dopamine-containing cells of the substantia nigra in the brain”3. The substantia nigra pars compacta plays an important role in controlling the body’s movement and coordination, in conjunction with the caudate nucleus and putamen.

Parkinson’s is one of the most common neurological conditions and it’s estimated that it affects up to 16 people per 10,0003. According to a report by Parkinson’s UK, the estimated prevalence in the UK for 2018 was 145,519. The charity also found that prevalence was 1.5 times higher in men than in women within the 50-89 age group. In terms of incidence, Parkinson’s UK estimates that approximately 1 in 37 people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s at some point in their lifetime. They predict that the prevalence of the disease will rise by 18% between 2018 and 2025, due to population growth and an increasingly ageing population4.

Typical presentations of Parkinson’s disease include symptoms and signs described as ‘Parkinsonism’: bradykinesia (slow movements), rigidity (abnormal stiffness), resting tremor (typically ‘pill rolling’) and postural instability (loss of balance)1. These symptoms are typically asymmetrical2.

Rigidity can present in different forms including lead-pipe (sustained rigidity, where the limb is heavy and resistant to passive movements) and cogwheel (intermittent rigidity, where the limb moves with jerky and ratcheting motions)5. A ‘pill rolling’ tremor is often seen and is so named because it looks like the patient is rolling a pill between their thumb and index finger. It occurs at rest and can often be alleviated by moving the affected limb. A resting tremor can also occur in other parts of the body such as the legs and lips5. Postural instability is a major reason why people with Parkinson’s disease are at risk of falls: Parkinson’s affects the basal ganglia, which have an inhibitory action on movement. Releasing this inhibition requires the release of dopamine, so the deficiency results in hypokinesia. Freezing gait can also contribute to falls as it can cause patients to stop involuntarily when walking. They may then find themselves unable to initiate movement for several seconds/minutes5. In addition, basal ganglia control balance through cortico-spinal pathways, including auto-adjustment of posture to maintain stability, so reflexes which try to prevent falling are significantly impacted.

Examples of bradykinesia and rigidity include2:

- reduced arm swing

- shuffled gait

- softened voice

- decreased blink rate and facial expression.

Non-motor symptoms include2:

- fatigue

- autonomic dysfunction

- sleep disturbance.

It’s important to note that some conditions may look like Parkinson’s disease. For example, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy or extra-pyramidal side effects of drugs, such as antipsychotics or antiemetics can cause Parkinsonian features3.

Parkinson’s disease is usually diagnosed in secondary care, so any suspected cases should be referred to a neurologist to be seen within 6 weeks3. There are no laboratory or imaging tests that can offer a definitive diagnosis, so diagnosis is usually made based on a detailed clinical history and examination3,6. A specialist in secondary care may use the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank Criteria to assist with diagnosis6.

Parkinson’s disease is usually diagnosed in secondary care, so any suspected cases should be referred to a neurologist to be seen within 6 weeks3. There are no laboratory or imaging tests that can offer a definitive diagnosis, so diagnosis is usually made based on a detailed clinical history and examination3,6. A specialist in secondary care may use the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank Criteria to assist with diagnosis6.

The majority of management is in secondary care and it is recommended that patients receive a follow up every 6-12 months with a specialist who monitors treatment and progression of the condition. Patients with Parkinson’s disease are usually assigned to a Parkinson’s Disease Nurse Specialist (PDNS) who can co-ordinate care with the patient, carer, GP and specialist6. Patients should also be given access to occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech therapy - depending on the severity of their symptoms - to assist with their independence and safety6.

Medication is initiated in secondary care and can be prescribed by the GP after this, in accordance with the local shared care guidelines. Occasionally GPs may be involved with monitoring medication, in liaison with the PDNS6. The following medications are common pharmacological treatments for Parkinson’s disease:

Levodopa

This is a dopamine precursor that converts to endogenous dopamine in the brain. Itis offered to patients in the early stages of the disease, where motor symptoms are already having an impact on their quality of life3,6. Levodopa is considered the core medication in treating Parkinson’s, but it requires close monitoring to get the dosage right. If the dosage is too high, it can result in hallucinations and psychotic behaviour. As the disease progresses and higher doses are needed, adverse effects of levodopa, such as dyskinesias, are more common. Adjusting the dosage, timing and type of preparation can help to manage these effects6.

