_ RCGP Learning

Blog entry by _ RCGP Learning

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) - whether it presents as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) - is a common presentation in primary care: its annual incidence is 1-2 cases per 1000 population, rising significantly with increased age. In Europe, pulmonary embolism accounts for 8–13 deaths per 1000 women and 2–7 deaths per 1000 men aged 15–55 years1. Thrombosis UK suggests that 1 in 20 people will experience a VTE in their lifetime2. NHS Resolution reports that from 1 April 2012 until 31 March 2022 it documented 687 closed claims relating to VTE injuries across the clinical negligence indemnity schemes, with total damages paid of £23,780,1793.

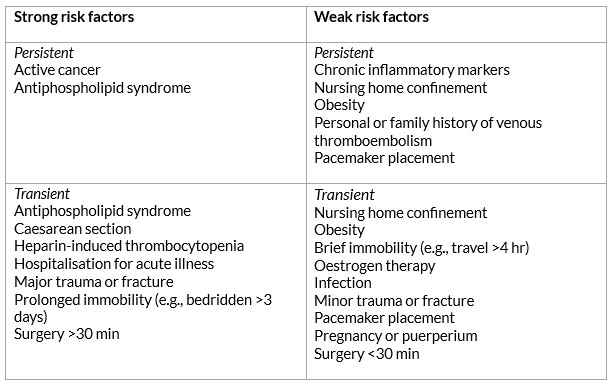

Significant risk factors such as major surgery, prolonged immobilisation, and major trauma account for approximately 20% of all venous thromboembolism episodes, though the commonest strong persistent risk factor is active cancer, accounting for approximately 20% of incidents. Table 1 lists persistent and transient risk factors for VTE.

Table 1: Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, Rodger MA. Venous thromboembolism. The Lancet 2021 Jul; 398(10294): 64–77.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with a deep vein thrombosis can present with leg pain (80–90% of patients), swelling (80%), localised tenderness on palpation (75–85%), prominent collateral superficial veins (30%) and redness (25%). 30% - 60% of patients presenting with a proximal (above the knee) DVT already have a silent pulmonary embolism. A review paper from Canada described that the majority of symptomatic episodes of lower extremity DVTs start in the distal veins, with symptoms being uncommon until there is involvement of the proximal veins. They reported that in a consecutive series of 189 outpatients with a first episode of venographically diagnosed DVT, where symptoms were all distal, 89% had proximal thrombi4. Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT) – arising in the brachial, axillary or subclavian veins - is thought to account for about 10% of all DVTs5.

