Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

An ectopic pregnancy is one in which the fertilised egg implants outside of the uterus; around 95% are in a fallopian tube, but an ectopic can also occur on the ovary, elsewhere in the pelvis, and sometimes in the cervix or in a caesarean section scar. Around 1% of all pregnancies are ectopic, with this figure at least doubling for pregnancies arising from in-vitro fertilisation (IVF)1,2. Non-tubal ectopic pregnancies are associated with higher morbidity and mortality than tubal ectopics, often presenting late with a sudden onset of symptoms prior to rupture, collapse and death.

Bleeding from an ectopic pregnancy can be fatal and the numbers of deaths in the UK and Ireland increased between the 2018-20 and 2020-22 reporting periods (8 deaths in 2018-20 and 12 in 2022-22)3,4, with the 2024 MBRRACE-UK report noting that there were learning points for both primary and secondary care and that improvements to care may have made a difference for nine out of the 12 women who died. None were judged to have received good care, with three cases where improvements would probably not have affected the outcome. Many of these were around the presentation of women who did not know that they were pregnant; the rest of this blog will focus on the lessons for general practice. Those wanting more information on lessons for secondary care or the ambulance service can find them in the 2024 MBRRACE-UK report4.

Always consider the possibility of pregnancy

Unless there is a clear history of a total hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy, always consider pregnancy in a woman of reproductive age. Women who have irregular periods, or who have bled at the time of implantation, may not realise that they have missed a period; those who are pregnant as a result of failed contraception might not consider it as a possibility. Pregnancies due to a failure of sterilisation or intrauterine contraception in particular are at higher risk for being ectopic.

Symptoms may be atypical

When presented with a woman who has pelvic pain and/or vaginal bleeding, with a delayed period, most of us would consider an ectopic pregnancy. This may not be the case if the presentation is more subtle. Symptoms can include breast tenderness, diarrhoea or vomiting, dizziness, shoulder tip pain and rectal pressure, and some women will collapse with no previous symptoms and no knowledge that they are pregnant1,4. NICE gives the following advice: “During clinical assessment of women of reproductive age, be aware that they may be pregnant, and think about offering a pregnancy test even when symptoms are non-specific”5. If a home pregnancy test was done, consider whether it may have been done too early, such that a false negative result was obtained.

Do you know where pregnancy tests are kept at work?

General practice is not resourced to offer routine testing for confirmation of pregnancy, and this has in some cases led to tests being unavailable or locked away. It is important that all practices hold some easily accessible pregnancy tests so that they can be used when there is a clinical reason to do so. Women may not have done a test at home because they didn’t think pregnancy was a possibility, or because of issues with access or affordability; adolescents in particular are less likely to confirm pregnancy promptly with a test6.

There are issues with access to early pregnancy assessment units (EPAUs)

The MBRRACE-UK report4 described calls not returned, issues with language barriers, and waits of over 24 hours for an appointment. Clearly any woman who is haemodynamically unstable at presentation should be referred via the emergency department, rather than via EPAU, but a woman who is stable when seen by her GP, may not remain so over the course of a long wait for an EPAU appointment. Commissioning GPs reading this blog might want to reflect on EPAU access in their area; are women reliably seen within 24 hours, seven days a week, and does the service have access to enough people to answer the phone, and interpretation available in person and on the phone? As GPs, we should not be reticent in saying if we feel that a service for an individual patient isn’t good enough, and if an EPAU appointment isn’t offered in a reasonable timeframe then referral to the on-call gynaecology team may be appropriate.

Health inequalities matter

Vulnerable women are over-represented among those who died from an ectopic in 2020-2022, with one-sixth having language difficulties and nearly half having either a mental health diagnosis or issues with substance use or domestic abuse. These inequalities may prevent women’s concerns from being heard; practices should consider how the care of women who may find it more difficult to get their message across can be optimised, even in the difficult, time-pressured situation of the current NHS. The RCGP’s Health Inequalities Hub has more resources in this area.

How do you manage a pregnant woman with a past ectopic, or who is at a high risk for ectopic pregnancy?

Almost one in five women who has had an ectopic pregnancy will have another one1; this is largely unaffected by the mode of treatment for the original ectopic. Aftercare of a woman who has had an ectopic should include the fact that she needs a scan at around 6-7 weeks of gestation in any subsequent pregnancies, to ensure that the pregnancy is intrauterine1. Depending on local pathways, this may need to be arranged by the GP, or the woman may be given open access to EPAU to arrange this. An early scan should also be arranged if there is a history of damage to the fallopian tubes (including in pregnancy after failed or reversed sterilisation7), and in women who become pregnant with an intrauterine device in place; up to 50% of such pregnancies may be ectopic.

