_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

Written by Dr Emma Nash

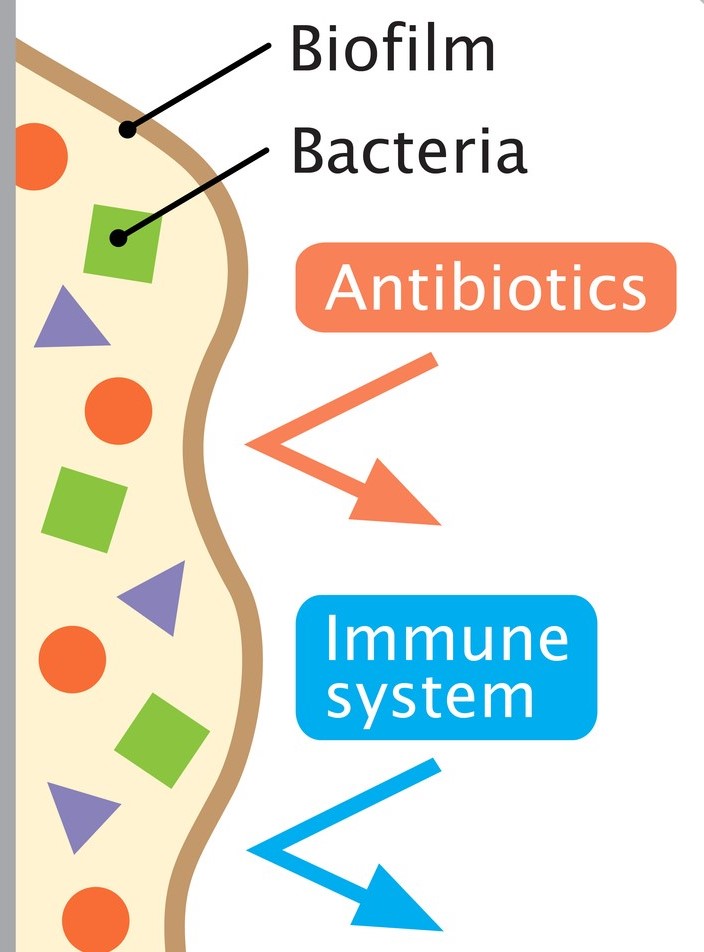

Cough is one of the most frequent reasons for presentation to primary care, particularly in children. Acute cough is most commonly caused by upper respiratory tract infections; chronic cough (over four weeks) is typically attributed to recurrent respiratory tract infection, asthma or pertussis. However, a wet cough lasting more than four weeks should prompt consideration of protracted bacterial bronchitis, also known as persistent bacterial bronchitis (PBB). First described in a study in 2006, the condition is being increasingly recognised clinically. However, there is no clarity on the underlying mechanisms, making definitive diagnostic and therapeutic guidance elusive. Proposed pathophysiological contributory factors include impaired mucociliary clearance, systemic immune function defects (raised NK-cell levels, altered expression of neutrophil-related mediators), and airway anomalies (tracheobronchomalacia). It is also thought that bacteria may produce a biofilm in the airways. This is a secreted matrix that enhances bacterial attachment to cells and facilitates access to nutrients. It also decreases antibiotic penetration, thus protecting the bacteria and making them harder to eradicate with standard length courses of treatment.

PBB is initially difficult to distinguish from a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The cough is productive, but the child is systemically well. Although wheeze is variably reported, the evidence is that there is a limited response to bronchodilator therapy, if any. Chest examination is typically normal, but if a wheeze is heard, it is monophonic rather than the polyphonic wheeze found in asthma. Sinus and ear disease is absent.

