_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

“Medicine is an art whose magic and creative ability have long been recognised as residing in the interpersonal aspects of the patient-physician relationship1”.

Art is part of medical training from early on - lectures in medical school use images, cartoons, animations, and demonstration models. In our hospital jobs we all used drawings, lung fields with crosses, or a hexagon abdomen with a large liver on it were all used in the days of paper notes. However when asked to draw, medical students often recoil and claim that they are ‘not creative’ and cannot draw2.

We are trained in communication skills to gather information in order to facilitate accurate diagnosis, counsel and give therapeutic instructions whilst establishing caring relationships with patients3. Patients gather information from many different visual sources in the GP surgery, so using drawings is a natural next step, yet one that is rarely discussed.

We already use visual imagery in the consultation - as GPs we might point to anatomical posters in our rooms, use drawings for minor surgery consent, or the “clock test” in dementia screening. Encouraging people to see drawing as a form of learning can help them to present information more efficiently within the consultation4.

We also all use metaphor and analogy frequently - as Anatole Broyard describes, metaphors may be as necessary to illness as they are to literature and are a relief from medical terminology5. Metaphors bridge the communication gap between healthcare professionals and patients, examples including the following:

“My tongue feels weird, like licking a battery.” (Oral thrush)

“Doctor, you know when you put your hand in a bag of rice – that nice sort of tingly feeling – I get that in my head in a sort of shock.” (SSRI discontinuation syndrome)

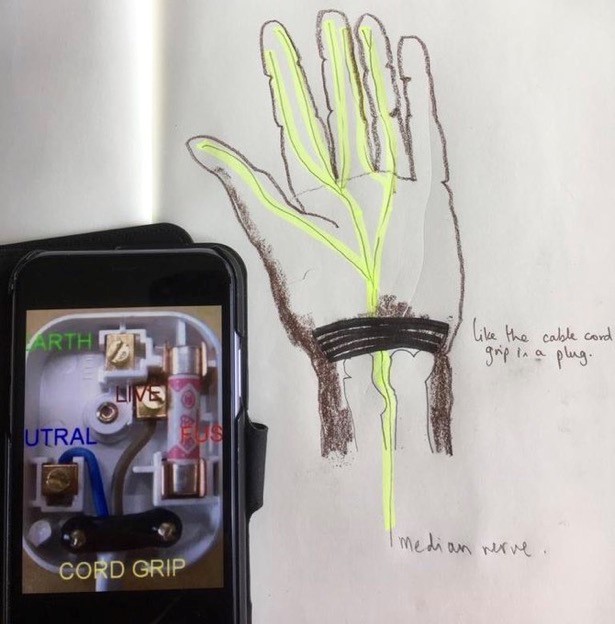

Clinicians can use visual metaphors; drawing a plug to describe the wrist retinaculum (Image 1) can increase understanding of the pathophysiology of carpal tunnel symptoms and be a simple start from which patients can improve their understanding.

Clinicians can use visual metaphors; drawing a plug to describe the wrist retinaculum (Image 1) can increase understanding of the pathophysiology of carpal tunnel symptoms and be a simple start from which patients can improve their understanding.

While anecdotal evidence for the benefits of drawing in the consultation is plentiful, research is limited: A team at Edinburgh university were the first to document the use of drawing amongst 100 surgeons, 92% of whom valued drawing in surgical practice2. Similarly, the vast majority of patients valued drawing in moderate or complex surgery consent explanations3. There is plenty of evidence for the neurological and cognitive benefits of using images in undergraduate and postgraduate pedagogy4, alongside the cognitive processing of learning5.