Dopamine agonists

Another treatment option is the use of drugs that have a dopamine-like action. These stimulate dopamine receptors in the brain and can be used on their own or with levodopa. Patients are likely to experience less long-term side effects from dopamine agonists, but they can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness and sickness if not introduced gradually. Older patients may experience hallucinations. A small percentage of Parkinson’s patients may experience impulsive and compulsive behaviour when taking dopamine agonists. These patients may also be more prone to ‘dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome’ when their treatment is stopped or reduced6.

Other key medications in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease include MAO-B inhibitors and COMT inhibitors. The NICE guidance on Parkinson’s disease in Adults (NG71) and the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on Parkinson’s disease provides more information on these, as well as more comprehensive lists of Parkinson’s medications and possible side effects.

Some medications may be contraindicated as they may cause worsening of the disease by antagonising dopamine receptors. As mentioned before, antipsychotics and anti-sickness drugs can cause extra-pyramidal side effects. These drugs can increase the severity of the Parkinsonian symptoms, particularly rigidity and bradykinesia, and sometimes irreversibly. A list of drugs to avoid can be found in the ‘drug treatments’ section of the Parkinson’s UK website.

GPs are a great source of support for patients with Parkinson’s disease, along with their family members and carers. Through support from their GP, patients are encouraged to take part in decision making and judgements about their own care. As Parkinson’s can affect a patient’s cognition and communication, NICE recommend that any information that is communicated throughout their disease should be given both verbally and in written form3. Family members and carers should also be kept informed about the patient’s condition, advised about their entitlements as a carer, encouraged to request a carer’s assessment from the local authority, and signposted to support services3. As mentioned earlier on, patients with Parkinson’s disease can be prone to falls due to their hypokinesia and balance impairment, so GPs will need to bear this mind when managing other medical conditions connected to falls, such as blood pressure. Orthostatic hypotension is common in Parkinson’s so extra care is needed when prescribing antihypertensives.

As a patient’s disease progresses, GPs are advised to be vigilant to any cognitive impairment. Parkinson’s is associated with Lewy body dementia and if this is suspected, referral to a consultant in older person’s mental health is recommended. As with any chronic disease, GPs should also look out for any signs of depression and screen for this intermittently. Signs of depression may be harder to detect due to the impaired facial expression and verbal difficulties that patients with Parkinson’s disease can experience.

To find out more about Parkinson’s disease and the GP’s role, RCGP members can benefit from access to the following online resources:

EKU6 - Diagnosis and Management of Parkinson's Disease

EKU12 - The Professional's Guide to Parkinson's Disease

References

1 Parkinson’s UK, 2019. Parkinson’s is. [Online] Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/get-involved/parkinsons-is

2 British Medical Journal, 2018. BMJ Best Practice – Parkinson’s disease. [Online] Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/147

3 NICE, 2017. Parkinson’s disease in adults (NG71). [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71

4 Parkinson’s UK, 2018. The incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s in the UK report. [Online] Available at:https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/incidence-and-prevalence-parkinsons-uk-report

5 Parkinson's Europe, 2017. Motor symptoms. [Online] Available at: https://parkinsonseurope.org/signs-and-symptoms/symptoms/

6 Guidelines, 2012. The GP’s guide to Parkinson’s – by Parkinson’s UK. [Online] Available at: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/neurology-/the-gps-guide-to-parkinsons/453864.article

'An essay on the shaking palsy by James Parkinson' image from Wellcome Collection.

World Bipolar Day takes place every year on 30th March and is organised by various international charity organisations, who support people with bipolar disorder. The aim of the awareness day is to inform people about bipolar disorder and to improve attitudes towards the condition by eliminating the social stigma around it1. Bipolar disorder (previously known as manic depression) is a lifelong mental health condition, consisting of recurring episodes of depression and mania or hypomania2. Whilst bipolar disorder is usually diagnosed in secondary care, patients are likely to present in primary care first. Therefore, it is important for GPs to be able to recognise the signs and symptoms in order to refer to secondary care for formal diagnosis.

