Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Pneumonia is defined as an infection of the lung tissue, in which the alveoli become filled with micro-organisms, fluid and inflammatory cells, affecting the function of the lungs1. Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) has a mortality rate of around 1% in those who are managed in primary care, rising to up to 14% for those admitted to hospital and to 30% for those who need intensive care1. GPs need to risk stratify and make logical decisions as to who can be managed in the community, and who needs referral and consideration of admission.

An experienced GP will be used to assessing severity of acute infection. We make a clinical assessment, starting with an overall look at the patient (do they look unwell or otherwise make our antennae twitch?), assessment of vital signs such as pulse, respiratory rate, temperature and oxygen saturations, and consideration of co-morbidities such as immunosuppression. The NICE guidance on pneumonia2, published in September 2025, recommends the more formal CRB65 tool, once we have made a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia.

Technology is available to measure C-reactive protein (CRP) as a point of care test in primary care, to help support or refute a diagnosis of inflammation, as occurs in an infection such as pneumonia. A 2016 NICE MedTech innovation briefing3 noted that primary care CRP testing can reduce antibiotic prescribing and referrals for chest x-ray, but that the sensitivity did not rise above 55% (and could be as low as 20% depending on the threshold used). Specificity was better, ranging from 73 – 99%. In the nine years since that briefing, the test has not become widely available, with barriers including cost, lack of commissioning enthusiasm and concern about the evidence base for effectiveness and value for money. A 2025 qualitative review4 comparing the UK with Sweden, the Netherlands and Canada, found that uptake of primary care CRP testing was higher in the other countries, but that clinicians didn’t feel that it had made a huge improvement to their assessment of patients with possible pneumonia, with some saying that the introduction was a policy failure, and the test over-used. Other studies have shown that CRP use is associated with increased antibiotic prescribing, rather than helping to reassure that antibiotics aren’t needed, and that this is particularly associated with systems where a CRP is checked before the patient is seen, resulting potentially in spurious high results in those with a low pre-test probability of bacterial infection5. NICE does not discuss primary care CRP in its latest guideline2, but where it is being used the Primary Care Respiratory Society suggests cut-offs of 20 and 40 mg/L – do not prescribe antibiotics with CRP<20, consider prescribing with CRP of 20-40 if there is purulent sputum, and prescribe with CRP>406.

The CRB65 scoring system is outlined in the box below and the results predict the risk of death in the next 30 days. Zero is low risk (<1%), 1 or 2 intermediate risk (1 – 10%) and 3 or 4 high risk (>10%).

CRB65 score – one point for each of the following:

- Confusion (new disorientation in person, place or time, or a score of ≤8 on an abbreviated mental test).

- Respiratory rate ≥30.

- Blood pressure ≤60 mmHg diastolic or 90 mmHg systolic.

- Age ≥65.

NICE write ‘guidelines not tramlines’7, and this guideline acknowledges the holistic nature of our assessment, advising the use of clinical judgment along with the CRB65 score, which can be affected by other factors such as comorbidities or pregnancy. NICE advises considering referral with a CRB65 score ≥2, and that those with a CRB65 score of 1 might benefit from an assessment in a same-day emergency care unit (which is in any case often where those referred to hospital will end up) or by being referred to a virtual ward or hospital at home service. Those with a score of zero can be managed in primary care, with appropriate safety-netting to return if symptoms deteriorate. Any signs of significant complications, such as heart failure, would lower the threshold for referral. We should have a lower threshold for children and young people (those aged under 18), considering referral or specialist advice for every patient.

For those not admitted, we would usually treat pneumonia with antibiotics in the community, to be started as soon as possible after the clinical diagnosis has been made2. Whilst some causes are viral, the majority of pneumonia has a bacterial cause1, and we cannot reliably differentiate between the two. The commonest bacterial cause is Streptococcus pneumoniae, with other responsible organisms including Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and the atypical Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Those who are immunocompromised, or who have had multiple recent courses of antibiotics, may be more likely to have an unusual or drug-resistant bacteria (or a fungal infection such as Aspergillus) as a cause for their pneumonia8,9; pneumonia in those with an unsafe swallow may be related to aspiration of stomach contents10.