PBB is a clinical diagnosis. It may be suspected when the first two of the European Respiratory Society criteria are met, and confirmed when all three are met:

1. Presence of continuous chronic wet or productive cough (>four weeks’ duration).

2. Absence of symptoms or signs suggestive of other causes of wet or productive cough (see box 1).

3. Cough resolved following a two-to-four-week course of an appropriate oral antibiotic.

|

Box 1:

Pointers suggestive of causes other than PBB.

|

The median age of development is 10 months – 4.8 years and it affects more males than females. PBB is no more common in children with an atopic history, but one study has shown that children who attend childcare are significantly more likely to develop PBB than those who do not. Children with an airway malacia are at increased risk of developing the condition as it is harder to clear mucus when the airways tend to collapse. If this is an underlying factor for a particular child, giving a bronchodilator may exacerbate the symptoms as the airways relax even further. PBB is frequently misdiagnosed, or inadequately treated, resulting in a persistence of symptoms and potential structural damage in the form of bronchiectasis.

Most children who have PBB are not able to expectorate sputum for culture due to their age, so treatment is based on the sensitivity profiles of the typical pathogens. Haemophilus influenzae is the most common causative organism, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. However, sputum culture should be sent, if feasible.

Previously, antibiotic treatment courses have been longer, and there has been much debate over optimal drug choice and duration. More recent evidence has shown that two weeks may be adequate in many cases. A further two weeks should be prescribed if the child has improved significantly but is not completely cough free. A minority will need longer courses, but if this is the case, there should be a high index of suspicion for more severe disease such as chronic suppurative lung disease (e.g. cystic fibrosis) or bronchiectasis. Therefore, failure of the cough to respond to four weeks of antibiotics should prompt discussion with a paediatrician for consideration of next steps and whether investigation is needed for underlying causes. A reasonable pathway in primary care would therefore be that a GP suspects PBB because the first two criteria are met, treats with two weeks of antibiotics (and a further two if there is no improvement) and then seek specialist advice if the cough persists after four weeks of antibiotics. Chest x-ray is generally only needed if there is a specific reason, such as focal chest signs of concern.

Previously, antibiotic treatment courses have been longer, and there has been much debate over optimal drug choice and duration. More recent evidence has shown that two weeks may be adequate in many cases. A further two weeks should be prescribed if the child has improved significantly but is not completely cough free. A minority will need longer courses, but if this is the case, there should be a high index of suspicion for more severe disease such as chronic suppurative lung disease (e.g. cystic fibrosis) or bronchiectasis. Therefore, failure of the cough to respond to four weeks of antibiotics should prompt discussion with a paediatrician for consideration of next steps and whether investigation is needed for underlying causes. A reasonable pathway in primary care would therefore be that a GP suspects PBB because the first two criteria are met, treats with two weeks of antibiotics (and a further two if there is no improvement) and then seek specialist advice if the cough persists after four weeks of antibiotics. Chest x-ray is generally only needed if there is a specific reason, such as focal chest signs of concern.

Unfortunately, no nationally accepted guidelines exist on treatment choice. The most commonly used antibiotic is oral co-amoxiclav but alternatives such as oral second or third generation cephalosporins, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a macrolide may be used when there is a history of an IgE-mediated reaction to penicillin.

It is worth noting that recurrent episodes are common, occurring in up to 76% of cases. Antibiotic prophylaxis may be helpful in children who have more than three recurrences in twelve months. Common choices for prophylaxis are azithromycin three days a week, or co-trimoxazole daily, but this would be on specialist advice.

References

American Thoracic Society. Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis (PBB) in Children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 198, P11-P12. View patient education sheet on Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis (PBB) in Children. [accessed 20 March 2024]

Bergmann M, Haasenritter J, Beidatsch D, et al. Coughing children in family practice and primary care: a systematic review of prevalence, aetiology and prognosis. BMC Pediatr. 2021 Jun 4;21(1):260.

Di Filippo P, Scaparrotta A, Petrosino Mi et al. An underestimated cause of chronic cough: The Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis. Ann Thorac Med. 2018 Jan-Mar;13(1):7-13.

Kansra S. Diagnosis and Management of Children with Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis PBB. Sheffield Children’s Hospital NHS Trust. 2017. Download guideline on Diagnosis and Management of Children with Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis PBB. [accessed 20 March 2024]

Kantar A, Chang A, Shields MD, et al. ERS statement on protracted bacterial bronchitis in children. European Respiratory Journal 2017 Aug; 50(2):1602139.