World Bipolar Day takes place every year on 30th March and is organised by various international charity organisations, who support people with bipolar disorder. The aim of the awareness day is to inform people about bipolar disorder and to improve attitudes towards the condition by eliminating the social stigma around it1. Bipolar disorder (previously known as manic depression) is a lifelong mental health condition, consisting of recurring episodes of depression and mania or hypomania2. Whilst bipolar disorder is usually diagnosed in secondary care, patients are likely to present in primary care first. Therefore, it is important for GPs to be able to recognise the signs and symptoms in order to refer to secondary care for formal diagnosis.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimate that the peak age of onset is 15-19 years old. As bipolar disorder can often be difficult to detect initially, there is usually a significant delay between onset and first contact with mental health services3,4.

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, conducted in 2014, found that 2% of the English population screened positive for bipolar spectrum disorders2.

The elevated mood in bipolar may be hypomania or mania, the definitions of which are as follows6:

Mania – Abnormally and persistently elevated or irritable mood for a distinct period of at least one week (with or without psychotic symptoms).

Hypomania – Mild mood elevation with increased energy and irritability, that lasts for 4 or more continuous days.

Depressive symptoms are the most common initial presentation in primary care, which makes it difficult to recognise them as being part of bipolar disorder. Patients may present with symptoms such as depression, anxiety, mood swings, sleep disturbance, irritability, fatigue and difficulty in focus and concentration4. To make a distinction between depression and bipolar disorder, ask the patient about periods of elated, excited or irritable mood lasting four days or more. It is also recommended that GPs take a family history of mania and depression7.

Depressive symptoms are the most common initial presentation in primary care, which makes it difficult to recognise them as being part of bipolar disorder. Patients may present with symptoms such as depression, anxiety, mood swings, sleep disturbance, irritability, fatigue and difficulty in focus and concentration4. To make a distinction between depression and bipolar disorder, ask the patient about periods of elated, excited or irritable mood lasting four days or more. It is also recommended that GPs take a family history of mania and depression7.

Patients who have been diagnosed and treated in secondary care should return to primary care with a mutually agreed care plan in place. This includes their recovery goals, a crisis plan which indicates early warning symptoms of a relapse and what do in this instance, an assessment of their mental state, and a medication plan with a date for review3. Both the patient and their GP should have a copy of this plan so that the GP can begin monitoring their condition in primary care.

Following diagnosis and stabilisation, the primary care team’s role is to optimise physical health, check mental state and review the patient’s medication (as would happen in any chronic disease management). Unwell patients will need help from their mental health teams if destabilisation occurs which cannot be managed in primary care.

Medication

From the care plan provided, the GP should have all the details concerning the patient’s medication and when it should be reviewed. However, NICE states that the secondary care team should be responsible for monitoring the efficacy of the patient’s antipsychotic medication for at least the first 12 months, or until the patient’s condition has stabilised, whichever is longer3. Following this, the responsibility for this monitoring may transfer to primary care under shared-care agreements.

If the patient is on lithium, the psychiatry team should provide a target lithium level (typically 0.6-0.8 mmol/L, depending on the patient). It is recommended that GPs check the levels every three months and monitor and adjust accordingly7, but if the patient becomes unstable they should be referred back to secondary care, in line with local shared care guidelines. The NICE guideline on ‘Bipolar disorder: assessment and management’ includes more specific information about the different pharmacological options for bipolar disorder and their use.

Physical health checks

As well as monitoring medication, it is recommended that GPs perform a physical health check on patients with bipolar disorder at least annually. According to NICE, these checks should include3:

- Weight, BMI, diet and nutrition and levels of exercise

- Pulse and blood pressure

- Fasting blood glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and blood lipid profile

- Liver function

- Renal and thyroid function

- Calcium levels (for people taking long-term lithium)

It is estimated that the life expectancy for people living with severe mental illness is 15-20 years lower than the general population8. This statistic highlights the importance of carrying out the checks above and managing any potential comorbidities alongside treatment for bipolar disorder.