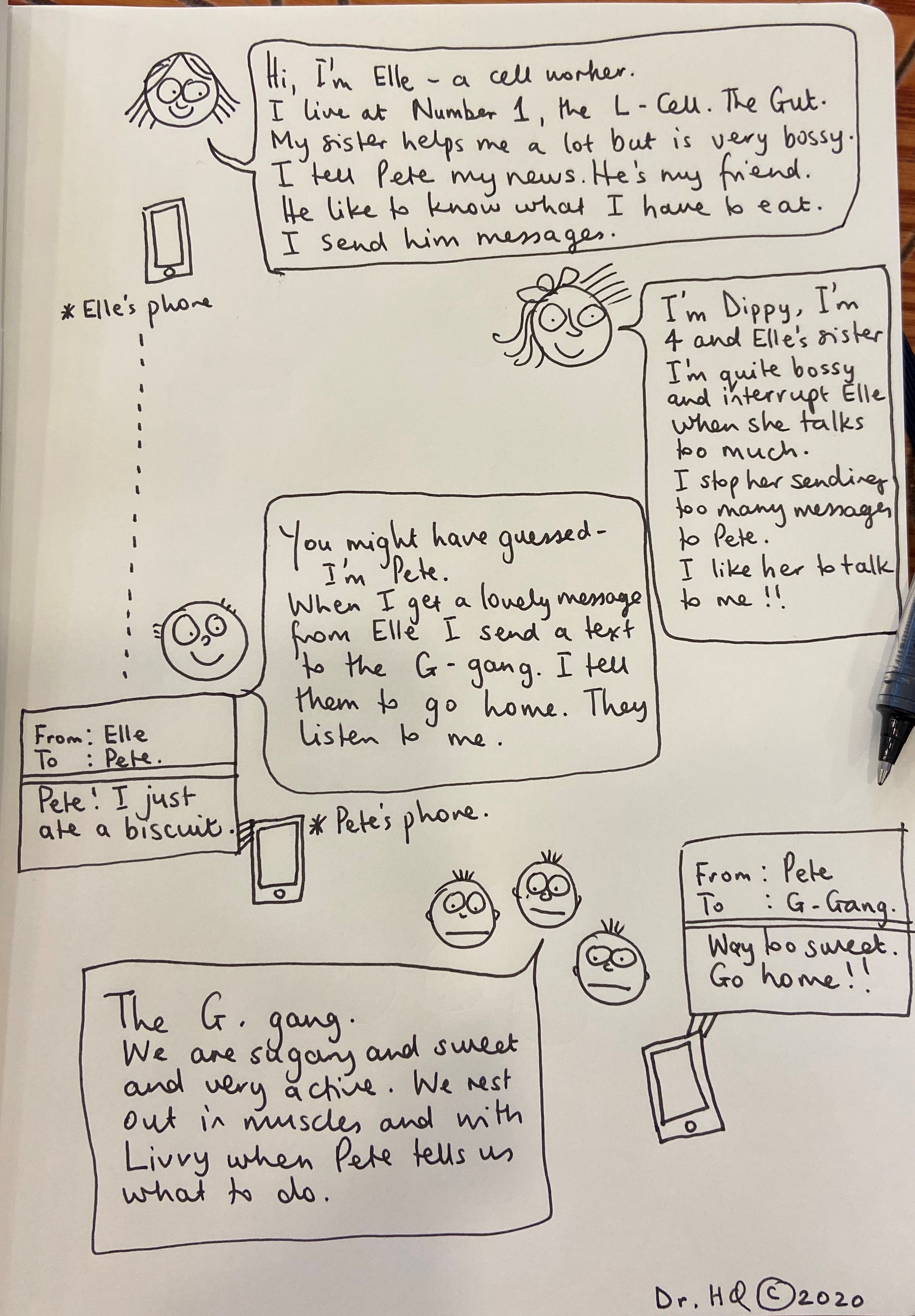

Before I studied medicine I attended the Glasgow School Of Art, reading Visual Communication. I was taught to consider what it was I wanted to say, and then work out how best to communicate it visually. This meant considering which material to use and to capture the spirit of the subject I was drawing using appropriately descriptive markings. This trained me to describe the essence of a concept or object and its function or position in the world. These principles can add value to a consultation as drawing supplements or contextualises the words we use. It can improve a patient’s understanding of physiology, pathology and pharmacology and reduce health anxiety; there is evidence that patient drawings can predict health outcomes and provide doctors with more insight into the patient experience6. Cartoons can be particularly helpful to explain pharmacology, particularly for those with limited literacy (Image 2). Colour is important – the red of an inflamed tympanic membrane, or a different colour to demonstrate a middle ear effusion. Just a few different pens can improve understanding.

My patients often ask to keep the drawings that I do (sometimes with the patient’s help) in a consultation as it represents their understanding of what was said. I see drawing as an adjunct in communication and possibly as a way to reduce complaints that can arise when patients feel that they have not been heard.