NICE emphasises the need for only a five day course of antibiotics for adults and three days for children aged up to 11, with a longer duration only when clinically necessary. This may be because they have had a temperature in the last 48 hours of the five day course, or that they continue to have a sign of clinical instability, such as (in adults) systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, heart rate >100 bpm, respiratory rate >24 breaths per minute or oxygen saturations <90% on air. These parameters, if present after five days of antibiotics, might make us re-visit the decision to keep the patient at home. The suggested first-line antibiotic for low-severity disease is amoxicillin, with doxycycline or clarithromycin as second-line, and erythromycin for pregnant women. For moderate severity disease the choice is largely the same, although clarithromycin moves to first line if an atypical bacterial cause is suspected. Those with high-severity disease are likely to be in hospital, but if treated in the community then a combination of co-amoxiclav and clarithromycin are first line, with erythromycin in pregnancy and levofloxacin as an alternative for those with penicillin allergy (bearing in mind the MHRA advice on quinolones11).

Distinguishing between typical and atypical bacterial causes without a sputum sample is by no means an exact science; those with an atypical bacteria may have more prolonged or prominent constitutional symptoms (headache, malaise, sore throat, fever) and may be less likely to have clear consolidation on auscultation of the chest. Atypical infection can come in epidemics, with many cases clustered together and then none for several years and is more common with increasing age and in those who live in enclosed spaces such as boarding schools or military barracks. Outbreaks of one particular atypical bacteria, Legionella pneumophila are associated with contaminated water and air-conditioning systems and another, Legionalla longbeachae is associated with exposure to contaminated soil mixtures12. Consideration of an atypical bacteria should be given when the patient doesn’t respond to an apparently appropriate first-line choice of antibiotic, and where there is a history of staying in a hotel or resort where exposure may be more likely.

Further reading and useful resources

- RCGP eLearning modules on Aspergillus and pneumonia.

- NICE guidance on pneumonia.

- StatPearls articles on aspiration pneumonia, atypical pneumonia and pneumonia in the immunocompromised patient.

- Patient information leaflet and NHS webpage on pneumonia.

References

- NICE CKS. Chest infections – adult. Jan 2025.

- NICE. NG250. Pneumonia: diagnosis and management. Sept 2025.

- NICE. MIB81. Alere Afinion CRP for C-reactive protein testing in primary care. Sept 2016.

- Glover RE, Pacho A, Mays N. C-reactive protein diagnostic test uptake in primary care: a qualitative study of the UK's 2019-2024 AMR National Action Plan and lessons learnt from Sweden, the Netherlands and British Columbia. BMJ Open. 2025 Aug 31;15(8):e095059.

- Payne R, Mills S, Wilkinson C et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing in general practice out-of-hours services: tool or trap? Br J Gen Pract. 2025 Aug 28;75(758):388-389.

- Primary Care Respiratory Society. The place of point of care testing for C-reactive protein in the community care of respiratory tract infections. Summer 2022.

- Reeve J. Avoiding harm: Tackling problematic polypharmacy through strengthening expert generalist practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Jan;87(1):76-83.

- Aleem MS, Sexton R, Akella J. Pneumonia in an Immunocompromised Patient. [Updated 2023 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Assefa M. Multi-drug resistant gram-negative bacterial pneumonia: etiology, risk factors, and drug resistance patterns. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2022 May 5;14(1):4.

- Sanivarapu RR, Vaqar S, Gibson J. Aspiration Pneumonia. [Updated 2024 Mar 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- MHRA. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: must now only be prescribed when other commonly recommended antibiotics are inappropriate. Jan 2024.

