Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

An ectopic pregnancy is one in which the fertilised egg implants outside of the uterus; around 95% are in a fallopian tube, but an ectopic can also occur on the ovary, elsewhere in the pelvis, and sometimes in the cervix or in a caesarean section scar. Around 1% of all pregnancies are ectopic, with this figure at least doubling for pregnancies arising from in-vitro fertilisation (IVF)1,2. Non-tubal ectopic pregnancies are associated with higher morbidity and mortality than tubal ectopics, often presenting late with a sudden onset of symptoms prior to rupture, collapse and death.

Bleeding from an ectopic pregnancy can be fatal and the numbers of deaths in the UK and Ireland increased between the 2018-20 and 2020-22 reporting periods (8 deaths in 2018-20 and 12 in 2022-22)3,4, with the 2024 MBRRACE-UK report noting that there were learning points for both primary and secondary care and that improvements to care may have made a difference for nine out of the 12 women who died. None were judged to have received good care, with three cases where improvements would probably not have affected the outcome. Many of these were around the presentation of women who did not know that they were pregnant; the rest of this blog will focus on the lessons for general practice. Those wanting more information on lessons for secondary care or the ambulance service can find them in the 2024 MBRRACE-UK report4.

Always consider the possibility of pregnancy

Unless there is a clear history of a total hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy, always consider pregnancy in a woman of reproductive age. Women who have irregular periods, or who have bled at the time of implantation, may not realise that they have missed a period; those who are pregnant as a result of failed contraception might not consider it as a possibility. Pregnancies due to a failure of sterilisation or intrauterine contraception in particular are at higher risk for being ectopic.

Symptoms may be atypical

When presented with a woman who has pelvic pain and/or vaginal bleeding, with a delayed period, most of us would consider an ectopic pregnancy. This may not be the case if the presentation is more subtle. Symptoms can include breast tenderness, diarrhoea or vomiting, dizziness, shoulder tip pain and rectal pressure, and some women will collapse with no previous symptoms and no knowledge that they are pregnant1,4. NICE gives the following advice: “During clinical assessment of women of reproductive age, be aware that they may be pregnant, and think about offering a pregnancy test even when symptoms are non-specific”5. If a home pregnancy test was done, consider whether it may have been done too early, such that a false negative result was obtained.

Do you know where pregnancy tests are kept at work?

General practice is not resourced to offer routine testing for confirmation of pregnancy, and this has in some cases led to tests being unavailable or locked away. It is important that all practices hold some easily accessible pregnancy tests so that they can be used when there is a clinical reason to do so. Women may not have done a test at home because they didn’t think pregnancy was a possibility, or because of issues with access or affordability; adolescents in particular are less likely to confirm pregnancy promptly with a test6.

There are issues with access to early pregnancy assessment units (EPAUs)

The MBRRACE-UK report4 described calls not returned, issues with language barriers, and waits of over 24 hours for an appointment. Clearly any woman who is haemodynamically unstable at presentation should be referred via the emergency department, rather than via EPAU, but a woman who is stable when seen by her GP, may not remain so over the course of a long wait for an EPAU appointment. Commissioning GPs reading this blog might want to reflect on EPAU access in their area; are women reliably seen within 24 hours, seven days a week, and does the service have access to enough people to answer the phone, and interpretation available in person and on the phone? As GPs, we should not be reticent in saying if we feel that a service for an individual patient isn’t good enough, and if an EPAU appointment isn’t offered in a reasonable timeframe then referral to the on-call gynaecology team may be appropriate.

Health inequalities matter

Vulnerable women are over-represented among those who died from an ectopic in 2020-2022, with one-sixth having language difficulties and nearly half having either a mental health diagnosis or issues with substance use or domestic abuse. These inequalities may prevent women’s concerns from being heard; practices should consider how the care of women who may find it more difficult to get their message across can be optimised, even in the difficult, time-pressured situation of the current NHS. The RCGP’s Health Inequalities Hub has more resources in this area.

How do you manage a pregnant woman with a past ectopic, or who is at a high risk for ectopic pregnancy?

Almost one in five women who has had an ectopic pregnancy will have another one1; this is largely unaffected by the mode of treatment for the original ectopic. Aftercare of a woman who has had an ectopic should include the fact that she needs a scan at around 6-7 weeks of gestation in any subsequent pregnancies, to ensure that the pregnancy is intrauterine1. Depending on local pathways, this may need to be arranged by the GP, or the woman may be given open access to EPAU to arrange this. An early scan should also be arranged if there is a history of damage to the fallopian tubes (including in pregnancy after failed or reversed sterilisation7), and in women who become pregnant with an intrauterine device in place; up to 50% of such pregnancies may be ectopic.