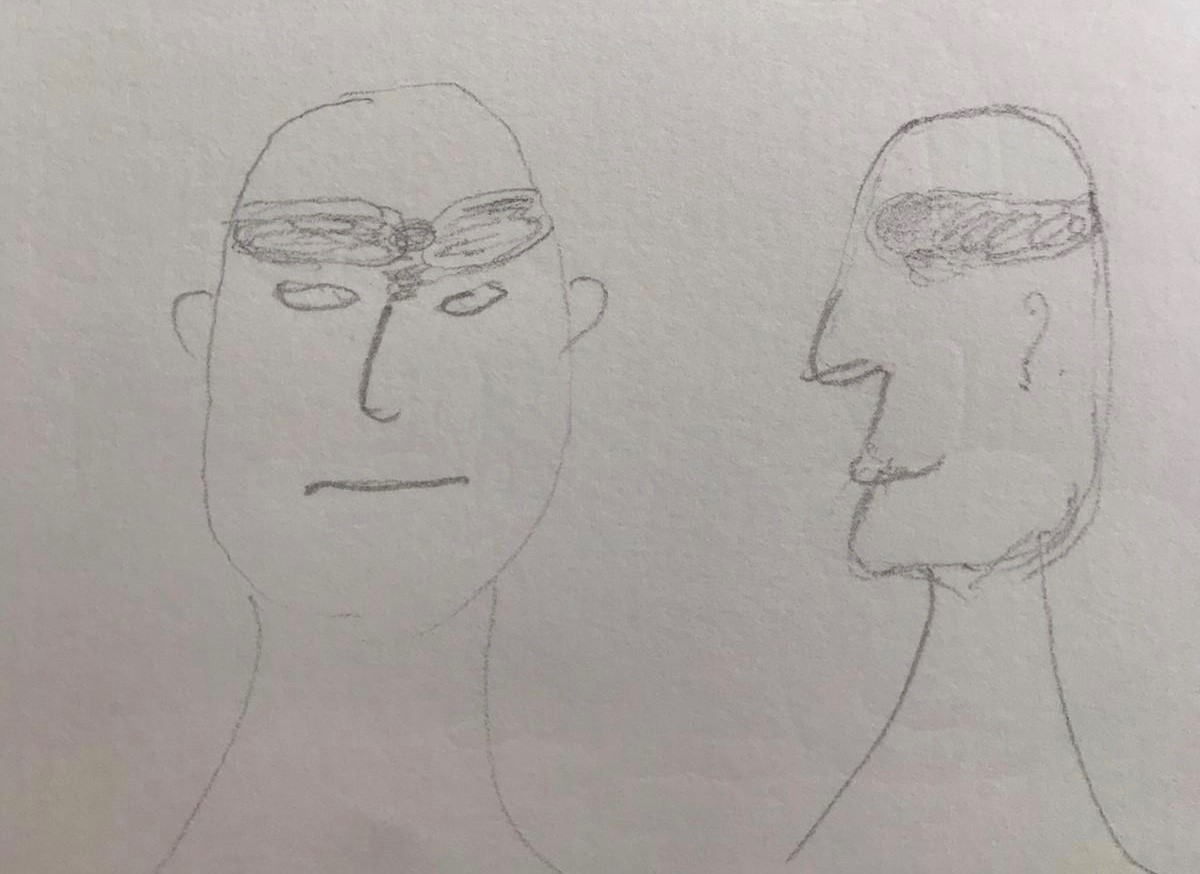

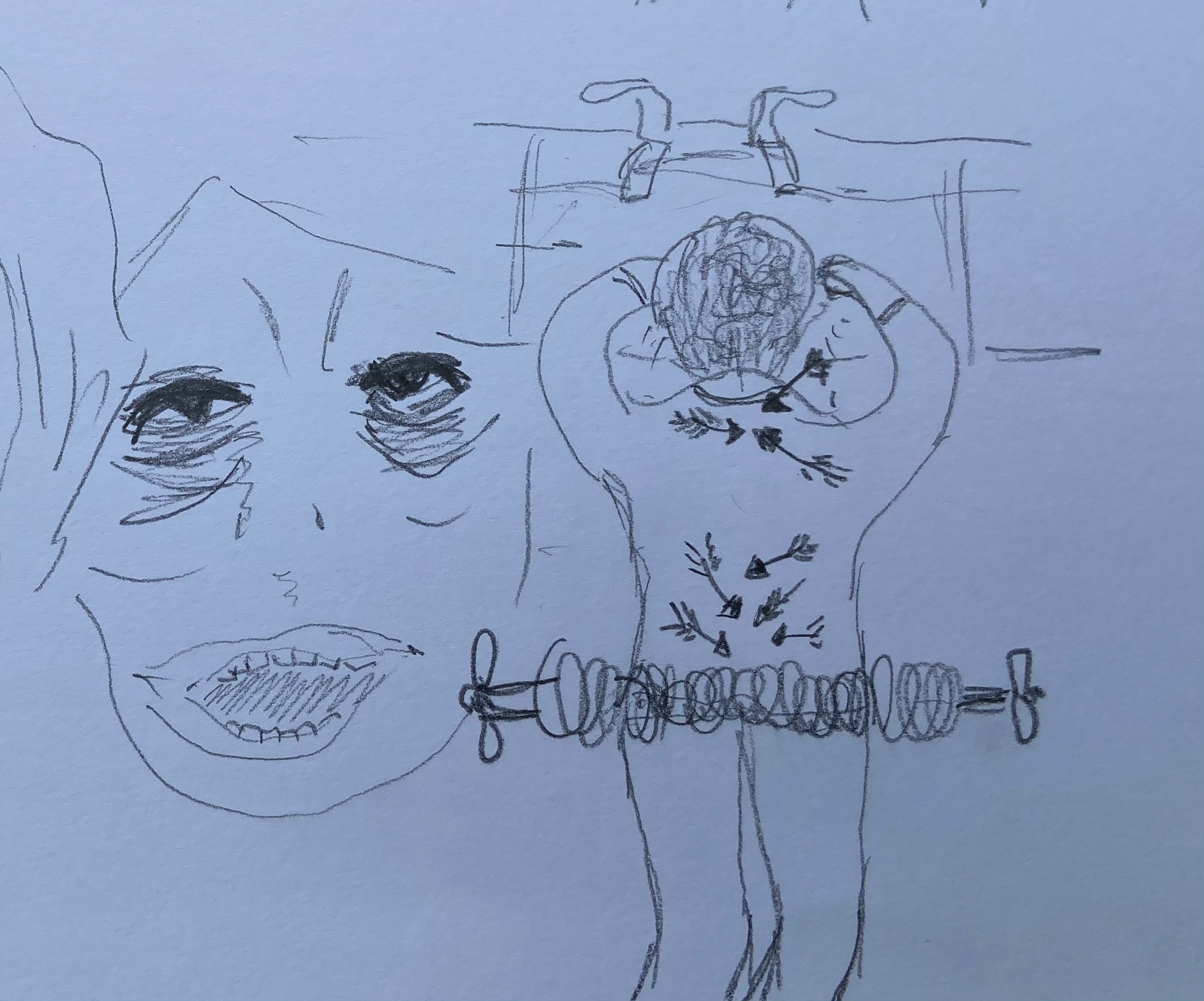

The use of images is not one-way as patients may add their own drawing, or bring pictures on their mobile device6. The following drawings (with patient permission) show personal representation of the pain experience in cluster headache (Image 3) and in these descriptive sketches (Image 4) the pain of end stage osteoarthritis with spondylolisthesis. Reference to the feeling of dragging and vice-like pain can be seen. I am not alone – there are other professionals using imagery in medicine.

Professor Gabrielle Finn fosters a network of artists, scientists, educators and health professionals interested in alternative methods of displaying by painting anatomical structures directly onto the body. She has kindly given permission for an image to be used here (Image 5). Her work crosses specialties and encourages innovative alternative approaches to learning.

The team around Professor Paul Rea, Professor of Digital and Anatomical Education at the University of Glasgow, created an animation explaining hypertension using clay models which simply describe concepts which are difficult to describe verbally.

Professor Alice Roberts, Professor of the Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham, uploads anatomical videos of embryological folding, and musculoskeletal anatomy, sometimes with the help of Jelly Babies.

