Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

It wasn’t what I wanted in my stocking as a child, but as a full-blown contraception nerd, I’m excited at the December 2025 launch of the new UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use (UKMEC)1. Published by the College of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (CoSRH), formerly the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, the UKMEC is the gold-standard document on contraceptive safety.

Before getting into the changes, there are some important basics to remember:

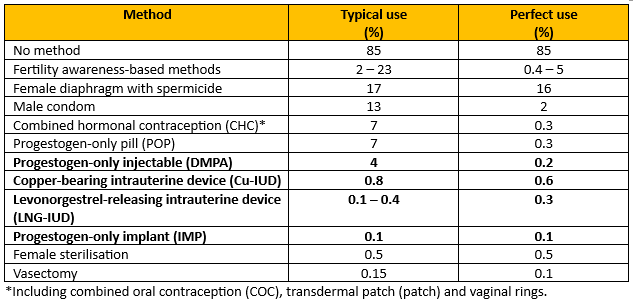

- The UKMEC is about safety, not efficacy, although the document does include an efficacy table (figure 1).

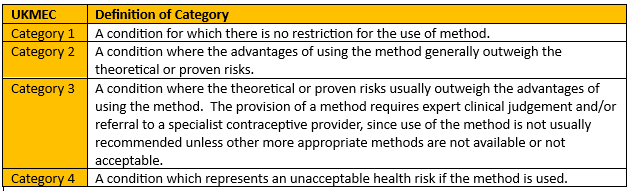

- Methods are categorised from 1-4, as per figure 2. 1 and 4 are simple – no problem to use or absolutely contraindicated respectively; it’s in the 2s and 3s that your clinical judgment will be important.

- The UKMEC is one place where 2 + 2 ≠ 4. Two category 2s doesn’t automatically mean an absolute contraindication, but if they are both in the same area, it does signal a cumulative risk and the need for caution. More than one category 3 ‘may pose an unacceptable risk’.1

- Some methods have different numbers for initiation or continuation, reflecting the different risks attached to starting a method or continuing one that is already being used.

- If a condition isn’t covered in the UKMEC, that doesn’t necessarily mean that all contraception is safe for use. Consider seeking advice from secondary care, or, if you are a CoSRH member, submit an evidence request to their Clinical Effectiveness Unit and they will summarise the available evidence for you to use alongside your clinical judgment.2

- The UKMEC is intended to be applied only to contraceptive use. If a woman is getting an extra benefit from her method (for example the management of endometriosis), that may affect your risk/benefit calculation.

Figure 1 - Recreation of Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy within the first year of year of use with typical use and perfect use.

Figure 2 - Recreation of Definition of UKMEC categories

The key changes are summarised in figure 3.

|

Topic(s) |

Key change |

|

Chronic kidney disease. Multiple sclerosis.

|

|

|

Use of e-cigarettes. Sickle cell trait. |

|

|

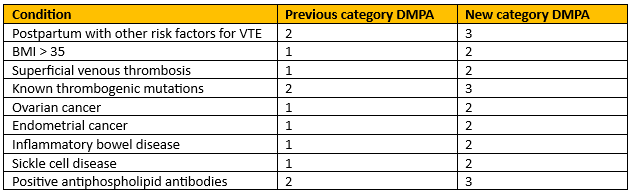

Multiple category changes for the depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injection. |

|

|

Depression and anxiety |

|

|

Stroke |

|

|

Breast cancer |

|

|

Human papilloma virus and sexually transmitted infections. |

|

|

HIV |

|

|

Hypertension |

|

|

Multiple risk factors for VTE and CVD |

|

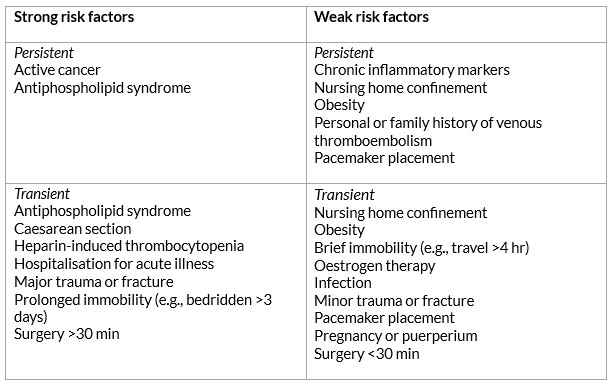

Figure 4 - Recreation of Conditions with increased risk of thrombosis.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Regarding CKD, only the most seriously affected are included – patients who either have nephrotic syndrome or are on dialysis. This cohort should not use CHC (due to VTE risk), and DMPA is now UKMEC 3. This is because DMPA is associated with a small loss in bone mineral density, reversible on stopping3 and those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are already at risk of osteoporosis4. All other methods are a UKMEC 2.

Multiple sclerosis

The risk from MS is mainly to do with immobility as a risk factor for VTE, so most methods are a UKMEC 1 for those without prolonged immobility, the exception being DMPA, which is a 2, because those with MS have a greater risk of fracture than the greater population. With prolonged immobility, DMPA remains a 2 and CHC is a 3.

When prescribing hormonal contraception, it is common to be asked about whether it will cause mood changes. Mood alteration is listed as a common or very common side-effect in the BNF for some combined and progestogen only methods5,6,7 but depression was listed in the previous UKMEC as a category 1. It has been removed from this edition as a category and replaced with a statement about the effects of hormonal contraception in those with anxiety or mood disorders.

The key points are as follows8:

- There is no clear evidence that any form of hormonal contraception worsens or improves mood.

- Most evidence is from observational studies, which often have confounding factors, and do not usually focus on women with pre-existing mental health conditions.

- Some patients do report mood change during the use of hormonal contraception; this may not represent direct causation.

- Healthcare professionals should explore other possible contributing factors and consider alternative contraception if the patient feels that their mood has been adversely affected by their contraception.

- Patients with pre-existing anxiety or depression should monitor their mood when starting hormonal contraception.

