_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

The majority of people, including health care professionals (HCPs), have unconscious or implicit biases1. These can affect the way we interact with colleagues, staff and patients, and even influence our decision making in regards to diagnosis and management of conditions2.

Unconscious bias is the immediate judgement of something, or someone, based on our past experience, background and culture. It is instinctive rather than a rational thought process and occurs almost instantaneously on encountering someone new. This bias can then influence our thoughts, beliefs and behaviour towards that person.

When we first meet someone, we subconsciously categorise them based on, for example, their gender, age, skin colour, accent, profession, sexual orientation3. We then use preconceived ideas of their intrinsic characteristics and form an immediate opinion about the person. Most people have unconscious biases, no matter how strongly they consciously oppose discrimination or prejudice. We tend to feel positively about someone who is similar to us, and negatively about those we perceive as ‘different’. These assumptions then effect the relationship we have with that person, including how close we will stand to them, and how often we make eye contact2.

The term unconscious bias encompasses several types of bias such as gender bias, confirmation bias, age bias, and affinity bias, to name a few. These biases can affect everything from to which candidate we would offer a practice vacancy, to how we manage different patients with the same condition. It can be both positive and negative, as we may favour or disapprove of someone based on whether we feel they fit into ‘our group’ (namely, whether we feel they share similar characteristics to us).

Take a vacant salaried GP position as an example: You’re on the interview panel. The next applicant trained at the same medical school and enjoys the same hobbies as you. You immediately think ‘yes, this person is great’. The next applicant attended a rival medical school and has different hobbies; you’re not so sure about this applicant. This is an example of affinity bias. These opinions are formed without us even realising it and without taking into account the person’s qualifications or experience. Once that initial judgement is formed, our brain then begins to gather evidence to support our assessment. However, this ‘evidence’ is also biased (confirmation bias) as we look for anything that will uphold our initial decision and disregard items that refute it.

Unconscious bias is well recognised in the interviewing process, and many private companies have procedures in place to reduce the risk of this happening4. But how does this translate into the world of healthcare?

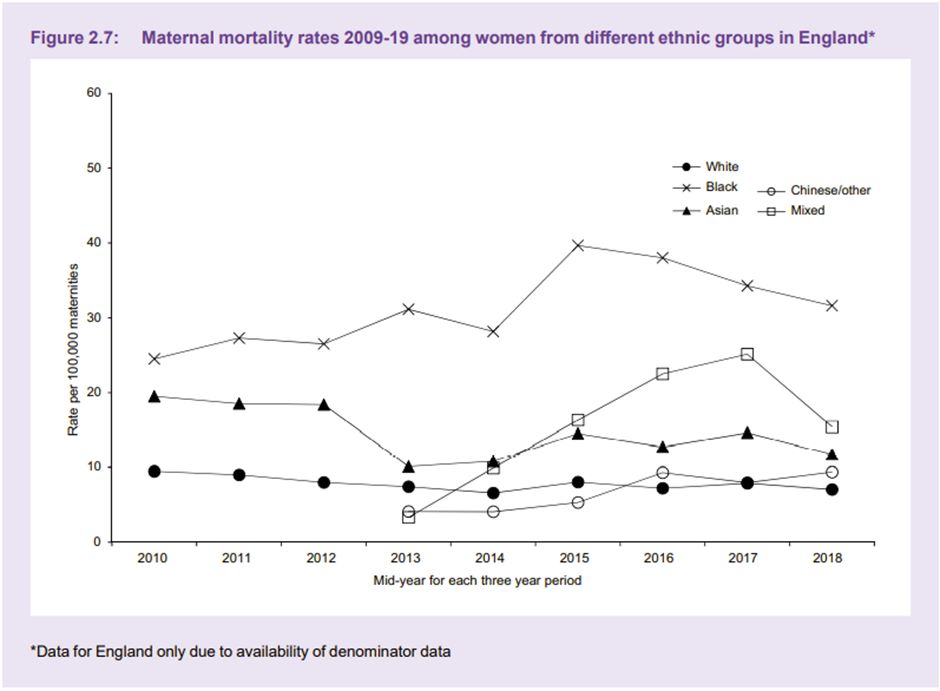

Unconscious bias may have a significant impact on medical school admissions, with one American study reporting a notable race bias5 by those on the selection panel. International medical graduates (IMGs) are up to thirteen times more likely to be referred to the GMC than UK graduates6, which is thought to be due, at least in part, to unconscious bias. We commonly hear of female doctors being called nurse whilst male nurses or medical students are called doctor and are often talked to in preference to their senior female colleague.Not only does unconscious bias affect us and our colleagues, but it also has a crucial and concerning impact on our patients. In 2021 Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risks through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK (MBRRACE-UK) released a report7 that showed black women were four times more likely to die in pregnancy than white women. Whilst socioeconomic factors and medical reasons were thought to contribute to the outcomes, this only accounted for a small proportion of women. Black women report not being listened to or empathised with as much as their white counterparts8.

Graph from MMBRACE-UK 'Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19'. Used with permission from MMBRACE-UK.