Further information

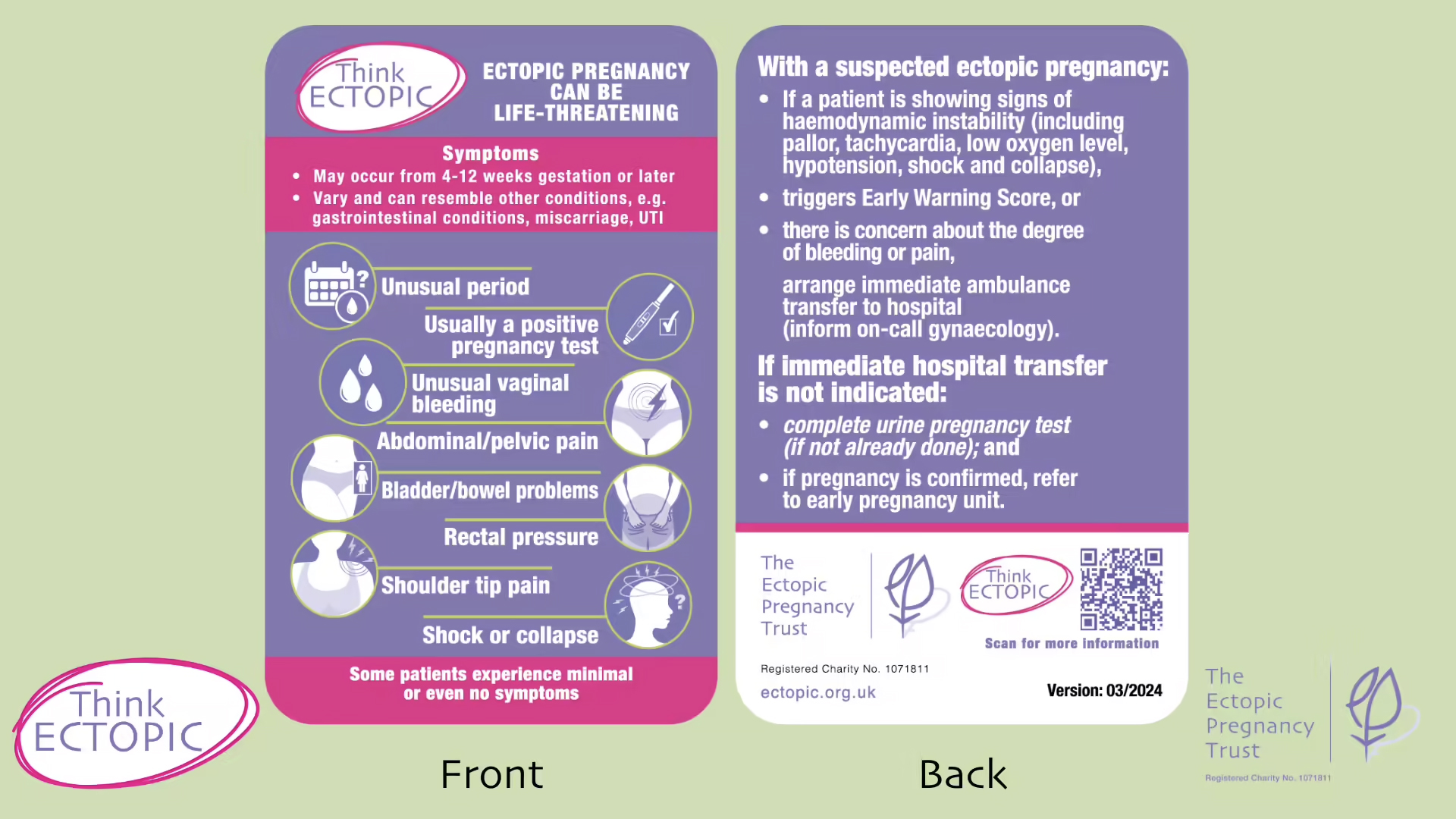

The MBRRACE-UK report emphasises the need to Think Ectopic, which aligns with a national campaign led by The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust, endorsed by the RCGP. At the heart of the campaign is an ectopic pregnancy biocard which reminds healthcare professionals about the signs of ectopic pregnancy and time critical next steps.

Figure: Think Ectopic Bio Card. The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust. Reproduced with permission.

Request free copies of the card from The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust.

