Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Introduction

Constipation is a common, frequently encountered gastrointestinal disorder affecting approximately one third of adults 60 years and older, with over half of nursing home residents affected. Constipation can have significant consequences: in susceptible and frail older people, excessive straining can trigger a syncopal episode and coronary or cerebral ischaemia. In severe cases, constipation can lead to anorexia, nausea and pain and ultimately can cause a stercoral ulcer, leading to perforation and death. Stercoral ulcers are due to hard, impacted faeces causing pressure necrosis of the distal colon, leading to ulceration and subsequent perforation of the intestinal wall.

Constipation often causes a reduction in the quality of life, with general health, vitality, social functioning and mental health all affected. Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age, inactivity, low calorie intake, a low-fibre diet, polypharmacy, and low income. The incidence of constipation is three times higher in women, and women are twice as likely as men to see their primary care team for constipation.

Symptoms

Patients usually complain of ‘straining’ when opening their bowels, difficulty passing stools, incomplete evacuation or both. This is often associated with hard stools, abdominal bloating pain and distention. The stool frequency may be normal.

Primary constipation

Primary constipation includes the subtypes of normal transit, slow transit and disorders of defaecation, all of unknown causes. Histology of the colon of older adults shows more tightly packed collagen fibres and a reduced number of myenteric neurons, but these changes are not considered to be major contributors to the development of constipation.

Secondary constipation

Secondary causes of constipation include medication use, chronic disease processes and psychosocial issues. Opioids, calcium channel blockers, oral iron supplements, antacids and anticholinergics are common causes for medication-induced constipation, while hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, Parkinson’s disease and colorectal carcinoma can all cause secondary constipation.

Assessment

Patients should always be assessed for red flags that might indicate an underlying malignancy, such as:

· persistent unexplained change in bowel habits

· palpable mass in the lower right abdomen or the pelvis

· persistent rectal bleeding without anal symptoms

· narrowing of stool calibre

· family history of colon cancer, or inflammatory bowel disease

· unexplained weight loss, iron deficiency anaemia, fever, or nocturnal symptoms

· severe, persistent constipation that is unresponsive to treatment.

NICE guidance NG12 gives primary care practitioners a clear framework when to refer a patient with suspected colorectal cancer on a two week wait (2ww) suspected cancer pathway referral.

When evaluating an older individual with constipation, taking a thorough drug and medical history and performing a physical examination are important. Abdominal examination might reveal abnormal bowel sounds, significant weight loss, cachexia, masses and/or sigmoid or colonic loading. When planning a rectal examination, the patient should be informed about its diagnostic importance and the fact that it might be uncomfortable. A chaperone should always be offered and consent documented. Examination of the anus might reveal abnormalities such as proctitis, haemorrhoids, prolapse, fissures or rectal cancer, while further up in the ampulla a rectal-digital examination can detect faecal impaction, masses, and gives the examiner the chance to evaluate anal tone.

Management

Non-pharmacological treatment is often the first step to help patients in the management of their complaint with adaptation of the patients’ medication a start to reduce symptoms.

Endocrinological/psychological/neurological causes of secondary constipation will need investigation and appropriate management. It might be worth discussing with the patient that there is no physiological necessity to have a daily bowel motion: a discussion around simple lifestyle changes might improve their perception of bowel regularity and a diary reporting on stool pattern and consistency may be helpful as well. The optimal time to have a bowel movement is often after waking and/or after meals, when the colon’s motor activity is particularly pronounced. A gradual increase in the intake of fluids and fibre should be suggested, but we should be careful in patients with cardiorenal issues not to cause overloading. A prospective study from Japan found that placing the patient’s feet on a small foot stool in front of the toilet, in conjunction with the upper body bent forward, improved anal pressure and reduced time of evacuation. Patients in care homes should be given adequate time and privacy for their bowel movements and should avoid bed pans.

Most patients will, at one stage, require a laxative to alleviate their symptoms when lifestyle interventions are ineffective: in patients with short-duration constipation a bulk forming laxative such as ispaghula husk should be initiated. If these are not helpful, an osmotic laxative such as macrogol should be next.

In chronic constipation, a bulk forming laxative should be initiated, with adequate hydration ensured (low fluid intake with bulk forming laxatives can cause impaction). If defaecation continues to be unsatisfactory, an osmotic laxative should be the next choice, with the addition of a stimulant laxative such as bisacodyl if the patient doesn’t improve. Once regular bowel movements occur, the laxatives can be slowly withdrawn.