- Nguyen AD, Stamm DR, Stankewicz HA. Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia. [Updated 2025 Apr 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

Written by Dr Emma Nash

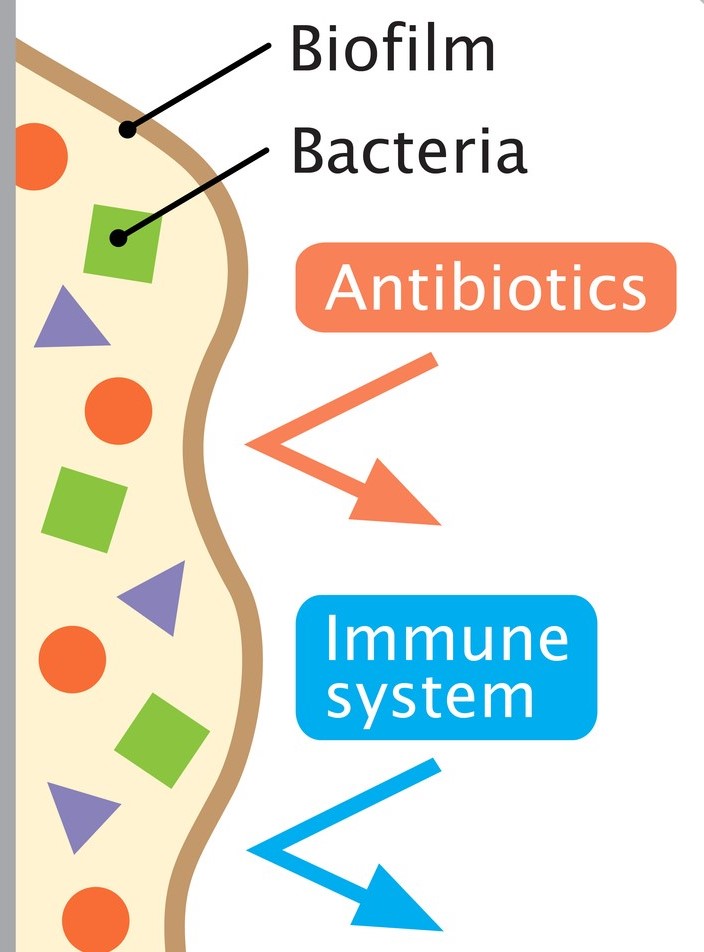

Cough is one of the most frequent reasons for presentation to primary care, particularly in children. Acute cough is most commonly caused by upper respiratory tract infections; chronic cough (over four weeks) is typically attributed to recurrent respiratory tract infection, asthma or pertussis. However, a wet cough lasting more than four weeks should prompt consideration of protracted bacterial bronchitis, also known as persistent bacterial bronchitis (PBB). First described in a study in 2006, the condition is being increasingly recognised clinically. However, there is no clarity on the underlying mechanisms, making definitive diagnostic and therapeutic guidance elusive. Proposed pathophysiological contributory factors include impaired mucociliary clearance, systemic immune function defects (raised NK-cell levels, altered expression of neutrophil-related mediators), and airway anomalies (tracheobronchomalacia). It is also thought that bacteria may produce a biofilm in the airways. This is a secreted matrix that enhances bacterial attachment to cells and facilitates access to nutrients. It also decreases antibiotic penetration, thus protecting the bacteria and making them harder to eradicate with standard length courses of treatment.

PBB is initially difficult to distinguish from a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The cough is productive, but the child is systemically well. Although wheeze is variably reported, the evidence is that there is a limited response to bronchodilator therapy, if any. Chest examination is typically normal, but if a wheeze is heard, it is monophonic rather than the polyphonic wheeze found in asthma. Sinus and ear disease is absent.

