_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

Introduction

Mpox (previously known as monkeypox) is a viral, infectious disease caused by a strain of the monkeypox virus (MPXV). The first human cases were identified in 1970 in the rainforest areas of Central and West Africa. Until 2022, outbreaks were usually limited to this geographical area, with occasional imported cases into non-epidemic countries and human to human transmission only present in a limited number of cases.

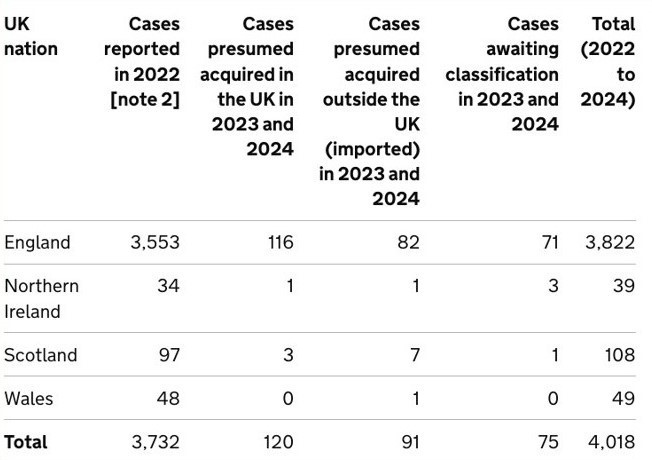

MPXV has two distinct genetic lineages, called clade 1 and 2, both split into types a and b. The 2022-2023 global outbreak of mpox that continues to this day is due to clade 2b and caused 3,822 cases in the UK over the last two years.

The 2022-23 outbreak was driven by human to human MPXV transmission via close contact with infected individuals and continues to this day, albeit in lower levels and particularly among men who have sex with men. In 2024, clade 1b mpox cases were starting to spread outside its traditional geographical location in West Africa with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Cameroon and Gabon all affected and around 20,000 cases and potentially 1000 deaths reported in the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone. On 14th August 2024 the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency over mpox and since then two imported cases have been identified in Sweden and Thailand.

Transmission

Mpox is transmitted through skin to skin contact, inhalation or contact with mucous membranes, through direct contact with skin lesions, coughing and sneezing and contact with clothing or linen used by person with mpox. Sexual contact, kissing, cuddling or other skin-to-skin contact can all cause transmission.

Signs and symptoms

While short incubation periods have been reported, a contact tracing study from the United Kingdom showed that 95% of people with a potential infection had symptoms within 16-23 days. There have been reports that clade 1b might have a shorter incubation record, but there remains a significant degree of uncertainty. Typical prodrome of the illness are fever, headache, myalgia and joint pain and lymphadenopathy, but proctitis and sore throats have also been reported. In the 2022-23 outbreak the subsequent rash was usually limited to fewer than 20 lesions, but there is anecdotal evidence that the rash associated with clade 1b is more severe with up to several thousand pustules. Similarly, mortality seems to be increased in the new outbreak, though this might be due to the affected population being more vulnerable. The rash initially presents with macules, before developing into papules, vesicles, pseudo-pustules containing solid debris, crusts, and finally scabs, before falling off within 7–14 days. These can be painful and are often located orally or in the genital or anorectal areas.

Mpox lesions in various stages of progression. UKHSA. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Management

Making a diagnosis of mpox can be difficult, as there is a broad range of differential diagnoses for pyrexial maculopapular viral rashes such as chickenpox, measles, bacterial skin infections, scabies and herpes. A travel, contact and sexual history is important to narrow the possible diagnosis down.

If triaging a patient with suspected mpox or if a patient presents with suspected mpox in general practice, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) suggests isolating the patient in a single room and contacting the local infection service for advice, including appropriate arrangements for transfer into secondary care and immediate precautions in the setting (and who will manage contract tracing and advise on vaccination). When examining a suspected patient, clinical staff should wear face fit tested FFP3 masks, eye protection, long-sleeved splash resistant gowns and gloves to provide care if immediately required.

Treatment is usually symptomatic, but there are antivirals available in secondary care for those with severe disease or immunocompromised patients. The UKHSA has released guidance for pre- and post-exposure vaccination with the smallpox vaccine for patients, contacts and healthcare workers (see references).

References

Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). Africa CDC Epidemic Intelligence Weekly Report, August 2024. [accessed 2 September 2024].

Branda F, Romano C, Ciccozzi M, et al. Mpox: An Overview of Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Public Health Implications. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 12;13(8):2234.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical Recognition: Key Characteristics for Identifying Mpox. Aug 2023. [accessed 2 September 2024].

Center for Health Security Johns Hopkins University. Situation Update Mpox Virus: Clade I and Clade IIb. 2024. [accessed 2 September 2024].

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Factsheet for health professionals on mpox. Aug 2024. [accessed 2 September 2024].

Reardon S. Mpox is spreading rapidly. Here are the questions researchers are racing to answer. Nature. 2024 Sep;633(8028):16-17.

UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Clade I mpox virus infection. Aug 2024. [accessed 2 September 2024].

UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Mpox: background information. Aug 2024. [accessed 2 September 2024].

UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Recommendations for the use of pre-and post-exposure vaccination during a monkeypox incident. Aug 2022. [accessed 2 September 2024].

World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox. Aug 2024. [accessed 2 September 2024].