There are two sections on multiple risk factors – one for CVD and one for VTE; the section on multiple risk factors for VTE has been updated in this iteration. The UKMEC signposts to NICE for a full list of risk factors but gives examples which include cancer, inflammatory disorders, recent trauma or surgery and being in the postnatal period. Someone with multiple risk factors for VTE is UKMEC 4 for CHC, 3 for DMPA and 1 for all other methods.

The UKMEC is a long document; it will take time for the changes to fully bed in, but practices will need to decide how they implement it, particularly for those already using contraception. Reviewing all those using DMPA at the time of their next injection, and everyone else at their annual review would be a good start and hopefully we will all be fully up to date with it long before the next one comes along in a decade or so!

References

- CoSRH. UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC). Dec 2025.

- CoSRH. Members’ Evidence Request Service.

- CoSRH. Progestogen-only Injectable Contraception. July 2023.

- National Osteoporosis Guideline Group UK. Clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. 2024.

- BNF. Ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel.2025.

- BNF. Desogestrel.2025.

- BNF. Etonogestrel. 2025.

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Chickenpox is a common and unpleasant childhood illness. More than 90% of the population have acquired antibodies to the causative infection (the varicella zoster virus) by the age of 151. For many it is a self-limiting illness (often leaving behind scars when scratching cannot be resisted), but there is a risk of significant complications, as listed in the box below. Those at a higher risk of complications include adults, adolescents, children aged under one, pregnant women and immunocompromised people. Around 20 people per year die of chickenpox in the UK3 and there is a risk of neonatal death if a susceptible woman contracts chickenpox in the week before delivery3.

|

Complications of chickenpox1: |

|

The economic cost to the UK of parents taking time off work to provide childcare to their children with chickenpox is estimated to be over £24 million per year4 – the difficulties of taking prolonged time off work for childcare perhaps explains why one survey (the satisfyingly named SPOTTY study5 showed that 73% of UK paediatricians surveyed had privately vaccinated their child against varicella. As the author of this blog discovered last year, chickenpox can also wreak havoc if it appears two days before a family holiday!

Until recently, NHS chickenpox vaccination has only been offered to a small group of people. These include susceptible healthcare staff (including non-clinical, e.g. cleaners, porters etc), laboratory staff who work with the varicella virus, and close household contacts of immunocompromised patients, such as siblings of a child with leukaemia, or a child whose parent is having chemotherapy3. For patients who are due to start immunocompromising medication and are susceptible to varicella, vaccination is offered if there is enough time to give the two-dose course before the medication has to be started3.

This will change in January 2026, when universal vaccination begins on the NHS in all four countries of the UK 6,7,8,9. Details of the programme are as follows10

- Offered to children at the age of 18 months.

- Given with measles, mumps and rubella as the MMRV vaccine.

- Booster at three years and four months of age.

- One-dose catch-up programme for children born between 1.1.2020 and 31.8.22, who can access the vaccine until the end of March 2028.

- No NHS offer of a single varicella vaccine.

- The MMR vaccine without varicella will no longer be available for the NHS routine childhood immunisation programme, although it will still be available for those who need the MMR vaccine in adulthood. Children who did not have MMR at the usual time and are brought later in childhood should be caught up with MMRV.

So why have the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), who decided against universal childhood varicella vaccination in 2009, changed their mind? The original decision was made on cost-effectiveness grounds, with an estimate that it would take 80-100 years for the programme to become cost-effective11. The new decision has largely been based on two factors – a review of the prevalence of chickenpox complications, and a change in the way we think about shingles in adults.

The JCVI believe that the cost of chickenpox complications has probably been underestimated, affecting their assessment of of cost-effectiveness of the vaccine. It is likely that many people admitted with complications of chickenpox have had their admission coded with the name of the complication (pneumonia, meningitis, cellulitis etc) but that the code for chickenpox was not added, so the two weren’t linked for the purposes of cost calculation11. The availability of the four-virus MMRV vaccine has also improved the cost-effectiveness calculation, as there is no need for another nurse appointment, over and above the one which would have been necessary for the MMR vaccine.

Another concern in 2009 was that vaccinating against chickenpox would put older adults at an increased risk of shingles, caused by reactivation of the varicella virus. The theory was that those who have had chickenpox in the past have their immunity regularly boosted by coming into contact with children who have varicella (which is infectious during the prodrome, before spots have appeared and children are kept at home) and that reducing chickenpox incidence in children would increase shingles in middle-aged adults. At the 2023 review it was clear that data from the United States (who have vaccinated against chickenpox since 1995) did not support this hypothesis11 – and we also now have the NHS shingles vaccination, which was not offered in 2009.

Vaccine hesitancy remains an issue in the UK, with only 85% of English 5 year olds having had two doses of MMR – uptake in some communities is significantly lower than that12. It will be interesting to see whether the addition of varicella to the MMR vaccine reduces uptake further, due to unwarranted nerves about multiple vaccine, or whether the benefits of not having to look after an irritable child with chickenpox will encourage people to vaccinate, in turn increasing MMR uptake.

References

- NICE CKS. Chickenpox. Nov 2023.

- Oxford Vaccine Group. Chickenpox (varicella). Nov 2023.

- UKHSA. Varicella: the green book, chapter 34. Sept 2024.

- LSE. The true cost of chickenpox: at least £24 million in lost productivity a year in the UK. April 2022.

- O'Mahony E, Sherman SM, Marlow R et al. UK paediatricians' attitudes towards the chicken pox vaccine: The SPOTTY study. Vaccine. 2024 Sep 17; 42 (22): 126199.

- DHSC. Free chickenpox vaccination offered for first time to children. Aug 2025.

- Department of health. Chickenpox vaccination to be offered to children in Northern Ireland from 2026. Aug 2025.

- NHS Scotland. Changes to the Scottish Childhood Vaccination Schedule from 1 January 2026 (phase 2) – introduction of a routine Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox) vaccine. Nov 2025.