Further information

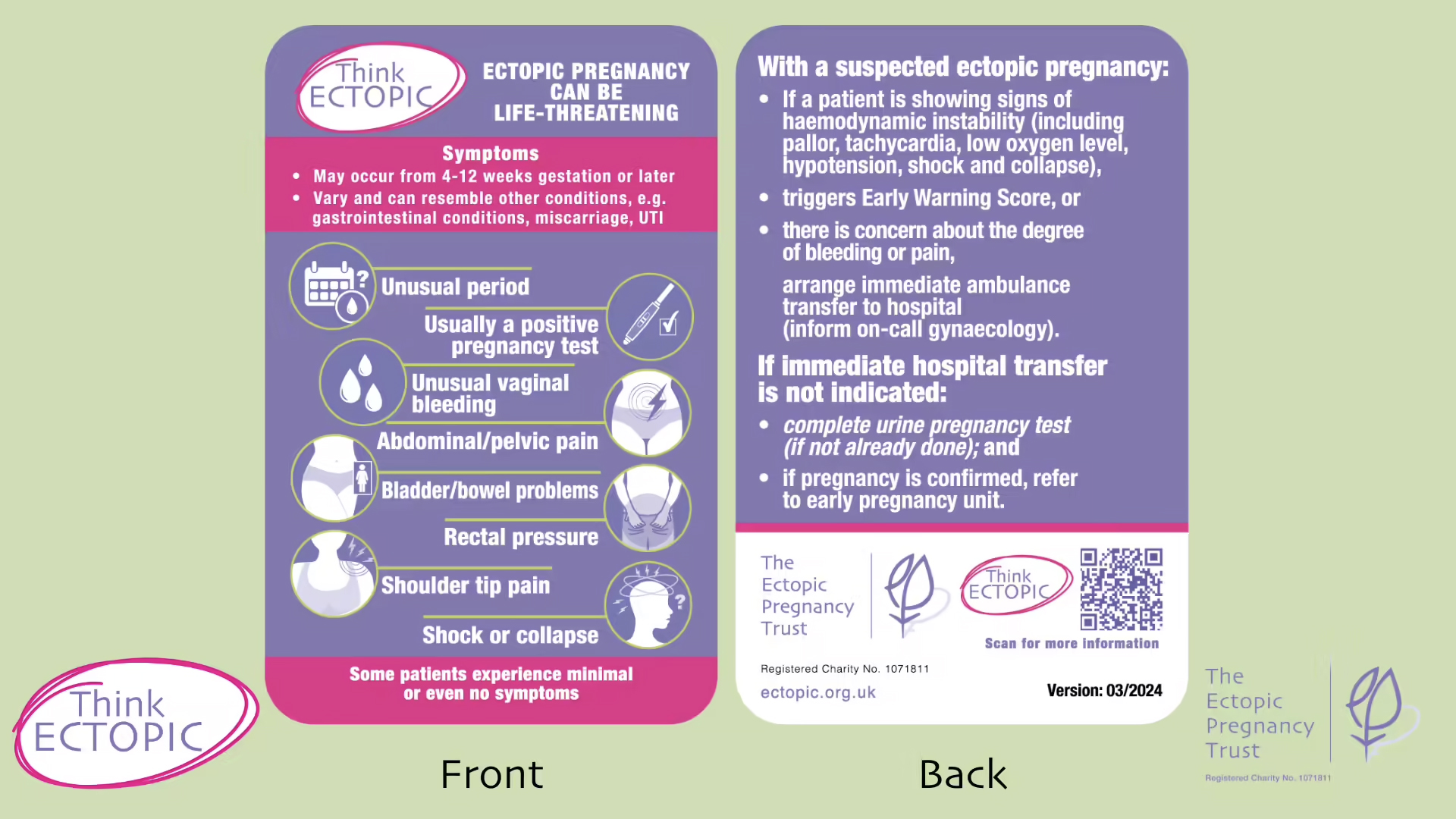

The MBRRACE-UK report emphasises the need to Think Ectopic, which aligns with a national campaign led by The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust, endorsed by the RCGP. At the heart of the campaign is an ectopic pregnancy biocard which reminds healthcare professionals about the signs of ectopic pregnancy and time critical next steps.

Figure: Think Ectopic Bio Card. The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust. Reproduced with permission.

Request free copies of the card from The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust.

References

- NICE CKS. Ectopic pregnancy. Feb 2023.

- Anzhel S, Mäkinen S, Tinkanen H et al. Top-quality embryo transfer is associated with lower odds of ectopic pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022 Jul; 101(7): 779-786.

- MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care. Nov 2022.

- MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care. Oct 2024.

- NICE. NG126. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. Aug 2023.

- Ralph LJ, Foster DG, Barar R, et al. Home pregnancy test use and timing of pregnancy confirmation among people seeking health care. Contraception. 2022 Mar; 107: 10-16.

- University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust. Laparoscopic sterilisation. Dec 2022.

- FSRH. Intrauterine contraception. July 2023.

July 2022 will see Integrated Care Systems (ICS) become statutory in England. Partnerships between NHS service providers, commissioners, local authorities, and other organisations will be responsible for planning, co-ordinating and commissioning health and care services that meet the needs of each geographically defined community. Included within each community will be a relatively small number of people who are in contact with the criminal justice system, some of whom will go in and out of prison more than once. It is recognised that this cohort, while heterogeneous, often has highly complex needs and frequently experiences poorer than average health access, experience, and outcomes.

July 2022 will see Integrated Care Systems (ICS) become statutory in England. Partnerships between NHS service providers, commissioners, local authorities, and other organisations will be responsible for planning, co-ordinating and commissioning health and care services that meet the needs of each geographically defined community. Included within each community will be a relatively small number of people who are in contact with the criminal justice system, some of whom will go in and out of prison more than once. It is recognised that this cohort, while heterogeneous, often has highly complex needs and frequently experiences poorer than average health access, experience, and outcomes.

Whilst in prison, men and women from this cohort will be temporarily ‘hidden’ from their community ICS commissioning landscape (commissioning of prison healthcare takes place separately, by NHS England and NHS Improvement health justice commissioners in England, Health Boards in Wales and Scotland and the South East Trust in Northern Ireland), and may be in secure settings distant from the locality to which they will return. It is essential that, as integrated care systems are launched, there will be representation and acknowledgement of the needs of these patients to avoid compounding the health inequalities gap. NHS England and NHS Improvement have introduced Core20PLUS5, an approach to address health inequalities at national and system levels. It identifies the most deprived 20% of the population, plus those not captured in the 20% who experience poorer than average health and recognises five ‘focus’ clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement. Those in touch with the criminal justice system are considered an ‘inclusion’ group in the PLUS cohort. This strategy aims to ensure that health and care needs are met in people in contact with the criminal justice system.

Once in prison, people are not able to choose where or from whom they receive their healthcare provision. Healthcare services in secure environments need to be configured to take account of the particular needs of the population they are serving, for example with regard to the increased prevalence of mental ill health, substance misuse and communicable diseases, whilst also acknowledging the distinctive settings in which the care needs to be delivered.

Healthcare practitioners have a duty of care to their patients, and in the secure setting this duty must be delivered in the context of the physical environment and lifestyle constraints prison brings, whilst utilising the assistance of the staff providing the security for the establishment. As a result, healthcare delivery in the secure setting requires continual collaboration and partnership working between prison and healthcare staff to deliver the most beneficial services.

A healthcare worker in a prison has a unique opportunity to address the needs of some of society’s most vulnerable people and this must be done without prejudice. This means that the nature of someone’s offence, or the reason for their detention, should not alter how patients are cared for.

Particular risks to patient safety, engagement and health equity occur at transition points, as people move into and out of prison, or are moved from one prison to another. NHS RECONNECT schemes have been set up to bridge the gap for patients being released from prison. They aim to facilitate continuity of care by ensuring that health information is shared, and connections are built with community health care practitioners before a patient leaves prison. The success of pre-release healthcare arrangements requires careful coordination with the probation service and the local authority to ensure that suitable housing is identified within the locality that community healthcare provision has been arranged.

In 1996, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons, Sir David Ramsbotham, published his paper “Patient or Prisoner?” in which his terms of reference were: ‘to consider health care arrangements in Prison Service establishments in England and Wales with a view to ensuring that prisoners are given access to the same quality and range of health care services as the general public receives from the National Health Service’. This paper introduced the concept of ‘equivalence’ of care and set the scene for what continues to be an evolving area of prison and secure environment medicine.

The principle of equivalence has been instrumental in helping to define and contrast the care being delivered in secure settings with that of the care in the wider community, with the aim of mirroring of provision. Since 2006 and the move towards the commissioning of health services in prisons by the National Health Service, there has been a significant transformation in the quality and consistency of services being delivered to people in prison. By aiming to deliver healthcare services that are ‘equivalent’, and achieving equitable health outcomes, we are not only striving to improve the health of our secure and detained patients, we are also benefitting society as a whole.

The RCGP has recently launched Secure Environments Hub that features information about healthcare in secure environments and eLearning for clinicians and multi-disciplinary team related to the prison system. You can access the Hub here: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/view.php?id=561