Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Chickenpox is a common and unpleasant childhood illness. More than 90% of the population have acquired antibodies to the causative infection (the varicella zoster virus) by the age of 151. For many it is a self-limiting illness (often leaving behind scars when scratching cannot be resisted), but there is a risk of significant complications, as listed in the box below. Those at a higher risk of complications include adults, adolescents, children aged under one, pregnant women and immunocompromised people. Around 20 people per year die of chickenpox in the UK3 and there is a risk of neonatal death if a susceptible woman contracts chickenpox in the week before delivery3.

|

Complications of chickenpox1: |

|

The economic cost to the UK of parents taking time off work to provide childcare to their children with chickenpox is estimated to be over £24 million per year4 – the difficulties of taking prolonged time off work for childcare perhaps explains why one survey (the satisfyingly named SPOTTY study5 showed that 73% of UK paediatricians surveyed had privately vaccinated their child against varicella. As the author of this blog discovered last year, chickenpox can also wreak havoc if it appears two days before a family holiday!

Until recently, NHS chickenpox vaccination has only been offered to a small group of people. These include susceptible healthcare staff (including non-clinical, e.g. cleaners, porters etc), laboratory staff who work with the varicella virus, and close household contacts of immunocompromised patients, such as siblings of a child with leukaemia, or a child whose parent is having chemotherapy3. For patients who are due to start immunocompromising medication and are susceptible to varicella, vaccination is offered if there is enough time to give the two-dose course before the medication has to be started3.

This will change in January 2026, when universal vaccination begins on the NHS in all four countries of the UK 6,7,8,9. Details of the programme are as follows10

- Offered to children at the age of 18 months.

- Given with measles, mumps and rubella as the MMRV vaccine.

- Booster at three years and four months of age.

- One-dose catch-up programme for children born between 1.1.2020 and 31.8.22, who can access the vaccine until the end of March 2028.

- No NHS offer of a single varicella vaccine.

- The MMR vaccine without varicella will no longer be available for the NHS routine childhood immunisation programme, although it will still be available for those who need the MMR vaccine in adulthood. Children who did not have MMR at the usual time and are brought later in childhood should be caught up with MMRV.

So why have the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), who decided against universal childhood varicella vaccination in 2009, changed their mind? The original decision was made on cost-effectiveness grounds, with an estimate that it would take 80-100 years for the programme to become cost-effective11. The new decision has largely been based on two factors – a review of the prevalence of chickenpox complications, and a change in the way we think about shingles in adults.

The JCVI believe that the cost of chickenpox complications has probably been underestimated, affecting their assessment of of cost-effectiveness of the vaccine. It is likely that many people admitted with complications of chickenpox have had their admission coded with the name of the complication (pneumonia, meningitis, cellulitis etc) but that the code for chickenpox was not added, so the two weren’t linked for the purposes of cost calculation11. The availability of the four-virus MMRV vaccine has also improved the cost-effectiveness calculation, as there is no need for another nurse appointment, over and above the one which would have been necessary for the MMR vaccine.

Another concern in 2009 was that vaccinating against chickenpox would put older adults at an increased risk of shingles, caused by reactivation of the varicella virus. The theory was that those who have had chickenpox in the past have their immunity regularly boosted by coming into contact with children who have varicella (which is infectious during the prodrome, before spots have appeared and children are kept at home) and that reducing chickenpox incidence in children would increase shingles in middle-aged adults. At the 2023 review it was clear that data from the United States (who have vaccinated against chickenpox since 1995) did not support this hypothesis11 – and we also now have the NHS shingles vaccination, which was not offered in 2009.

Vaccine hesitancy remains an issue in the UK, with only 85% of English 5 year olds having had two doses of MMR – uptake in some communities is significantly lower than that12. It will be interesting to see whether the addition of varicella to the MMR vaccine reduces uptake further, due to unwarranted nerves about multiple vaccine, or whether the benefits of not having to look after an irritable child with chickenpox will encourage people to vaccinate, in turn increasing MMR uptake.

References

- NICE CKS. Chickenpox. Nov 2023.

- Oxford Vaccine Group. Chickenpox (varicella). Nov 2023.

- UKHSA. Varicella: the green book, chapter 34. Sept 2024.

- LSE. The true cost of chickenpox: at least £24 million in lost productivity a year in the UK. April 2022.

- O'Mahony E, Sherman SM, Marlow R et al. UK paediatricians' attitudes towards the chicken pox vaccine: The SPOTTY study. Vaccine. 2024 Sep 17; 42 (22): 126199.

- DHSC. Free chickenpox vaccination offered for first time to children. Aug 2025.

- Department of health. Chickenpox vaccination to be offered to children in Northern Ireland from 2026. Aug 2025.

- NHS Scotland. Changes to the Scottish Childhood Vaccination Schedule from 1 January 2026 (phase 2) – introduction of a routine Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox) vaccine. Nov 2025.

- NHS Wales. New Chickenpox (Varicella) Vaccination Programme in Wales.

- UKHSA and NHSE. Introduction of a routine varicella (MMRV) vaccination programme for children at one year and at 18 months. Oct 2025.

- DHSC. JCVI statement on a childhood varicella (chickenpox) vaccination programme. Nov 2023.

- UKHSA. Evaluating the impact of national and regional measles catch-up activity on MMR vaccine coverage in England, 2023 to 2024.Aug 2024.

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

Learning disability is the preferred UK term for individuals who have a ‘significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills’ and a ‘reduced ability to cope independently which starts before adulthood with lasting effects on development’1. Mencap estimates that there are approximately 1.5 million people with a learning disability in the UK (2.16% of adults and 2.5% of children)2, but is likely that the number of diagnoses recorded in health and welfare systems is significantly lower than the actual number of people living with learning disabilities3. This group represent a widely heterogenous group of patients with a broad spectrum of diagnoses and comorbidities, and will include some without a firm diagnosis to explain their learning disabilities.