If there is no response to the maximum tolerated dose of second line laxatives, refer to the local GI or older people’s outpatient team, or ask for guidance via the local advice and guidance process.

If the patient presents with faecal impaction, the appropriate escalating dose of a macrogol should be considered. In those with soft stools, or with hard stools after a few days’ treatment with a macrogol, an oral stimulant laxative should be started or added to the previous treatment. If the response continues to be underwhelming, rectal administration of bisacodyl (for soft stools) or glycerol (for hard stools) can be considered.

If there is still no response, a sodium acid phosphate with sodium phosphate enema may have to be considered. For hard stools, an overnight arachis oil enema, followed by a sodium acid phosphate with sodium phosphate enema the next morning might prove effective.

In patients with opioid-induced constipation, an osmotic laxative (or docusate sodium to soften the stools) and a stimulant laxative is recommended. Bulk-forming laxatives should be avoided.

If the patient’s presentation is getting worse or there is no response, then consult with one of your colleagues from gastroenterology. Further input from these teams might be needed for additional pharmacotherapy, endoscopy, anorectal manometry or other secondary/tertiary care investigations.

References:

Arco, S; Saldaña, E et al (2021). Functional Constipation in Older Adults: Prevalence, Clinical Symptoms and Subtypes, Association with Frailty, and Impact on Quality of Life. Gerontology DOI: 10.1159/000517212

British National Formulary: Constipation https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/constipation/ accessed 14/7/2022

Gandell, D; Straus, SE et al (2013). Treatment of constipation in older people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, May 14, 185(8) DOI:10.1503/cmaj.120819

De Giorgio, R; Ruggeri, E et al (2015). Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterology 15:130 DOI 10.1186/s12876-015-0366-3

Gough, AE; Donovan, MN et al (2016). Perforated Stercoral Ulcer: A 10-year experience. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Vol 64, No 4

Heidelbaugh, J; Martinez de Andino, N et al (2021). Diagnosing Constipation Spectrum Disorders in a Primary Care Setting. Journal of Clinical Medicine. (10) 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10051092

Hull and East Riding Prescribing Committee (2019). Management of Constipation in Adults. https://www.hey.nhs.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/GUIDELINE-Constipation-guidelines-updated-may-19.pdf accessed 14/7/2022

Jamshed, N; Lee, Z; Olden, KW (2011). Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults. American Family Physician. 84(3):299-306

Mounsey, A; Raleigh, M et al (2015). Management of Constipation in Older Adults. American Family Physician Volume 92, Number 6

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021). NG12 Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/chapter/Recommendations-organised-by-site-of-cancer#lower-gastrointestinal-tract-cancers accessed 14/7/2022

Rome Foundation (2016) Appendix A: Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for FGIDs. https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/ accessed 14/7/2022

Schuster, BG; Kosar, L et al (2015). Constipation in older adults; Stepwise approach to keep things moving. Canadian Family Physician 61: February

Takano, S; Nakashma, M et al (2018). Influence of foot stool on defecation: a prospective study. Pelviperineology 2018; 37: 101-103

Villanueva Herrero JA, Abdussalam, A et al (2022). Rectal Exam. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30726041/

The majority of people, including health care professionals (HCPs), have unconscious or implicit biases1. These can affect the way we interact with colleagues, staff and patients, and even influence our decision making in regards to diagnosis and management of conditions2.

Unconscious bias is the immediate judgement of something, or someone, based on our past experience, background and culture. It is instinctive rather than a rational thought process and occurs almost instantaneously on encountering someone new. This bias can then influence our thoughts, beliefs and behaviour towards that person.

When we first meet someone, we subconsciously categorise them based on, for example, their gender, age, skin colour, accent, profession, sexual orientation3. We then use preconceived ideas of their intrinsic characteristics and form an immediate opinion about the person. Most people have unconscious biases, no matter how strongly they consciously oppose discrimination or prejudice. We tend to feel positively about someone who is similar to us, and negatively about those we perceive as ‘different’. These assumptions then effect the relationship we have with that person, including how close we will stand to them, and how often we make eye contact2.

The term unconscious bias encompasses several types of bias such as gender bias, confirmation bias, age bias, and affinity bias, to name a few. These biases can affect everything from to which candidate we would offer a practice vacancy, to how we manage different patients with the same condition. It can be both positive and negative, as we may favour or disapprove of someone based on whether we feel they fit into ‘our group’ (namely, whether we feel they share similar characteristics to us).

