_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

It is now over 40 years ago since a rare lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii was noticed in five young, previously healthy men who lived in Los Angeles1. The article describing this cluster or cases was the first hint of a global epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which at the time led inexorably to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and almost certain death.

Fast forward to 2022 and HIV has become a treatable chronic disease – those who are adherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART) with an undetectable viral load can expect a normal or near-normal life span2 and no longer have to worry about passing the virus to a sexual partner, as this is impossible for those on effective treatment3.

The most important factor in reducing morbidity and mortality is early diagnosis and early initiation of ART. Progress of the virus is measured by monitoring the viral load and CD4 count (a type of T lymphocytes). If HIV is diagnosed late (when the CD4 count has dropped below 350 cells/mm3), there is a ten-fold increase in risk of the patient dying in the year after diagnosis4,5 and if this doesn’t happen, they still have a likely ten-year reduction in life expectancy2. It is estimated that 6,600 people in England have undiagnosed HIV, making up approximately 6% of the total population of people with HIV in England6. This group will have a poor prognosis if they remain undiagnosed, and risk unknowingly passing the virus to their sexual partners.

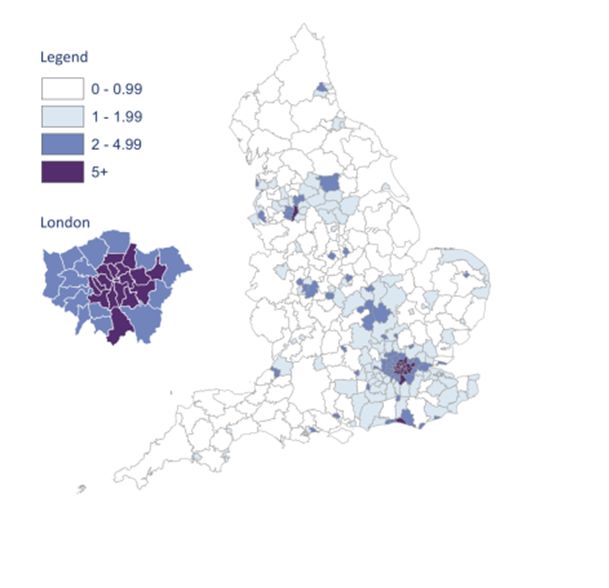

NICE guidance advises that we offer and recommend HIV testing based on local prevalence, which can be seen on this map of diagnosed HIV prevalence per 1,000 population aged 15 – 59 years in England in 2015. There are hotspots of high prevalence (2-5 cases per 1,000) and extremely high prevalence (>5 cases per 1,000) in various cities including London, Brighton and Manchester – healthcare professionals in these areas should be aware of the recommendation to offer routine HIV tests as laid out in the table below7, which also covers the clinical situations in which any healthcare professional should offer a test, regardless of local prevalence.

Map from HIV in the UK 2016 Report, Public Health England8

Image used under the Open Government Licence v3.0

|

Prevalence level |

When to offer a test |

|

High |

|

|

Extremely high |

|

|

Any prevalence |

|

In primary care we should be aware that HIV may present at seroconversion, or later as the CD4 count drops and symptoms of immunodeficiency start to emerge.

Seroconversion occurs between 10 days and six weeks after infection with HIV and may be very mild. It is difficult to diagnose as clinical features can be non-specific, including a fever, sore throat, malaise and arthralgia. A maculopapular rash, particularly in combination with a fever, should alert us to the possibility of seroconversion2. Traditionally we have considered there to be a 12 week ‘window period’ for HIV testing – the time in which a person may have contracted HIV, but still have a negative test as they have not yet made enough antibodies for the test to be positive. Many labs now use combined antibody/antigen tests which shorten the window period, but unless you are familiar with the tests used locally, it is safest to advise that anyone who may be in the early stages of HIV repeats their test at least 12 weeks after any encounter where they think they may have caught the virus.

Later symptoms are listed in the British HIV Association list of ‘clinical indicator diseases’, which are defined by the fact that patients with these conditions have at least a 1 in 1000 likelihood of having undiagnosed HIV9. They include diagnoses and incidental findings which are commonly seen in general practice, such as unexplained fever, lymphadenopathy, chronic diarrhoea or weight loss, unexplained low white cell count or platelet count and any cervical dysplasia or community acquired pneumonia. We should also consider testing for various skin conditions, including seborrhoeic dermatitis, shingles and severe psoriasis, and for those with lung cancer or lymphoma.

It is not all that often that we can point to a specific consultation in primary care and say “I saved a life today”. Picking up a case of HIV and getting a patient on to antiretrovirals is a truly life-saving measure, for which an increase in testing is vital.

References (all accessed 9.10.22)

1. HIV.gov. A timeline of HIV and AIDS. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline#year-1981

2. NICE CKS. HIV infection and AIDS. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hiv-infection-aids/

3. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. HIV Undetectable=untransmissible, or Treatment as Prevention. 2019. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/treatment-prevention

4. The Lancet HIV. Time to tackle late diagnosis. Lancet HIV. 2022 Mar;9(3): e139

5. UK Health Security Agency. Leaving it late: why are people still dying from HIV in the UK? 2014.

6. Public Health England. Trends in HIV testing, new diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2019. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/959330/hpr2020_hiv19.pdf

7. NICE NG60. HIV testing: increasing update among people who may have undiagnosed HIV. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng60/chapter/Recommendations#offering-and-recommending-hiv-testing-in-different-settings

8. Public Health England. HIV in the UK 2016 Report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/602942/HIV_in_the_UK_report.pdf

9. British HIV Association. British HIV Association/British Association for Sexual Health and HIV/British Infection Association Adult HIV Testing Guidelines 2020. 2020. Appendix 1. https://www.bhiva.org/file/5f68c0dd7aefb/HIV-testing-guidelines-2020.pdf