The life expectancy of people with learning disabilities is reduced compared with the general population, with only 37% of affected adults living beyond 65 years of age, compared with 85% of the general population. These patients are at disproportionately higher risk of preventable deaths; this is often due to the underlying cause of mortality not being detected early and/or a delay in appropriate referral, and sub-standard management of conditions once they have been diagnosed. A recent review of deaths of people with learning disabilities identified 42% of deaths in this group as avoidable4.

The second commonest cause of death in people with learning disabilities is respiratory (14.6%, compared with 16.7% who died of diseases of the circulatory system) with influenza and pneumonia being the most common infective causes. This clearly highlights the immense benefits this population would get from pneumococcal and influenza vaccination.

Evidence suggests that vaccine coverage rates are lower in those with a learning disability than in the general population; in children complete coverage rates were significantly lower for those with intellectual disabilities at ages nine months and three years5 and there is data to show that in the past, only half of adults receive a flu vaccination.

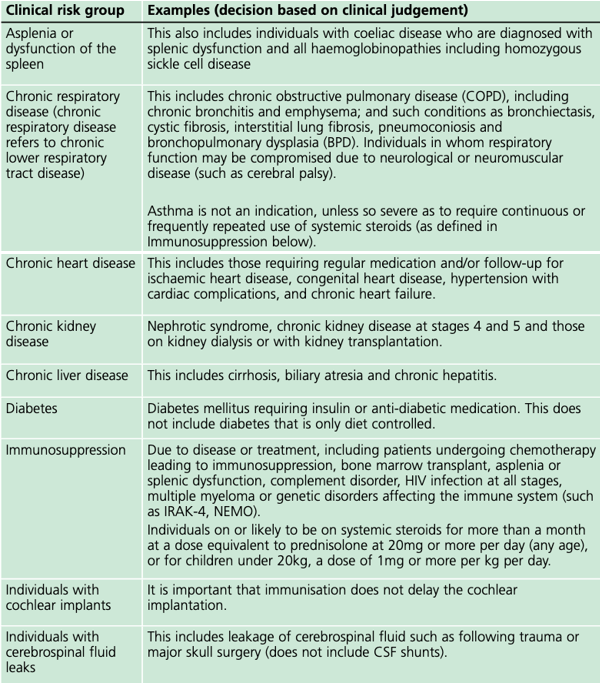

Pneumococcal vaccination is now part of the childhood vaccination regime and available for people in clinical risk groups as an additional vaccine depending on their age when they were diagnosed with a co-morbidity entitling them to the vaccination (see table).

In the risk group ‘chronic neurological disease’ (the category which includes those with learning disabilities), the mortality rate of influenza per 100,000 population is 37 times higher compared to those in no risk group. With annual influenza vaccination available for all affected since 2014, every general practice surgery has the chance to protect some of the most vulnerable people in their community, but this has not led to an appreciable increase in uptake.

To improve vaccine uptake amongst people with learning disabilities it is important to improve recording and coding (“coding is caring”!), as this will make this population more ‘visible’, facilitating invitation to annual learning disability health checks. Fear of medical interventions, including needles, may be a barrier to vaccination uptake in people with learning disabilities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NHS England developed a guide on how to increase uptake flu-vaccination for people with learning disabilities, and their key messages for GP-Surgeries were:

- GP surgeries should give a clear message that people with learning disabilities and their carers (family member and support workers) are entitled to a free flu vaccination.

- People on the learning disability register should have it recorded in their notes that they ‘need a flu vaccine’ – there is a specific Read / SNOMED code for this, or be called for vaccination using searches and reports on the clinical system.

- Practices can use this easy read flu invitation letter template for people with learning disabilities.

- Talk to people at their annual health check about why it is important that they have the flu vaccination.

- Put reasonable adjustments in place to help people with learning disabilities have their flu vaccination. This could be extra time, photo cards or an accompanying friend.

- The person seeing the patient may need to assess the patient’s capacity to decide to have the flu vaccine. If they do not have capacity for this decision, then this should not be a barrier to the flu vaccination being given; there would need to be a decision taken by the health professional that this is in their best interests.

- Consider the nasal spray flu vaccine as a reasonable adjustment. PHE guidance outlines the nasal spray can be used for people with a severe needle phobia. The nasal vaccine is not as effective as the injection, but some protection is better than none.

- Capitalise on attendance and offer the pneumococcal vaccine within the same appointment.7

In addition, people might benefit from scheduling their annual review during flu-vaccination season to try to immunise them opportunistically. The guide ‘Flu vaccinations: supporting people with learning disabilities’ from the UKHSA has a collection of resources on how to improve vaccine coverage for the target population.

Utilising these suggestions will increase vaccine coverage and improve health outcomes for one of the most vulnerable groups we look after in primary care.

References:

- Department of Health. Valuing People; A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century. 2001.

- Mencap. How common is learning disability in the UK?

- NHS England and NHS Improvement. Improving identification of people with a learning disability: guidance for general practice. 2019.

- LeDeR Autism and learning disability partnership, King's College London. Learning from Lives and Deaths - People with a learning disability and autistic people (LeDeR) report for 2022. 2023.

- Emerson E, Robertson J, Baines S, Hatton C. Vaccine Coverage among Children with and without Intellectual Disabilities in the UK: Cross Sectional Study. BMC Public Health. 2019 Jun 13; 19 (1).

- UK Health Security Agency. Pneumococcal: the green book, chapter 25

- Learning Disability & Autism Programme Team – NHS England & Improvement, South West. Communications toolkit: Increasing uptake of the flu vaccination for people with learning disabilities. 2020.