- NHS Wales. New Chickenpox (Varicella) Vaccination Programme in Wales.

- UKHSA and NHSE. Introduction of a routine varicella (MMRV) vaccination programme for children at one year and at 18 months. Oct 2025.

- DHSC. JCVI statement on a childhood varicella (chickenpox) vaccination programme. Nov 2023.

- UKHSA. Evaluating the impact of national and regional measles catch-up activity on MMR vaccine coverage in England, 2023 to 2024.Aug 2024.

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) - whether it presents as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) - is a common presentation in primary care: its annual incidence is 1-2 cases per 1000 population, rising significantly with increased age. In Europe, pulmonary embolism accounts for 8–13 deaths per 1000 women and 2–7 deaths per 1000 men aged 15–55 years1. Thrombosis UK suggests that 1 in 20 people will experience a VTE in their lifetime2. NHS Resolution reports that from 1 April 2012 until 31 March 2022 it documented 687 closed claims relating to VTE injuries across the clinical negligence indemnity schemes, with total damages paid of £23,780,1793.

Significant risk factors such as major surgery, prolonged immobilisation, and major trauma account for approximately 20% of all venous thromboembolism episodes, though the commonest strong persistent risk factor is active cancer, accounting for approximately 20% of incidents. Table 1 lists persistent and transient risk factors for VTE.

Table 1: Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, Rodger MA. Venous thromboembolism. The Lancet 2021 Jul; 398(10294): 64–77.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with a deep vein thrombosis can present with leg pain (80–90% of patients), swelling (80%), localised tenderness on palpation (75–85%), prominent collateral superficial veins (30%) and redness (25%). 30% - 60% of patients presenting with a proximal (above the knee) DVT already have a silent pulmonary embolism. A review paper from Canada described that the majority of symptomatic episodes of lower extremity DVTs start in the distal veins, with symptoms being uncommon until there is involvement of the proximal veins. They reported that in a consecutive series of 189 outpatients with a first episode of venographically diagnosed DVT, where symptoms were all distal, 89% had proximal thrombi4. Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT) – arising in the brachial, axillary or subclavian veins - is thought to account for about 10% of all DVTs5.

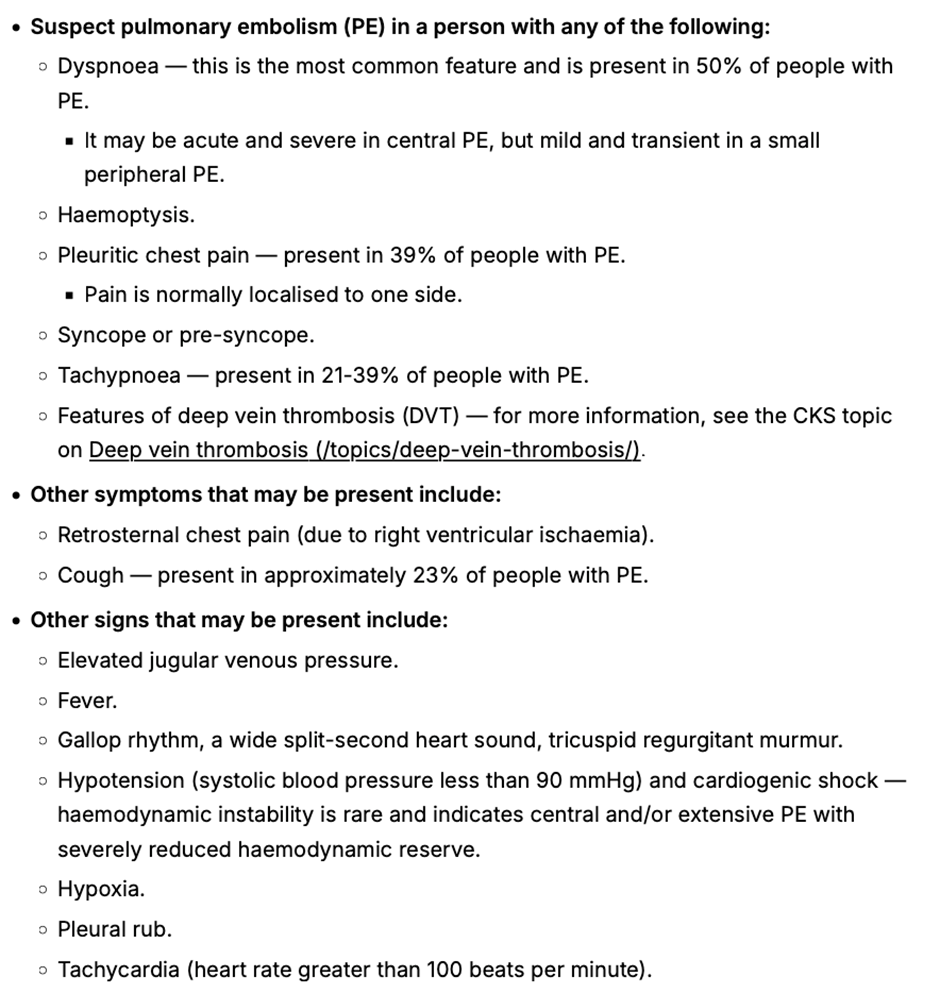

Pulmonary emboli often present insidiously and often without the classic triad of pleuritic chest pain, shortness of breath and hypoxia. There are a large number of case reports showing patients complaining of nagging symptoms for weeks before succumbing to pulmonary embolism, with 40% of these patients being seen by a physician in the weeks prior to their death6. A retrospective cohort study from 2016 showed that 25% of patients with a PE presenting in primary care had an average delay of 15.7 days to diagnosis7. Table 2 lists the range of symptoms that the NICE CKS suggests point towards a PE.

Table 2: When to suspect pulmonary embolism from NICE CKS Pulmonary embolism 2023.