Take a vacant salaried GP position as an example: You’re on the interview panel. The next applicant trained at the same medical school and enjoys the same hobbies as you. You immediately think ‘yes, this person is great’. The next applicant attended a rival medical school and has different hobbies; you’re not so sure about this applicant. This is an example of affinity bias. These opinions are formed without us even realising it and without taking into account the person’s qualifications or experience. Once that initial judgement is formed, our brain then begins to gather evidence to support our assessment. However, this ‘evidence’ is also biased (confirmation bias) as we look for anything that will uphold our initial decision and disregard items that refute it.

Unconscious bias is well recognised in the interviewing process, and many private companies have procedures in place to reduce the risk of this happening4. But how does this translate into the world of healthcare?

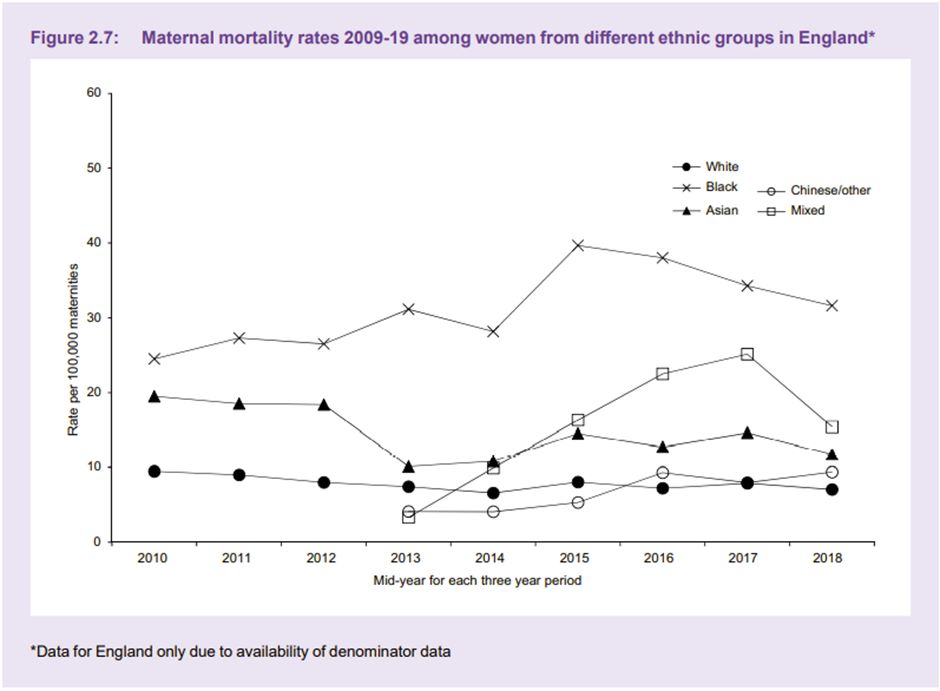

Unconscious bias may have a significant impact on medical school admissions, with one American study reporting a notable race bias5 by those on the selection panel. International medical graduates (IMGs) are up to thirteen times more likely to be referred to the GMC than UK graduates6, which is thought to be due, at least in part, to unconscious bias. We commonly hear of female doctors being called nurse whilst male nurses or medical students are called doctor and are often talked to in preference to their senior female colleague.Not only does unconscious bias affect us and our colleagues, but it also has a crucial and concerning impact on our patients. In 2021 Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risks through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK (MBRRACE-UK) released a report7 that showed black women were four times more likely to die in pregnancy than white women. Whilst socioeconomic factors and medical reasons were thought to contribute to the outcomes, this only accounted for a small proportion of women. Black women report not being listened to or empathised with as much as their white counterparts8.

Graph from MMBRACE-UK 'Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19'. Used with permission from MMBRACE-UK.

Several studies have shown that there is racial bias in regards to pain management, with black people frequently denied analgesia that their white counterparts are readily offered. Research by Hoffman et al (2016) reported that the false belief of biological differences between white and black people contributing to pain thresholds, are held by the general population, and more worryingly by medical students and qualified doctors9. This not only impacts women in labour, but all situations where adequate pain relief is important.

The Midlands Leadership Academy has developed an Unconscious Bias Toolkit10 which suggests several ways in which we can challenge our own unconscious biases. The toolkit advises us to consider:

- What am I thinking?

- Why am I thinking it?

- Is there a past experience that is impacting my current decision?

- Is the past experience applicable now or is it based on a preference or bias?