PBB is a clinical diagnosis. It may be suspected when the first two of the European Respiratory Society criteria are met, and confirmed when all three are met:

1. Presence of continuous chronic wet or productive cough (>four weeks’ duration).

2. Absence of symptoms or signs suggestive of other causes of wet or productive cough (see box 1).

3. Cough resolved following a two-to-four-week course of an appropriate oral antibiotic.

|

Box 1:

Pointers suggestive of causes other than PBB.

|

The median age of development is 10 months – 4.8 years and it affects more males than females. PBB is no more common in children with an atopic history, but one study has shown that children who attend childcare are significantly more likely to develop PBB than those who do not. Children with an airway malacia are at increased risk of developing the condition as it is harder to clear mucus when the airways tend to collapse. If this is an underlying factor for a particular child, giving a bronchodilator may exacerbate the symptoms as the airways relax even further. PBB is frequently misdiagnosed, or inadequately treated, resulting in a persistence of symptoms and potential structural damage in the form of bronchiectasis.

Most children who have PBB are not able to expectorate sputum for culture due to their age, so treatment is based on the sensitivity profiles of the typical pathogens. Haemophilus influenzae is the most common causative organism, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. However, sputum culture should be sent, if feasible.

Previously, antibiotic treatment courses have been longer, and there has been much debate over optimal drug choice and duration. More recent evidence has shown that two weeks may be adequate in many cases. A further two weeks should be prescribed if the child has improved significantly but is not completely cough free. A minority will need longer courses, but if this is the case, there should be a high index of suspicion for more severe disease such as chronic suppurative lung disease (e.g. cystic fibrosis) or bronchiectasis. Therefore, failure of the cough to respond to four weeks of antibiotics should prompt discussion with a paediatrician for consideration of next steps and whether investigation is needed for underlying causes. A reasonable pathway in primary care would therefore be that a GP suspects PBB because the first two criteria are met, treats with two weeks of antibiotics (and a further two if there is no improvement) and then seek specialist advice if the cough persists after four weeks of antibiotics. Chest x-ray is generally only needed if there is a specific reason, such as focal chest signs of concern.

Previously, antibiotic treatment courses have been longer, and there has been much debate over optimal drug choice and duration. More recent evidence has shown that two weeks may be adequate in many cases. A further two weeks should be prescribed if the child has improved significantly but is not completely cough free. A minority will need longer courses, but if this is the case, there should be a high index of suspicion for more severe disease such as chronic suppurative lung disease (e.g. cystic fibrosis) or bronchiectasis. Therefore, failure of the cough to respond to four weeks of antibiotics should prompt discussion with a paediatrician for consideration of next steps and whether investigation is needed for underlying causes. A reasonable pathway in primary care would therefore be that a GP suspects PBB because the first two criteria are met, treats with two weeks of antibiotics (and a further two if there is no improvement) and then seek specialist advice if the cough persists after four weeks of antibiotics. Chest x-ray is generally only needed if there is a specific reason, such as focal chest signs of concern.

Unfortunately, no nationally accepted guidelines exist on treatment choice. The most commonly used antibiotic is oral co-amoxiclav but alternatives such as oral second or third generation cephalosporins, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a macrolide may be used when there is a history of an IgE-mediated reaction to penicillin.

It is worth noting that recurrent episodes are common, occurring in up to 76% of cases. Antibiotic prophylaxis may be helpful in children who have more than three recurrences in twelve months. Common choices for prophylaxis are azithromycin three days a week, or co-trimoxazole daily, but this would be on specialist advice.

References

American Thoracic Society. Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis (PBB) in Children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 198, P11-P12. View patient education sheet on Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis (PBB) in Children. [accessed 20 March 2024]

Bergmann M, Haasenritter J, Beidatsch D, et al. Coughing children in family practice and primary care: a systematic review of prevalence, aetiology and prognosis. BMC Pediatr. 2021 Jun 4;21(1):260.

Di Filippo P, Scaparrotta A, Petrosino Mi et al. An underestimated cause of chronic cough: The Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis. Ann Thorac Med. 2018 Jan-Mar;13(1):7-13.

Kansra S. Diagnosis and Management of Children with Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis PBB. Sheffield Children’s Hospital NHS Trust. 2017. Download guideline on Diagnosis and Management of Children with Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis PBB. [accessed 20 March 2024]

Kantar A, Chang A, Shields MD, et al. ERS statement on protracted bacterial bronchitis in children. European Respiratory Journal 2017 Aug; 50(2):1602139.