Diagnosis

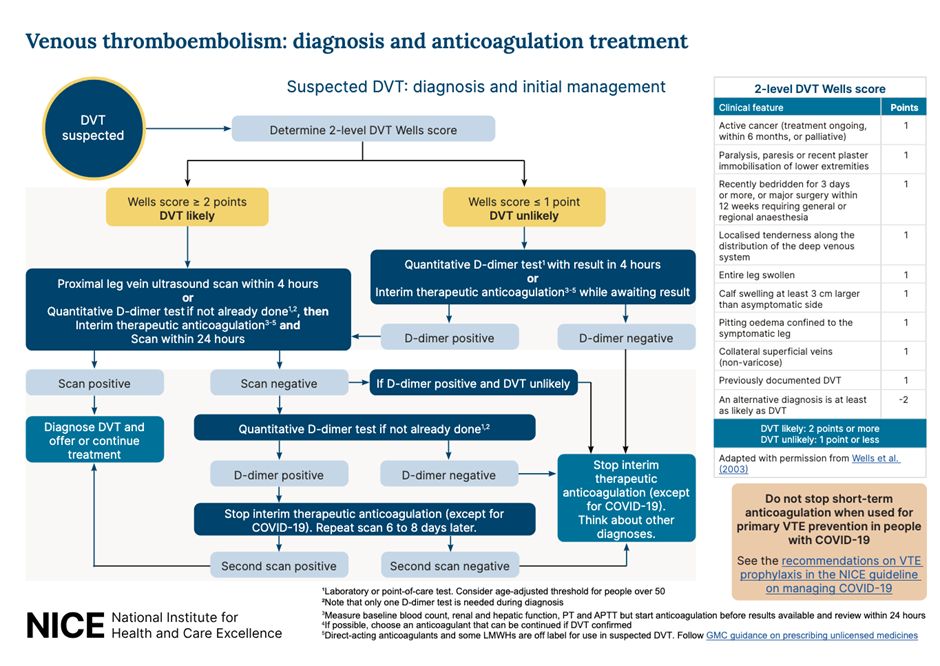

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updated their recommendations for the diagnosis and management of VTE in 2023. It suggests that patients with symptoms that might indicate a DVT should be examined and accessed via a 2 - level Wells Score. If the Wells score is 2 or above, these patients should be offered a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan, with the result available within 4 hours if possible. If the scan is negative, a D-Dimer should be arranged. For those patients that can’t access a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan within 4 hours, offer a D‑dimer test, then interim therapeutic anticoagulation and a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan with the result available within 24 hours. For those patients with a Wells score of 1 or less, arrange a D dimer test with the result available within 4 hours, or, if the D dimer test result cannot be obtained within 4 hours, offer interim therapeutic anticoagulation while awaiting the result. If the D-Dimer test is positive, arrange an ultrasound and add interim anticoagulation if not already started (see Table 5)

Table 3: Recommended workflow for suspected DVT. NICE 2023

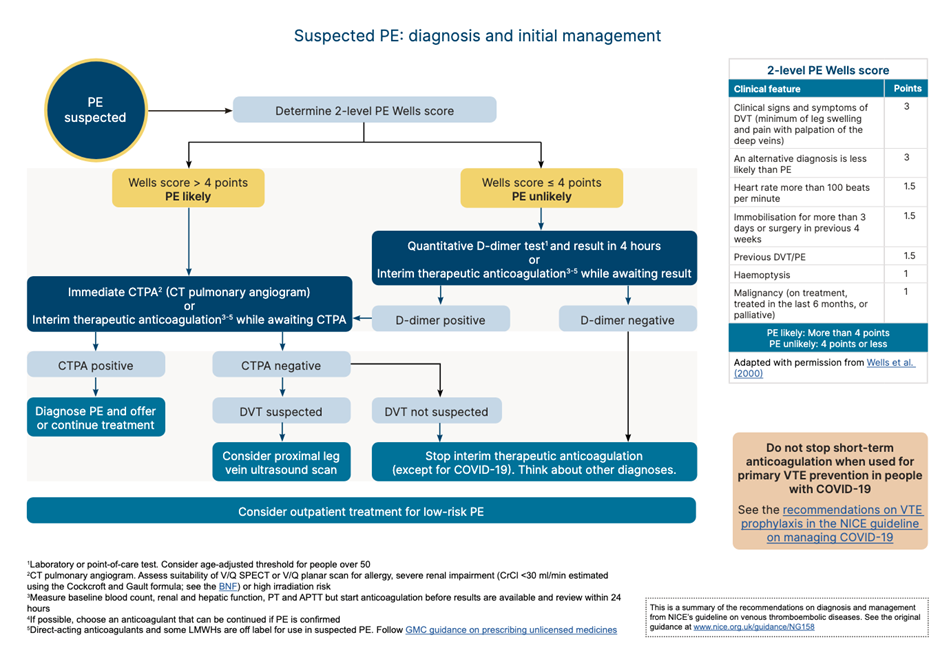

For people who present with signs or symptoms of a PE, arrange a physical examination, take a medical history and offer a chest x-ray (if available in your setting) to exclude other causes. If, after assessment and investigations, the clinical suspicion for a PE is low and other diagnoses are more likely, consider using the pulmonary embolism rule–out criteria to help determine whether any further investigations into a PE are necessary. This questionnaire has not been validated for people with COVID-19.