In summary, at times there is a need in the doctor-patient consultation to change or extend the communication style. We can let our patients take over the pen to illustrate their concerns or symptoms. Good communication within the GP consultation and the use of alternative techniques to describe issues are valuable tools : sometime words fall short.

This blog was written by Dr Holly Quinton, GP and Illustrator. All images in this blog were provided by Holly with patients' consent. You can read more about Holly and visual consultations in the following BJGP article: How I use drawing and creative processes within the GP consultation.

References:

1Hall JA, Roter DL, Rand CSJ Health Soc Behav. 1981 Mar; 22(1):18-30

2Keenan I, Hutchinson J, Bell K, 2017, 'Twelve tips for implementing artistic learning approaches in anatomy education', MedEdPublish, 6, [2], 44, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000106

3 Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R, Buffone N, Lofton S, Wallace M, Goode L, Langdon L; Participants in the American Academy on Physician and Patient's Conference on Education and Evaluation of Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004 Jun;79(6):495-507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. PMID: 15165967.

4 Keenan I, Hutchinson J, Bell K, 2017, 'Twelve tips for implementing artistic learning approaches in anatomy education', MedEdPublish, 6, [2], 44, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000106

5 C Kotei: Metaphors in Medicine Synapsis Journal Oct 2017

6 Daeboudt, Broadbent, Berger & Kaptein, Lupus, 20,290-289