Support

As part of their regular reviews, GPs should provide holistic support to bipolar disorder patients and their families/carers. This includes preparing for major life events: for example, all patients planning a pregnancy or who have become pregnant should be immediately referred to the perinatal mental health service to advise the patient on the management of their medication in relation to their pregnancy. A good social history during visits will reveal important life changes that might be detrimental to the patient’s health such as changes in social or family situations or their general wellbeing4. As well as building relationships with the patient and their families/carers, the GP can help carrying out the care plans from secondary care and help with recovery goals.

For more information about the diagnosis and management of bipolar disorder, RCGP members can access the following eLearning resources for free:

EKU15: Assessment & Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults, Children & Young People

EKU13 (Briefing): Bipolar Disorder – Diagnosis & Current Treatment Options

References

1 World Bipolar Day, 2019. About World Bipolar Day. [Online] Available at: http://www.worldbipolarday.org/about-wbd.html

2 Marwaha S, Sal N, Bebbington P, 2016. ‘Chapter 9: Bipolar disorder’ in McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T. (eds) Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital. Available at:

3 NICE, 2014. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management (CG185). [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/resources/bipolar-disorder-assessment-and-management-pdf-35109814379461

4 Culpepper L, 2010. ‘The role of primary care clinicians in diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder’. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry vol. 12, Suppl 1 (2010): 4-9. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2902189/

5 Merikangas, Kathleen R et al. “Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative” Archives of general psychiatry vol. 68,3 (2011): 241-51. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3486639/

6 Mind, 2018. What types of bipolar are there? [Online]. Available at: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/bipolar-disorder/types-of-bipolar/#.XFgoXFz7S70

7 Goodwin GM et al, 2016. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendation from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Pharmacology 2016, Vol 30(6) 495-553. Available at: https://www.bap.org.uk/pdfs/BAP_Guidelines-Bipolar.pdf

8 NHS England, 2018. Improving physical healthcare for people living with severe mental illness (SMI) in primary care: Guidance for CCGs. [Online] Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/improving-physical-healthcare-for-people-living-with-severe-mental-illness-smi-in-primary-care-guidance-for-ccgs/

This February is “Raynaud’s Awareness Month”. This common dermatological phenomenon was named after Maurice Raynaud, who in 1862 described the condition afflicting a 26 year old female patient. Although epidemiology varies depending on local weather, work exposure and sex, most population-based surveys estimate its prevalence between 3 to 5%. Patients can be divided into two different groups: those with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is diagnosed when no underlying disease is found; and those with secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is diagnosed when there is an associated disease. The differentiation between the two of them is of importance, as secondary Raynaud’s has the potential for serious complications. Its associated diagnoses -systemic sclerosis, vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral vascular disease - are potentially serious and can cause deterioration in quality of life. As 30 to 50% of patients with primary Raynaud’s have a first degree relative condition, a genetic component is likely1.

This February is “Raynaud’s Awareness Month”. This common dermatological phenomenon was named after Maurice Raynaud, who in 1862 described the condition afflicting a 26 year old female patient. Although epidemiology varies depending on local weather, work exposure and sex, most population-based surveys estimate its prevalence between 3 to 5%. Patients can be divided into two different groups: those with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is diagnosed when no underlying disease is found; and those with secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is diagnosed when there is an associated disease. The differentiation between the two of them is of importance, as secondary Raynaud’s has the potential for serious complications. Its associated diagnoses -systemic sclerosis, vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral vascular disease - are potentially serious and can cause deterioration in quality of life. As 30 to 50% of patients with primary Raynaud’s have a first degree relative condition, a genetic component is likely1.

Patients describe well demarcated, episodic blanching of one or more fingers (or toes, ears, nipples and ears) caused by peripheral vasospasm and triggered by a cold environment or emotional stress. This can be followed by a blueish, cyanotic colour (in a third of all patients), before the fingers turn bright red during a period of reperfusion, associated with stinging and throbbing. The symptoms can last for minutes and up to several hours.