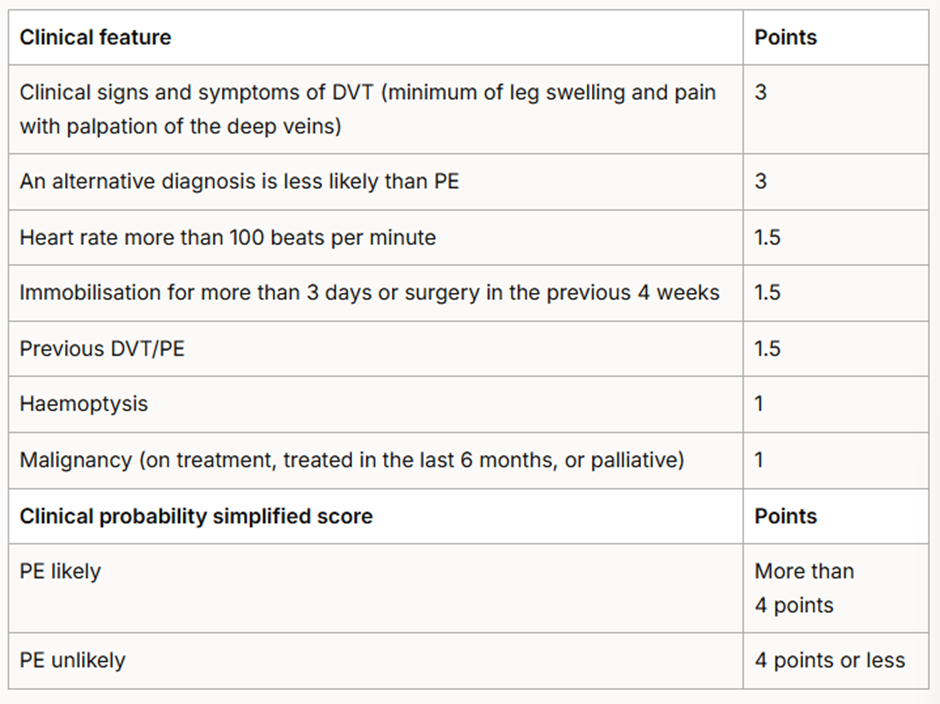

If a PE is suspected, the 2 level PE Wells score (see table 6) should be used.

If a patient scores 4 or more, NICE suggests a range of different imaging options arranged in secondary care, with anticoagulation to be initiated depending on the outcomes.

If the Wells score is 4 or less, NICE suggests D-Dimer testing with the result being available within 4 hours, or interim anticoagulation if this can’t be arranged. If the D-Dimer is positive, imaging will have to be arranged8

Table 4: Recommended workflow for PE. NICE 2023

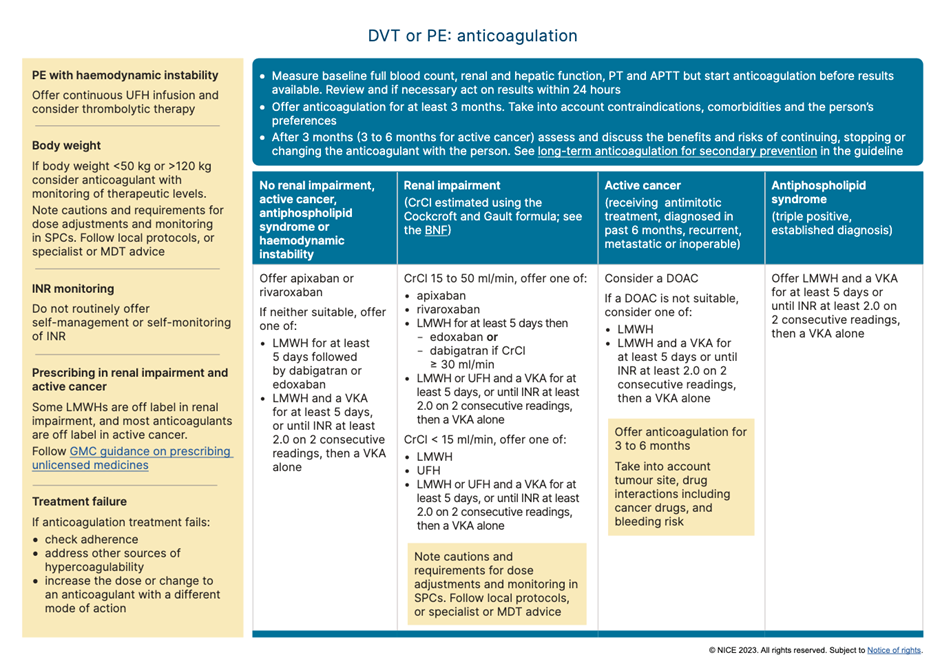

Table 5: Recommendations for anticoagulation for suspected/confirmed VTE. NICE 2023

In day-to-day practice every locality will have their own protocols and referral pathways for the management of suspected VTE in the community. Nevertheless it is important to remember that patients who score 1 or below on the DVT Wells questionnaire, should still have a D-Dimer test. This was highlighted by a case that a coroner shared with the RCGP, in which a patient tragically died four weeks after an initial assessment for calf swelling; while the Wells score was applied, the patient did not have a D-Dimer. The patient then developed respiratory symptoms and was seen by various healthcare practitioners over a 4 week period before suffering a cardiac arrest caused by a large PE.

The vast majority of patients with VTEs are being expertly managed in cooperation between primary and secondary care. General practitioners are experts in managing diagnostic uncertainty - an inevitable part of their profession - and VTE presentations can certainly can test this vital skill. Acknowledging the broad scope of symptoms and subsequent use of the local pathways for VTE can nevertheless increase the pickup rate further, improving the safety of our patients.

Table 6: Two-level PE Wells score. NICE 2023 Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing.

References

- Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, et al. Venous thromboembolism. The Lancet . 2021 Jul; 398 (10294): 64–77.

- Thrombosis UK.

- Venous thromboembolism. NHS Resolution. 2023.

- Kearon C. Natural History of Venous Thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003 Jun 17; 107 (90231): 22I-30.

- Ageno W, Haas S, Weitz JI, et al. Upper Extremity DVT versus Lower Extremity DVT: Perspectives from the GARFIELD-VTE Registry. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2019 Jun 10; 119 (08): 1365–72

- Safi M, Tajik Rostami R, Taherkhani M. Unusual presentation of a massive pulmonary embolism. J Teh Univ Heart Ctr 2011; 6( 1): 41-44.

- Walen S, Damoiseaux RA, Uil SM, et al. Diagnostic delay of pulmonary embolism in primary and secondary care: a retrospective cohort study. British Journal of General Practice. 2016 Apr 25; 66 (647): e444–50.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NG158 Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing 2023.