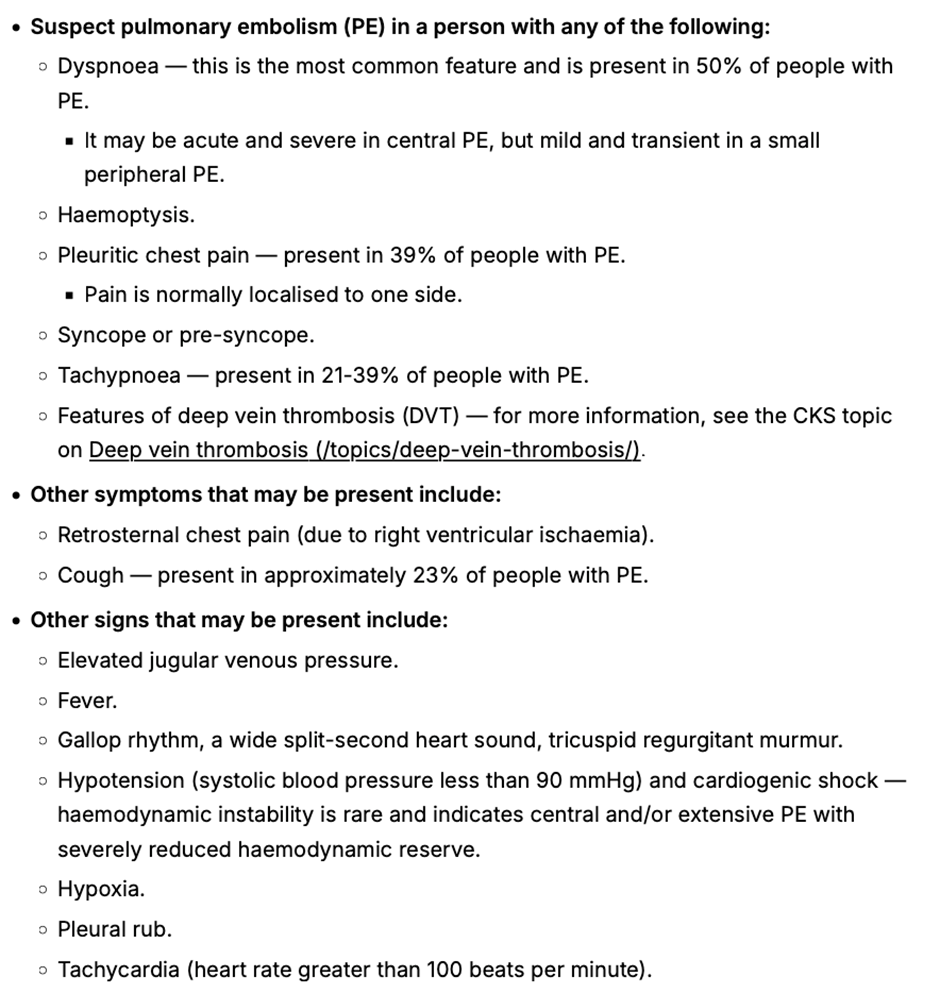

Pulmonary emboli often present insidiously and often without the classic triad of pleuritic chest pain, shortness of breath and hypoxia. There are a large number of case reports showing patients complaining of nagging symptoms for weeks before succumbing to pulmonary embolism, with 40% of these patients being seen by a physician in the weeks prior to their death6. A retrospective cohort study from 2016 showed that 25% of patients with a PE presenting in primary care had an average delay of 15.7 days to diagnosis7. Table 2 lists the range of symptoms that the NICE CKS suggests point towards a PE.

Table 2: When to suspect pulmonary embolism from NICE CKS Pulmonary embolism 2023.

Diagnosis

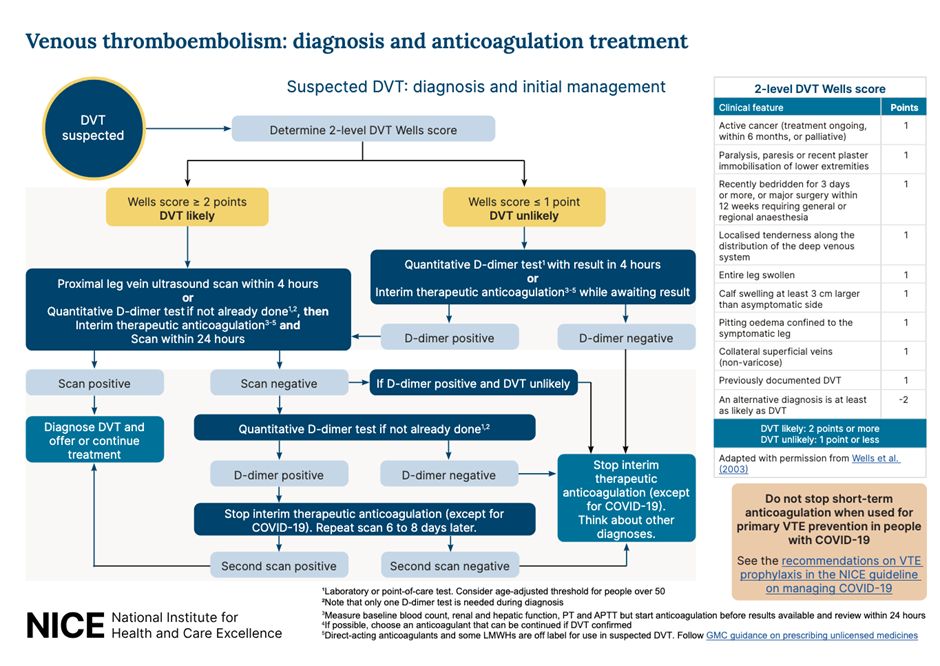

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updated their recommendations for the diagnosis and management of VTE in 2023. It suggests that patients with symptoms that might indicate a DVT should be examined and accessed via a 2 - level Wells Score. If the Wells score is 2 or above, these patients should be offered a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan, with the result available within 4 hours if possible. If the scan is negative, a D-Dimer should be arranged. For those patients that can’t access a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan within 4 hours, offer a D‑dimer test, then interim therapeutic anticoagulation and a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan with the result available within 24 hours. For those patients with a Wells score of 1 or less, arrange a D dimer test with the result available within 4 hours, or, if the D dimer test result cannot be obtained within 4 hours, offer interim therapeutic anticoagulation while awaiting the result. If the D-Dimer test is positive, arrange an ultrasound and add interim anticoagulation if not already started (see Table 5)

