_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

No-one expects their child to die before them – it isn’t the natural order of things.

From miscarriages to stillbirths and from perinatal deaths to deaths in childhood, the death of a child is a unique type of loss.

Pregnancy loss is the most common form of child loss. It is currently estimated that one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage1 so it is something many parents will experience. Even though they may have never been able to get to know their child, they will still feel a huge loss. They grieve the potential to get to know that child and the life they would have had. Many parents will also feel a sense of guilt following a miscarriage so it is important to look out for any hint of this and to reassure the parent that this was not their fault.

When a parent loses a child of any age, in that split second, their world is changed forever. They lose not only their child, but also many of the social networks linked to their child. They lose the potential to see that child grow up and if the child was their only child, their identity as a parent and the chance to become a grandparent. They lose not only the present but also the future. The loss of a child for this reason is very different to other types of grief.

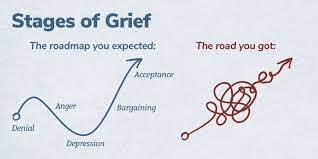

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

In 2007, Harper et al showed that in the 15 years after losing a child or having a stillbirth, bereaved mothers were 2-4 times more likely to die than non-bereaved mothers and that the excess risk persists for 35 years after the bereavement, though the magnitude of the risk drops with time. The increased risk persists for three years for fathers, though clearly they have an increased risk of being widowed for much longer. The reasons for this phenomenon are not clear, but could involve immunosuppression due to severe stress, maladaptive coping strategies such as alcohol misuse, pre-existing poor health which may have contributed to the child bereavement, mental ill-health following bereavement, or bereaved parents presenting later with their own physical health problems. Further research into this area would be useful. The relevance to general practice is probably that we should be aware of this risk and make particular use of the GP ‘spidey sense’ when dealing with this group of patients. Never ignore your gut feeling as a GP – it has been shown to be reliable3.

I am writing this blog from personal experience, after losing my four-year-old daughter Grace to cancer in 2014. My personal experiences have helped me to support many other families in similar situations and in 2018 I wrote an eLearning course for the RCGP, designed to provide GPs with the tools to support patients who have experienced a loss during pregnancy, or the death of an infant or child. Each family needs something different, but the overwhelming message is that having someone simply able to be there for them as a point of contact, it can make a big difference.

When a family loses a child, it also has a significant impact on their siblings. Life for their surviving siblings never returns to normal so it is important to remember that their bereavement will affect many aspects of their life and behaviour.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

Often, a few simple measures taken by a practice can make a sizable difference to help families realise that they are not alone. When the practice has been informed of a child death, it is important to contact the family, by phone if possible. This need only be brief, but families do appreciate this and remember this contact down the line.

Families should be provided with a named GP, and alerts placed on the notes of both parents and all siblings so practice staff and professionals can be aware of the history without the family needing to repeat themselves each time.

If possible, enable bereaved parents and siblings to make appointments at minimal notice for a limited time. The death of a child can plunge a family into chaos meaning things are easily forgotten or they may need to be seen quickly to help with acute emotional situations.

Ensure that all professionals are notified. Check that electronic alerts inviting the deceased child for immunisations, reviews or other routine care have been turned off. It is also useful to familiarise yourself with the services and support that are available in your local area to signpost families to as required.

General Practice is extremely busy at the moment, but these simple measures are relatively time efficient and can make a real difference to these families.

References

1 Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O'Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med, 1988; 319(4): 189-94.

2 Harper M, O'Connor RC, O'Carroll RE. Increased mortality in parents bereaved in the first year of their child's life. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2011; 1(3): 306-9.

3 Friedemann Smith C, Drew S, Ziebland S et al. Understanding the role of GPs’ gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. British Journal of General Practice 2020; 70 (698): e612-e621.

'Stages of Grief' image used with permission from WPSU's Speaking Grief project.