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Pneumonia is defined as an infection of the lung tissue, in which the alveoli become filled with micro-organisms, fluid and inflammatory cells, affecting the function of the lungs1. Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) has a mortality rate of around 1% in those who are managed in primary care, rising to up to 14% for those admitted to hospital and to 30% for those who need intensive care1. GPs need to risk stratify and make logical decisions as to who can be managed in the community, and who needs referral and consideration of admission.

An experienced GP will be used to assessing severity of acute infection. We make a clinical assessment, starting with an overall look at the patient (do they look unwell or otherwise make our antennae twitch?), assessment of vital signs such as pulse, respiratory rate, temperature and oxygen saturations, and consideration of co-morbidities such as immunosuppression. The NICE guidance on pneumonia2, published in September 2025, recommends the more formal CRB65 tool, once we have made a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia.

Technology is available to measure C-reactive protein (CRP) as a point of care test in primary care, to help support or refute a diagnosis of inflammation, as occurs in an infection such as pneumonia. A 2016 NICE MedTech innovation briefing3 noted that primary care CRP testing can reduce antibiotic prescribing and referrals for chest x-ray, but that the sensitivity did not rise above 55% (and could be as low as 20% depending on the threshold used). Specificity was better, ranging from 73 – 99%. In the nine years since that briefing, the test has not become widely available, with barriers including cost, lack of commissioning enthusiasm and concern about the evidence base for effectiveness and value for money. A 2025 qualitative review4 comparing the UK with Sweden, the Netherlands and Canada, found that uptake of primary care CRP testing was higher in the other countries, but that clinicians didn’t feel that it had made a huge improvement to their assessment of patients with possible pneumonia, with some saying that the introduction was a policy failure, and the test over-used. Other studies have shown that CRP use is associated with increased antibiotic prescribing, rather than helping to reassure that antibiotics aren’t needed, and that this is particularly associated with systems where a CRP is checked before the patient is seen, resulting potentially in spurious high results in those with a low pre-test probability of bacterial infection5. NICE does not discuss primary care CRP in its latest guideline2, but where it is being used the Primary Care Respiratory Society suggests cut-offs of 20 and 40 mg/L – do not prescribe antibiotics with CRP<20, consider prescribing with CRP of 20-40 if there is purulent sputum, and prescribe with CRP>406.

The CRB65 scoring system is outlined in the box below and the results predict the risk of death in the next 30 days. Zero is low risk (<1%), 1 or 2 intermediate risk (1 – 10%) and 3 or 4 high risk (>10%).

CRB65 score – one point for each of the following:

- Confusion (new disorientation in person, place or time, or a score of ≤8 on an abbreviated mental test).

- Respiratory rate ≥30.

- Blood pressure ≤60 mmHg diastolic or 90 mmHg systolic.

- Age ≥65.

NICE write ‘guidelines not tramlines’7, and this guideline acknowledges the holistic nature of our assessment, advising the use of clinical judgment along with the CRB65 score, which can be affected by other factors such as comorbidities or pregnancy. NICE advises considering referral with a CRB65 score ≥2, and that those with a CRB65 score of 1 might benefit from an assessment in a same-day emergency care unit (which is in any case often where those referred to hospital will end up) or by being referred to a virtual ward or hospital at home service. Those with a score of zero can be managed in primary care, with appropriate safety-netting to return if symptoms deteriorate. Any signs of significant complications, such as heart failure, would lower the threshold for referral. We should have a lower threshold for children and young people (those aged under 18), considering referral or specialist advice for every patient.

For those not admitted, we would usually treat pneumonia with antibiotics in the community, to be started as soon as possible after the clinical diagnosis has been made2. Whilst some causes are viral, the majority of pneumonia has a bacterial cause1, and we cannot reliably differentiate between the two. The commonest bacterial cause is Streptococcus pneumoniae, with other responsible organisms including Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and the atypical Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Those who are immunocompromised, or who have had multiple recent courses of antibiotics, may be more likely to have an unusual or drug-resistant bacteria (or a fungal infection such as Aspergillus) as a cause for their pneumonia8,9; pneumonia in those with an unsafe swallow may be related to aspiration of stomach contents10.

NICE emphasises the need for only a five day course of antibiotics for adults and three days for children aged up to 11, with a longer duration only when clinically necessary. This may be because they have had a temperature in the last 48 hours of the five day course, or that they continue to have a sign of clinical instability, such as (in adults) systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, heart rate >100 bpm, respiratory rate >24 breaths per minute or oxygen saturations <90% on air. These parameters, if present after five days of antibiotics, might make us re-visit the decision to keep the patient at home. The suggested first-line antibiotic for low-severity disease is amoxicillin, with doxycycline or clarithromycin as second-line, and erythromycin for pregnant women. For moderate severity disease the choice is largely the same, although clarithromycin moves to first line if an atypical bacterial cause is suspected. Those with high-severity disease are likely to be in hospital, but if treated in the community then a combination of co-amoxiclav and clarithromycin are first line, with erythromycin in pregnancy and levofloxacin as an alternative for those with penicillin allergy (bearing in mind the MHRA advice on quinolones11).

Distinguishing between typical and atypical bacterial causes without a sputum sample is by no means an exact science; those with an atypical bacteria may have more prolonged or prominent constitutional symptoms (headache, malaise, sore throat, fever) and may be less likely to have clear consolidation on auscultation of the chest. Atypical infection can come in epidemics, with many cases clustered together and then none for several years and is more common with increasing age and in those who live in enclosed spaces such as boarding schools or military barracks. Outbreaks of one particular atypical bacteria, Legionella pneumophila are associated with contaminated water and air-conditioning systems and another, Legionalla longbeachae is associated with exposure to contaminated soil mixtures12. Consideration of an atypical bacteria should be given when the patient doesn’t respond to an apparently appropriate first-line choice of antibiotic, and where there is a history of staying in a hotel or resort where exposure may be more likely.