Raynaud’s phenomenon isn’t the only diagnosis that can cause vascular symptoms in the periphery: exposure to the cold can cause physiological pallor, an acute cholesterol embolism can mimic the discolouration of Raynaud’s phenomenon (though doesn’t have its episodic nature) and thrombangitis obliterans (recurrent thrombosis of small/medium arteries and veins) can cause similar distal extremity ischaemia2.

Raynaud’s phenomenon isn’t the only diagnosis that can cause vascular symptoms in the periphery: exposure to the cold can cause physiological pallor, an acute cholesterol embolism can mimic the discolouration of Raynaud’s phenomenon (though doesn’t have its episodic nature) and thrombangitis obliterans (recurrent thrombosis of small/medium arteries and veins) can cause similar distal extremity ischaemia2.

Patients who present with primary Raynaud’s are usually younger (between 15 and 30 years of age), don’t appear to have symptoms affecting their thumbs and lack ulceration, digital pitting or gangrene. Patients presenting in general practice should be asked about the frequency and severity of the attacks, smoking and family history and for symptoms associated with the diagnoses underlying secondary Raynaud’s.

Examination should involve checks for peripheral vascular disease, blood pressure measurements and evidence of complications of secondary Raynaud’s. Examination of the capillaries of the nailbeds of the fingers can be attempted with an otoscope, ophthalmoscope or a dermatoscope, as dilated and distorted capillaries can point to underlying connective tissue disease3. Investigations should include FBC, ESR, ANA, U&Es, and urinalysis.

If examination and investigation points to primary Raynaud’s, pharmacological treatments are often not necessary, and lifestyle advice should be considered first: keeping warm, smoking cessation, avoiding exposure to cold weather. If non-pharmacological treatments in primary Raynaud’s are ineffective, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine and nicardipine can be effective in reducing the frequency of attacks.

If treatment is ineffective or if there is suspicion of connective tissue disease or another underlying condition, the patient should be referred to the local rheumatology team4.

Images used with permission from the charity ‘Scleroderma & Raynaud’s UK’. Their website has extensive guidance for patients with Raynaud’s.

1 Fredrick M. Wigley and Nicholas A. Flavahan: Raynaud’s Phenomenon. August 11, 2016. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:556-565

2 Drerup, C; Ehrchen, J:Raynaud’s phenomenon. Practical management for dermatologists. Hautarzt 2019 · 70:131–141

3 Herrick, AL: Evidence-based management of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Ther Adv Musculoskel Dis, 2017, Vol. 9(12) 317–329

4 Pope, J: Raynaud’s phenomenon. BMJ Best practice. 2019. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/193

Young Carers Awareness Day takes place on 31st January 2019 and, according to the Carers Trust, the aim is to “identify young carers and raise awareness of the vital role that they play in supporting their sick and disabled family members”1. The number of young carers in England is difficult to determine; the latest census in 2011 found that there were around 175,0002, but a more recent survey by BBC News and Nottingham University estimates around 800,000 in secondary school alone3. One of the main reasons for this uncertainty is that young carers and their families are often reluctant to make themselves known to authorities for various reasons. This can make it extremely difficult for GPs to identify young carers in primary care and therefore support them effectively.

Young Carers Awareness Day takes place on 31st January 2019 and, according to the Carers Trust, the aim is to “identify young carers and raise awareness of the vital role that they play in supporting their sick and disabled family members”1. The number of young carers in England is difficult to determine; the latest census in 2011 found that there were around 175,0002, but a more recent survey by BBC News and Nottingham University estimates around 800,000 in secondary school alone3. One of the main reasons for this uncertainty is that young carers and their families are often reluctant to make themselves known to authorities for various reasons. This can make it extremely difficult for GPs to identify young carers in primary care and therefore support them effectively.