Furthermore, the Royal Society4 advise that we should slow down when making decisions, reconsider reasons for decisions, question cultural stereotypes and monitor each other for unconscious bias. The Royal College of Surgeons have published a document on reducing unconscious bias11 in which they suggest using Thiederman’s Seven Steps for defeating bias in the workplace.

|

1. Become mindful of your biases 2. Put your biases through triage 3. Identify the secondary gains of your biases 4. Dissect your biases 5. Identify common kinship groups 6. Shove your biases aside 7. Fake it till you make it (what we say can become what we believe) |

Medical education - whether undergraduate or postgraduate - has a responsibility to promote curricula in a non-biased way. There has recently been a push to decolonise medical education and incorporate cultural safety12: Decolonising medical education involves challenging beliefs and introducing ‘new normals’ such as representing signs and symptoms of illnesses in different skin tones; or promoting issues faced by discriminated groups, for example, including violence against women and racism in curricula13. Cultural safety is a concept developed by Māori Nurse Educator Irihapeti Merenia Ramsden, who recognised the health inequalities between indigenous and non-indigenous people in New Zealand. Cultural safety is to understand that health inequality is based on historical prejudice, and using lived experiences of those who have experienced discrimination ensures that differences in culture are respected throughout healthcare. If health care professionals and students understand how conditions may present in different ethnicities and genders, really listen to patients experiences and concerns regardless of their skin colour or own beliefs, and learn to challenge their unconscious bias, then hopefully we will develop a generation of healthcare professionals who can more fully appreciate and challenge health inequality in the UK.

The RCGP has recently launched an interactive eLearning module on Allyship, which includes information and suggested actions to promote anti-racism and bystander intervention. You can access the course here: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/allyship

References

- Schwarz, J., 1998. Roots of unconscious prejudice affect 90 to 95 percent of people, psychologists demonstrate at press conference, University of Washington, [online]. Available at: https://www.washington.edu/news/1998/09/29/roots-of-unconscious-prejudice-affect-90-to-95-percent-of-people-psychologists-demonstrate-at-press-conference/ [Accessed 06 April 2022]

- FitzGerald, C. and Hurst, S., 2017. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8.

- Rice, M., 2015. Unconscious bias and its effect on healthcare leadership. Healthcare Network, The Guardian. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2015/may/19/healthcare-leadership-best-practice-unconscious-bias. [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Frith, U., 2015. Understanding Unconscious Bias. The Royal Society. [online] Available at: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2015/unconscious-bias/?gclid=CjwKCAiA6seQBhAfEiwAvPqu18TssncdweUmNPHBiUb8o2UHBslILV8UOvM-fs7ePvbngXtmq6fdrRoC-PYQAvD_BwE. [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Capers, Q., 4th, Clinchot, D., McDougle, L., and Greenwald, A. G., 2017. Implicit Racial Bias in Medical School Admissions. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92(3) pp.365–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

- Rimmer A, 2017. Unconscious bias must be tackled to reduce worry about overseas trained doctors, says BAPIO. British Medical Journal, 357 :j1881 doi:10.1136/bmj.j1881.

- Knight, M., et al on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19. [online] Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2021. Available at: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2021/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2021_-_FINAL_-_WEB_VERSION.pdf [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Brathwaite, C., 2018. Black Mothers Are Disproportionately More Likely To Die In Childbirth - We Need To Address The Race Gap In Motherhood. Huffington Post [online] Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/race-motherhood-black-mothers-dying-childbirth_uk_5c078da3e4b0a6e4ebd9d5ec [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Hoffman, K.M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J.R., and Oliver, M.N., 2016. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), pp.4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.

- Masuwa, P. and Sharma, M. Unconscious bias toolkit. NHS Midlands Leadership Academy. [online] Available at: https://midlands.leadershipacademy.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/12/Unconscious-bias-toolkit-final-version.pdf.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2016. Avoiding Unconscious Bias: A guide for surgeons. [online] London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England (Published 2016) Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/rcs-publications/docs/avoiding-unconscious-bias/ [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Wong, S.H.M., Gishen, F. and Lokugamage, A.U., 2021. ‘Decolonising the Medical Curriculum‘: Humanising medicine through epistemic pluralism, cultural safety and critical consciousness. London Review of Education, 19(1). DOI: 10.14324/LRE.19.1.16.

- Lokugamage, A.U., Ahillan, T. and Pathberiya, S.D.C., 2020. Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics 46(4), pp.265-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866.