Several studies have shown that there is racial bias in regards to pain management, with black people frequently denied analgesia that their white counterparts are readily offered. Research by Hoffman et al (2016) reported that the false belief of biological differences between white and black people contributing to pain thresholds, are held by the general population, and more worryingly by medical students and qualified doctors9. This not only impacts women in labour, but all situations where adequate pain relief is important.

The Midlands Leadership Academy has developed an Unconscious Bias Toolkit10 which suggests several ways in which we can challenge our own unconscious biases. The toolkit advises us to consider:

- What am I thinking?

- Why am I thinking it?

- Is there a past experience that is impacting my current decision?

- Is the past experience applicable now or is it based on a preference or bias?

Furthermore, the Royal Society4 advise that we should slow down when making decisions, reconsider reasons for decisions, question cultural stereotypes and monitor each other for unconscious bias. The Royal College of Surgeons have published a document on reducing unconscious bias11 in which they suggest using Thiederman’s Seven Steps for defeating bias in the workplace.

|

1. Become mindful of your biases 2. Put your biases through triage 3. Identify the secondary gains of your biases 4. Dissect your biases 5. Identify common kinship groups 6. Shove your biases aside 7. Fake it till you make it (what we say can become what we believe) |

Medical education - whether undergraduate or postgraduate - has a responsibility to promote curricula in a non-biased way. There has recently been a push to decolonise medical education and incorporate cultural safety12: Decolonising medical education involves challenging beliefs and introducing ‘new normals’ such as representing signs and symptoms of illnesses in different skin tones; or promoting issues faced by discriminated groups, for example, including violence against women and racism in curricula13. Cultural safety is a concept developed by Māori Nurse Educator Irihapeti Merenia Ramsden, who recognised the health inequalities between indigenous and non-indigenous people in New Zealand. Cultural safety is to understand that health inequality is based on historical prejudice, and using lived experiences of those who have experienced discrimination ensures that differences in culture are respected throughout healthcare. If health care professionals and students understand how conditions may present in different ethnicities and genders, really listen to patients experiences and concerns regardless of their skin colour or own beliefs, and learn to challenge their unconscious bias, then hopefully we will develop a generation of healthcare professionals who can more fully appreciate and challenge health inequality in the UK.

The RCGP has recently launched an interactive eLearning module on Allyship, which includes information and suggested actions to promote anti-racism and bystander intervention. You can access the course here: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/allyship

References

- Schwarz, J., 1998. Roots of unconscious prejudice affect 90 to 95 percent of people, psychologists demonstrate at press conference, University of Washington, [online]. Available at: https://www.washington.edu/news/1998/09/29/roots-of-unconscious-prejudice-affect-90-to-95-percent-of-people-psychologists-demonstrate-at-press-conference/ [Accessed 06 April 2022]

- FitzGerald, C. and Hurst, S., 2017. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8.

- Rice, M., 2015. Unconscious bias and its effect on healthcare leadership. Healthcare Network, The Guardian. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2015/may/19/healthcare-leadership-best-practice-unconscious-bias. [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Frith, U., 2015. Understanding Unconscious Bias. The Royal Society. [online] Available at: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2015/unconscious-bias/?gclid=CjwKCAiA6seQBhAfEiwAvPqu18TssncdweUmNPHBiUb8o2UHBslILV8UOvM-fs7ePvbngXtmq6fdrRoC-PYQAvD_BwE. [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Capers, Q., 4th, Clinchot, D., McDougle, L., and Greenwald, A. G., 2017. Implicit Racial Bias in Medical School Admissions. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92(3) pp.365–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

- Rimmer A, 2017. Unconscious bias must be tackled to reduce worry about overseas trained doctors, says BAPIO. British Medical Journal, 357 :j1881 doi:10.1136/bmj.j1881.

- Knight, M., et al on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19. [online] Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2021. Available at: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2021/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2021_-_FINAL_-_WEB_VERSION.pdf [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Brathwaite, C., 2018. Black Mothers Are Disproportionately More Likely To Die In Childbirth - We Need To Address The Race Gap In Motherhood. Huffington Post [online] Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/race-motherhood-black-mothers-dying-childbirth_uk_5c078da3e4b0a6e4ebd9d5ec [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Hoffman, K.M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J.R., and Oliver, M.N., 2016. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), pp.4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.

- Masuwa, P. and Sharma, M. Unconscious bias toolkit. NHS Midlands Leadership Academy. [online] Available at: https://midlands.leadershipacademy.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/12/Unconscious-bias-toolkit-final-version.pdf.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2016. Avoiding Unconscious Bias: A guide for surgeons. [online] London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England (Published 2016) Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/rcs-publications/docs/avoiding-unconscious-bias/ [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Wong, S.H.M., Gishen, F. and Lokugamage, A.U., 2021. ‘Decolonising the Medical Curriculum‘: Humanising medicine through epistemic pluralism, cultural safety and critical consciousness. London Review of Education, 19(1). DOI: 10.14324/LRE.19.1.16.

- Lokugamage, A.U., Ahillan, T. and Pathberiya, S.D.C., 2020. Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics 46(4), pp.265-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866.