The theme of this year’s Young Carers Awareness Day is the importance of mental health, which can be significantly impacted when a child or young person is expected to juggle caring alongside their education and social life. Carers Trust estimates that around 45% of young adult carers have mental health problems4. The pressure of caring for one or multiple family members can cause a great deal of anxiety for both children and young adults, who are often the primary source of emotional support for the person/people they care for. The Dearden and Becker ‘Young Carers in the UK’ survey found that 82% of young carers provide emotional support as well as nursing-type care, intimate care and child care5.

It is not only a young carer’s mental health that is impacted by their caring role. Their physical health is often impaired due to lack of sleep, poor diet and having to lift a heavy adult6. These issues, combined with their responsibilities at home, can have a significant impact on their education and school life. It is estimated that young carers miss or cut short around 48 school days a year on average and only half have a person at school that knows about their caring role4. Barnardo’s, the children’s charity, highlight that young carers are often bullieddue to being ‘different’ from their peers and therefore feel isolated7. There are also limited opportunities for social activities and to build relationships outside of the family home. Around three quarters of young carers find the school holidays particularly difficult, due to feeling socially isolated and to the increase in their responsibilities at home4.

Whilst young carers face many difficulties, it is common for them to feel a sense of pride and independence due to their caring role. They also may not be fully aware that their life is different to their peers, which is one of the reasons why many young carers still remain ‘hidden’ from social services. Some families don’t recognise their children as ‘carers’, especially if the child helps their parents care for a sibling, so it is often not declared to local authorities. In other cases, the family is aware of their child’s caring role but worry about the repercussions of involving social services, such as interventions and the possibility of family separation8.

Whilst young carers face many difficulties, it is common for them to feel a sense of pride and independence due to their caring role. They also may not be fully aware that their life is different to their peers, which is one of the reasons why many young carers still remain ‘hidden’ from social services. Some families don’t recognise their children as ‘carers’, especially if the child helps their parents care for a sibling, so it is often not declared to local authorities. In other cases, the family is aware of their child’s caring role but worry about the repercussions of involving social services, such as interventions and the possibility of family separation8.

Without the involvement of social services, it is unlikely that a young carer would be known to their practice or GP. It is therefore important for GPs and practice teams to identify any young carers at the practice, so that they are aware of this during consultations and can signpost them to helpful resources. Young carers may also need to be involved in the care for the person they look after, such as appointments and medications. Some ways in which young carers can be identified include9:

- Putting posters and leaflets around in the waiting room, asking them to self-identify

- Adding a question in the new patient questionnaire at registration

- Looking out for any children or young people that bring an elderly, sick, disabled or frail patient in for an appointment and asking if they are the patient’s carer

- Ask any patients with chronic conditions that require a carer about who their carer is

For more information about identifying and supporting young carers, the RCGP has the following resources available to all healthcare professionals for free:

Supporting Carers in General Practice eLearning course – 3 CPD points

Taking Action to Support Carers in Practice Teams eLearning course - 2 CPD points

RCGP Members can also access the following resources about carers:

EKU2017.1: Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care

EKU9 Briefing: Assessing and helping carers of older people

EKU4: Supporting Carers. An action guide for general practitioners and their teams

GPs can also use the following resources to signpost patients and their families to:

References

1 Carers Trust. 2018. Young Carers Awareness Day 2019

https://carers.org/young-carers-awareness-day-2019

2 Office for National Statistics. 2011. 2011 Census

https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census

3 BBC. 2018. Being a young carer

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/Being_a_young_carer

4 Carers Trust. 2015. Key facts about carers and the people they care for

https://carers.org/key-facts-about-carers-and-people-they-care

5 Dearden, C. and Becker, S., 2004. Young carers in the UK: the 2004 report. London: Carers UK. Available from: https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/627

6 Carers Trust Professionals. 2014. Who are young carers?

https://professionals.carers.org/who-are-young-carers

7 Barnado’s. 2018. Young carers. http://www.barnardos.org.uk/what_we_do/our_work/young_carers.htm

8 Department for Education. 2016. The lives of young carers in England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/498115/DFE-RR499_The_lives_of_young_carers_in_England.pdf

9 Royal College of General Practitioners. 2013. Supporting Carers in General Practicehttps://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/view.php?id=139