Table 3: Recommended workflow for suspected DVT. NICE 2023

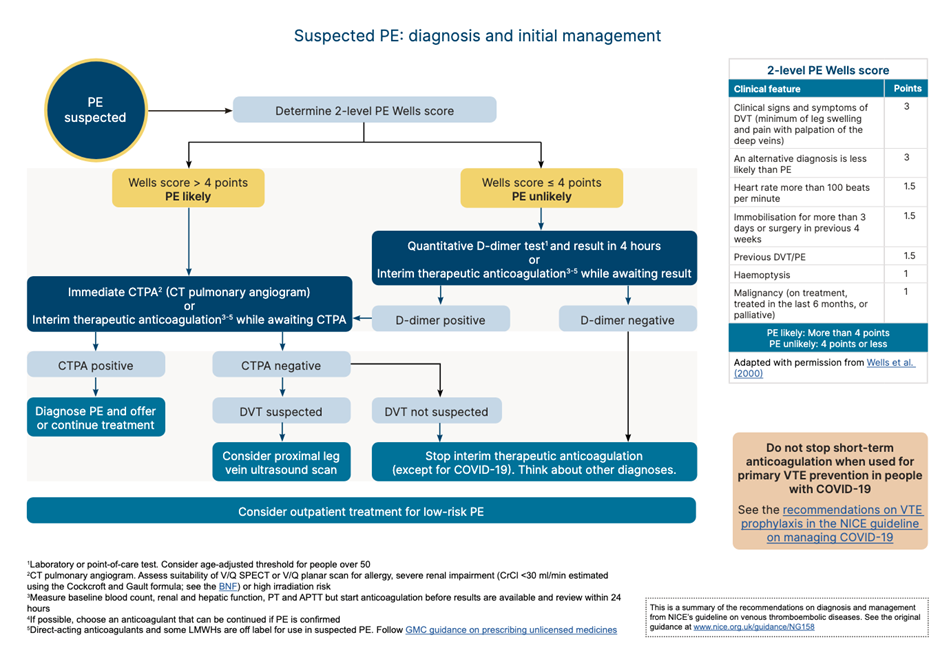

For people who present with signs or symptoms of a PE, arrange a physical examination, take a medical history and offer a chest x-ray (if available in your setting) to exclude other causes. If, after assessment and investigations, the clinical suspicion for a PE is low and other diagnoses are more likely, consider using the pulmonary embolism rule–out criteria to help determine whether any further investigations into a PE are necessary. This questionnaire has not been validated for people with COVID-19.

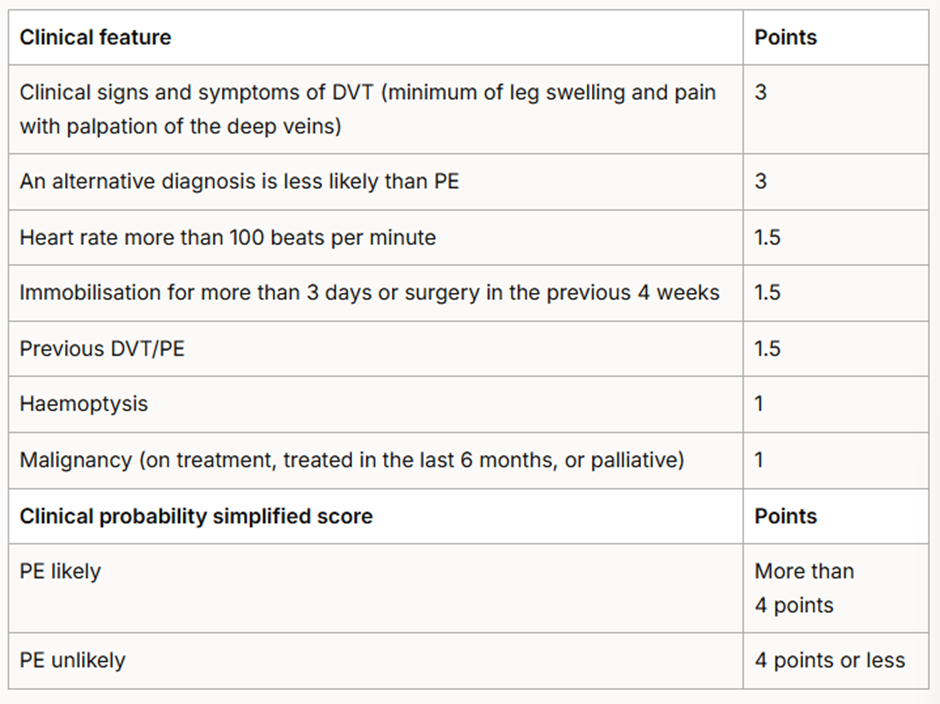

If a PE is suspected, the 2 level PE Wells score (see table 6) should be used.

