_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

The Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the most common cause for

acute viral hepatitis worldwide, a fact that is not widely known in the United

Kingdom. It is a small RNA virus that has various genotypes, though the most

important are HEV 1&2 – the most common types in low-income countries – and

HEV 3, which occurs in Europe, the Americas and Australia.

HEV is responsible for about 20 million infections worldwide each year, of which 3 million will be symptomatic and 56,000 lethal. In the United Kingdom, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) follows up confirmed Hepatitis E infections to investigate non-travel related cases of HEV in England and Wales while Public Health Scotland (PHS) monitors HEV infections within their territory.

HEV 1&2 are obligate human pathogens and usually transmitted faecal – orally by contaminated drinking water, while HEV 3 is usually transmitted via inadequately cooked pork, molluscs, or seafood. 90% of pigs in the UK have antibodies to HEV, and around 20% have been known to have an active infection at the time of slaughter. Within Europe the prevalence varies, though there are geographic hotspots with human seroprevalence of >50%. In 2019, UKHSA reported 1202 confirmed HEV infections, PHS reported 158 (>100 cases more than Hepatis A) though due to its often asymptomatic nature, it is reported to be significantly underdiagnosed.

The presentation of acute HEV infections depends on the location of the patient and the genome responsible: In resource poor countries it usually affects young people 15-35 years of age who experience an acute, self-limiting hepatitis due to HEV1 (Asia) or 2 (Central America). Preterm women are particularly affected, with papers quoting mortality rates of up to 25% and preterm deliveries in 66%.

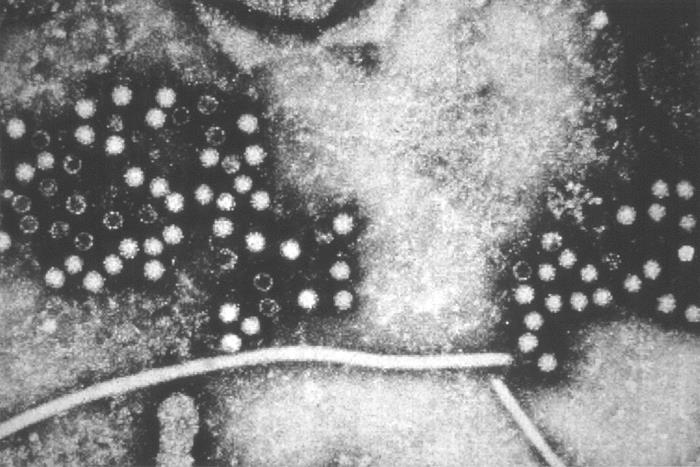

This transmission electron micrograph depicts numerous, spheroid-shaped, hepatitis-E viruses (HEV), also known as Orthohepevirus A. Image used with permission from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

• ALT > 300 IU/L

• Clinical suspicion of drug

induced liver injury

• Decompensated chronic liver

disease (regardless of LFT results)

• Guillain–Barré syndrome

(regardless of LFT results)

• Neuralgic amyotrophy (regardless

of LFT results)

• Patients with unexplained acute

neurology and a raised ALT

During the first 2 weeks of hepatitis E illness:

- avoid preparing food for others

- limit contact with others if possible, especially pregnant women, or people with chronic liver disease

- wash hands thoroughly with soap and warm water and then dry properly after contact with an infected person

- wash hands after going to the toilet, before preparing, serving and eating food

Pregnant women should contact their obstetric team for advice.

As there is currently no licensed vaccine for Hepatitis E in the United Kingdom, prevention is key. UKHSA suggests:

- cooking meat and meat products thoroughly

- avoid eating raw or undercooked meat and shellfish

- washing hands thoroughly before preparing, serving and eating food.

When travelling to countries with poor sanitation:

- boil all drinking water, including water for brushing teeth

- avoid eating raw or undercooked meat and shellfish.

In primary care, a good travel history can be key to diagnose a patient with an unexplained rise in liver function tests and prodromal symptoms.

References:

Aslan, TA; Balaban, HY (2020). Hepatitis E virus: Epidemiology, diagnosis, clinical manifestations, and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology. October 7; 26(37): 5543-5560

Horvatits, T; Schulze zur Wisch, J et al. (2019). The clinical perspective on Hepatitis E. Viruses 11, 617

Public Health Scotland: Ten-year gastrointestinal and zoonoses data tables (2023). https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/ten-year-gastrointestinal-and-zoonoses-data-tables/ten-year-gastrointestinal-and-zoonoses-data-tables-march-2023/ (Accessed 15.08.2023)

UKHSA: Hepatitis E: symptoms, transmission, treatment and prevention (2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-e-symptoms-transmission-prevention-treatment/hepatitis-e-symptoms-transmission-treatment-and-prevention (Accessed 15.08.2023)

Webb, GW; Dalton, HR (2019). Hepatitis E: an underestimated emerging threat. Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease Vol. 6: 1–18