References

- NICE CKS. Ectopic pregnancy. Feb 2023.

- Anzhel S, Mäkinen S, Tinkanen H et al. Top-quality embryo transfer is associated with lower odds of ectopic pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022 Jul; 101(7): 779-786.

- MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care. Nov 2022.

- MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care. Oct 2024.

- NICE. NG126. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. Aug 2023.

- Ralph LJ, Foster DG, Barar R, et al. Home pregnancy test use and timing of pregnancy confirmation among people seeking health care. Contraception. 2022 Mar; 107: 10-16.

- University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust. Laparoscopic sterilisation. Dec 2022.

- FSRH. Intrauterine contraception. July 2023.

No-one expects their child to die before them – it isn’t the natural order of things.

From miscarriages to stillbirths and from perinatal deaths to deaths in childhood, the death of a child is a unique type of loss.

Pregnancy loss is the most common form of child loss. It is currently estimated that one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage1 so it is something many parents will experience. Even though they may have never been able to get to know their child, they will still feel a huge loss. They grieve the potential to get to know that child and the life they would have had. Many parents will also feel a sense of guilt following a miscarriage so it is important to look out for any hint of this and to reassure the parent that this was not their fault.

When a parent loses a child of any age, in that split second, their world is changed forever. They lose not only their child, but also many of the social networks linked to their child. They lose the potential to see that child grow up and if the child was their only child, their identity as a parent and the chance to become a grandparent. They lose not only the present but also the future. The loss of a child for this reason is very different to other types of grief.

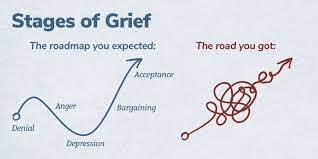

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

In 2007, Harper et al showed that in the 15 years after losing a child or having a stillbirth, bereaved mothers were 2-4 times more likely to die than non-bereaved mothers and that the excess risk persists for 35 years after the bereavement, though the magnitude of the risk drops with time. The increased risk persists for three years for fathers, though clearly they have an increased risk of being widowed for much longer. The reasons for this phenomenon are not clear, but could involve immunosuppression due to severe stress, maladaptive coping strategies such as alcohol misuse, pre-existing poor health which may have contributed to the child bereavement, mental ill-health following bereavement, or bereaved parents presenting later with their own physical health problems. Further research into this area would be useful. The relevance to general practice is probably that we should be aware of this risk and make particular use of the GP ‘spidey sense’ when dealing with this group of patients. Never ignore your gut feeling as a GP – it has been shown to be reliable3.

I am writing this blog from personal experience, after losing my four-year-old daughter Grace to cancer in 2014. My personal experiences have helped me to support many other families in similar situations and in 2018 I wrote an eLearning course for the RCGP, designed to provide GPs with the tools to support patients who have experienced a loss during pregnancy, or the death of an infant or child. Each family needs something different, but the overwhelming message is that having someone simply able to be there for them as a point of contact, it can make a big difference.

When a family loses a child, it also has a significant impact on their siblings. Life for their surviving siblings never returns to normal so it is important to remember that their bereavement will affect many aspects of their life and behaviour.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

Often, a few simple measures taken by a practice can make a sizable difference to help families realise that they are not alone. When the practice has been informed of a child death, it is important to contact the family, by phone if possible. This need only be brief, but families do appreciate this and remember this contact down the line.

Families should be provided with a named GP, and alerts placed on the notes of both parents and all siblings so practice staff and professionals can be aware of the history without the family needing to repeat themselves each time.

If possible, enable bereaved parents and siblings to make appointments at minimal notice for a limited time. The death of a child can plunge a family into chaos meaning things are easily forgotten or they may need to be seen quickly to help with acute emotional situations.

Ensure that all professionals are notified. Check that electronic alerts inviting the deceased child for immunisations, reviews or other routine care have been turned off. It is also useful to familiarise yourself with the services and support that are available in your local area to signpost families to as required.

General Practice is extremely busy at the moment, but these simple measures are relatively time efficient and can make a real difference to these families.

References

1 Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O'Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med, 1988; 319(4): 189-94.

2 Harper M, O'Connor RC, O'Carroll RE. Increased mortality in parents bereaved in the first year of their child's life. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2011; 1(3): 306-9.

3 Friedemann Smith C, Drew S, Ziebland S et al. Understanding the role of GPs’ gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. British Journal of General Practice 2020; 70 (698): e612-e621.

'Stages of Grief' image used with permission from WPSU's Speaking Grief project.