If a patient scores 4 or more, NICE suggests a range of different imaging options arranged in secondary care, with anticoagulation to be initiated depending on the outcomes.

If the Wells score is 4 or less, NICE suggests D-Dimer testing with the result being available within 4 hours, or interim anticoagulation if this can’t be arranged. If the D-Dimer is positive, imaging will have to be arranged8

Table 4: Recommended workflow for PE. NICE 2023

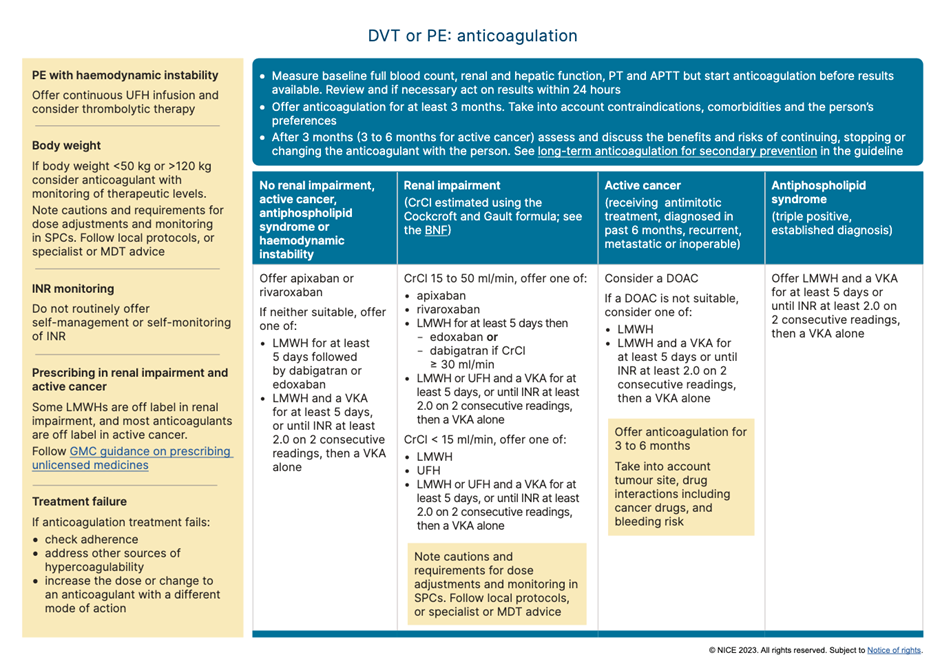

Table 5: Recommendations for anticoagulation for suspected/confirmed VTE. NICE 2023

In day-to-day practice every locality will have their own protocols and referral pathways for the management of suspected VTE in the community. Nevertheless it is important to remember that patients who score 1 or below on the DVT Wells questionnaire, should still have a D-Dimer test. This was highlighted by a case that a coroner shared with the RCGP, in which a patient tragically died four weeks after an initial assessment for calf swelling; while the Wells score was applied, the patient did not have a D-Dimer. The patient then developed respiratory symptoms and was seen by various healthcare practitioners over a 4 week period before suffering a cardiac arrest caused by a large PE.

The vast majority of patients with VTEs are being expertly managed in cooperation between primary and secondary care. General practitioners are experts in managing diagnostic uncertainty - an inevitable part of their profession - and VTE presentations can certainly can test this vital skill. Acknowledging the broad scope of symptoms and subsequent use of the local pathways for VTE can nevertheless increase the pickup rate further, improving the safety of our patients.

Table 6: Two-level PE Wells score. NICE 2023 Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing.

References

- Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, et al. Venous thromboembolism. The Lancet . 2021 Jul; 398 (10294): 64–77.

- Thrombosis UK.

- Venous thromboembolism. NHS Resolution. 2023.

- Kearon C. Natural History of Venous Thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003 Jun 17; 107 (90231): 22I-30.

- Ageno W, Haas S, Weitz JI, et al. Upper Extremity DVT versus Lower Extremity DVT: Perspectives from the GARFIELD-VTE Registry. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2019 Jun 10; 119 (08): 1365–72

- Safi M, Tajik Rostami R, Taherkhani M. Unusual presentation of a massive pulmonary embolism. J Teh Univ Heart Ctr 2011; 6( 1): 41-44.

- Walen S, Damoiseaux RA, Uil SM, et al. Diagnostic delay of pulmonary embolism in primary and secondary care: a retrospective cohort study. British Journal of General Practice. 2016 Apr 25; 66 (647): e444–50.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NG158 Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing 2023.