Further reading and useful resources

- RCGP eLearning modules on Aspergillus and pneumonia.

- NICE guidance on pneumonia.

- StatPearls articles on aspiration pneumonia, atypical pneumonia and pneumonia in the immunocompromised patient.

- Patient information leaflet and NHS webpage on pneumonia.

References

- NICE CKS. Chest infections – adult. Jan 2025.

- NICE. NG250. Pneumonia: diagnosis and management. Sept 2025.

- NICE. MIB81. Alere Afinion CRP for C-reactive protein testing in primary care. Sept 2016.

- Glover RE, Pacho A, Mays N. C-reactive protein diagnostic test uptake in primary care: a qualitative study of the UK's 2019-2024 AMR National Action Plan and lessons learnt from Sweden, the Netherlands and British Columbia. BMJ Open. 2025 Aug 31;15(8):e095059.

- Payne R, Mills S, Wilkinson C et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing in general practice out-of-hours services: tool or trap? Br J Gen Pract. 2025 Aug 28;75(758):388-389.

- Primary Care Respiratory Society. The place of point of care testing for C-reactive protein in the community care of respiratory tract infections. Summer 2022.

- Reeve J. Avoiding harm: Tackling problematic polypharmacy through strengthening expert generalist practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Jan;87(1):76-83.

- Aleem MS, Sexton R, Akella J. Pneumonia in an Immunocompromised Patient. [Updated 2023 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Assefa M. Multi-drug resistant gram-negative bacterial pneumonia: etiology, risk factors, and drug resistance patterns. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2022 May 5;14(1):4.

- Sanivarapu RR, Vaqar S, Gibson J. Aspiration Pneumonia. [Updated 2024 Mar 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- MHRA. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: must now only be prescribed when other commonly recommended antibiotics are inappropriate. Jan 2024.

- Nguyen AD, Stamm DR, Stankewicz HA. Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia. [Updated 2025 Apr 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

Written by Dr Emma Nash

The Chief Medical Officer’s low-risk drinking guidelines recommend that adults do not drink more than 14 units of alcohol a week, spread evenly over three or more days.1

Although around 20% of the population report drinking no alcohol at all, a significant proportion of adults regularly drink over the recommended amount, ranging from 9% of Northern Irish women to 32% of English men.2 The consequences of excessive alcohol consumption are significant, with 10,473 deaths from alcohol-specific causes in the UK in 20233; many more are alcohol-related.

The public health approach ‘Making Every Contact Count’ (MECC)4 promotes the importance of making the most of opportunities to effect behaviour change. It encourages the use of routine interactions with people to offer brief advice and support them in making positive changes to their physical and mental health and wellbeing. Alcohol brief interventions are one such example.

In the context of alcohol, a brief intervention can be described as: “a short, evidence-based, structured conversation about alcohol consumption with a patient that seeks in a non-confrontational way to motivate and support the individual to think about and/or plan a change in their drinking behaviour in order to reduce their consumption and/or their risk of harm”.5

Brief interventions take 5-15 minutes to deliver and are ideally reinforced over further sessions. Multiple models exist, but ultimately the purpose is to focus the person’s attention on their lifestyle, highlight the reasons for change and potential strategies to do it, and empower the person to make the change. Whilst time constraints make a GP consultation challenging to deliver this, even a very brief intervention, with follow-up to discuss further, is useful.

Enquiring is the first stage – simple questions about alcohol consumption, or something more structured such as an AUDIT-C – can help identify where there is a problem, or at least bring it to mind. Behavioural change is a process rather than an event and even moving from the pre-contemplation to the contemplation stage of change is positive.

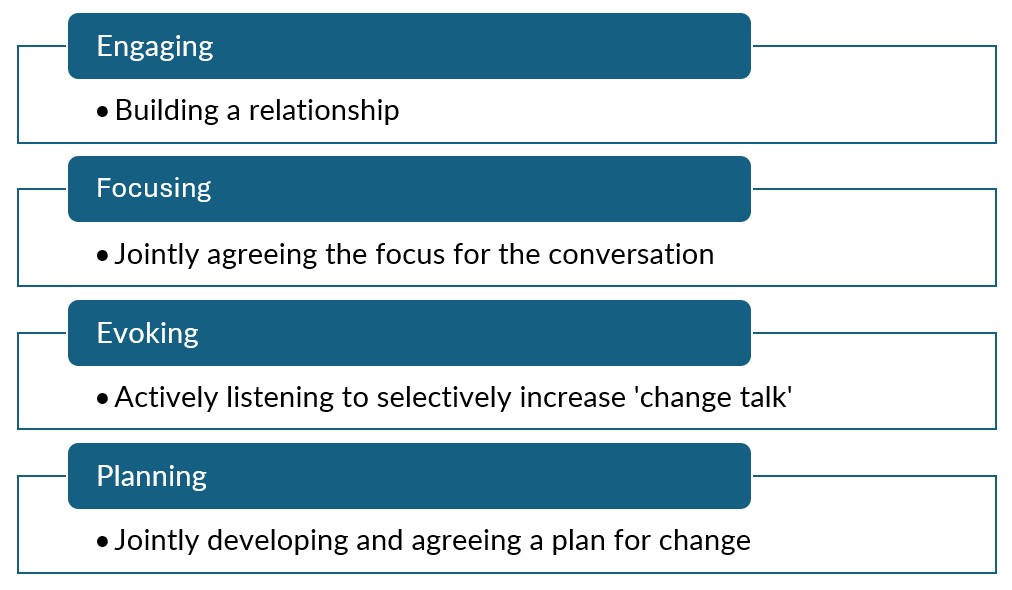

The brief intervention itself varies in form and needs specific training dependent on the model used. However, a common theme is motivational interviewing. Key elements of motivational interviewing include an emphasis on patient autonomy and patient-centred collaborative approach built on acceptance. One model of motivational interviewing by Miller and Rollnick6 describes four processes:

The extent to which motivational interviewing features in the brief intervention depends on the particular model chosen.7

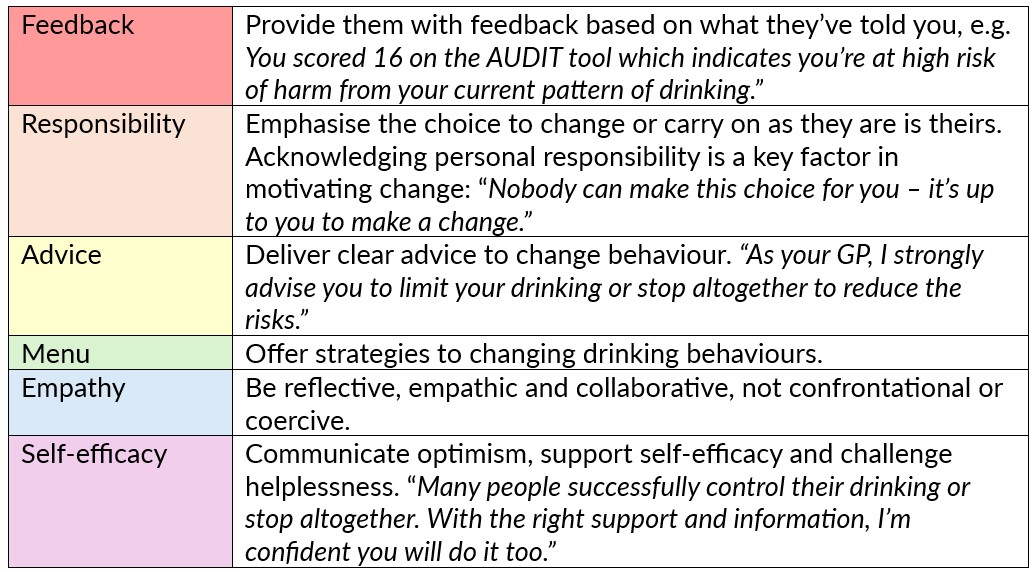

One example of a brief intervention tool is the FRAMES model.8,9

What you are able to suggest in the ‘Menu’ section depends on what is available locally in terms of support. However, behavioural strategies may include setting personal drinking limits and sticking to it; alternating alcoholic drinks with soft drinks; switching to low alcohol drinks; having regular alcohol-free days; identifying high risk situations for heavy drinking and creating a management plan; engaging in alternative activities to drinking.

Whilst these interventions can appear complex or arduous, they are only brief and are designed to be delivered in snippets, with reinforcement. The evidence base for the use of brief interventions is good, particularly in a primary care setting10,11 and have the potential to have a significant impact on the future health of our patients.

Further reading

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Conduct a brief intervention: Build motivation and a plan for change.

NHS England. eLFH - Alcohol identification and brief advice.

ScotPHO. Alcohol: treatment for alcohol misuse.

References

- English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish Governments. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines. 2016.

- Alcohol Change UK. Alcohol statistics. Updated 2025.

- Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK: registered in 2023. 2025.

- Public Health England, NHS England, Health Education England. Making Every Contact Count (MECC): Consensus statement. 2016.

- Scottish Government. Local delivery plan: Alcohol brief interventions. National guidance 2019-2020. 2019.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing, 3rd ed. Helping people change. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2012.

- World Health Organisation. Alcohol brief intervention training manual for primary care. WHO, 2017.

- Bien T, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction, 1993. 88(3): p.315-336.

- Drug and Alcohol Clinical Advisory Service. Fact sheet. FRAMES – Brief intervention for risky or harmful alcohol consumption.

- World Health Organisation. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Luxembourg: WHO, 2014.

- Platt L, Melendez-Torres GJ, O'Donnell A, et al How effective are brief interventions in reducing alcohol consumption: do the setting, practitioner group and content matter? Findings from a systematic review and metaregression analysis. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e011473.

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

There is no question that general practice is an increasingly stressful profession, with ever growing demands placed on GPs while battling with diminishing financial and staffing resources. Days at work that just won’t end, never-ending workload and little control over our working lives can affect even the most resilient of practitioners. Throw in the constant battle with complaints and medicolegal issues and it’s no wonder that the prevalence of burnout, depression, low self-esteem and anxiety are significantly higher in the medical profession compared with the general population1. The numbers are startling: An MDDUS survey from 2024 reported 71% of general practitioners suffering from compassion fatigue and 65% suffering from burnout2. A PULSE survey from 2025 found that more than 54% of primary care doctors had to reduce sessions due to stress3. Unfortunately doctors aren’t great patients: we tend to downplay the severity of our symptoms and under-diagnose conditions in ourselves and often ignore the fact that we should seek help4.

For some time now, but particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, attempts have been made to prevent burnout syndrome through individual and systemic approaches within the primary care workforce. Various psychological interventions were developed to empower professionals coping with increasing stress and burnout. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) are effective in reducing stress and promoting self-care and wellbeing: there is a growing body of research evidence that these can increase job satisfaction and even improve patient outcomes. Mindfulness has a well-established evidence base showing efficacy in improving the psychological wellbeing in both clinical and non-clinical populations. Various MBIs exist, though mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is the most extensively reviewed. Originally designed for patients with chronic medical and psychological conditions, it improves quality of life via focussed attention exercises, cognitive restructuring and adaptive learning techniques5. A 2020 systematic review of mindfulness – based stress reduction interventions on the psychological functioning of healthcare professionals showed that this particular method reduced anxiety, depression and stress and increased self-compassion6.

A 2021 systematic review on the impact of psychological Interventions with elements of mindfulness for physicians came to a similar conclusion: the vast majority of studies showed a positive impact on empathy, well-being, and reduction of burnout7. Similarly, a 2016 mixed method study showed that general practitioners who learned mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) techniques as a part of their regular CPD programme showed a significant decrease in depersonalisation and an increase in dedication and mindfulness skills compared with the control group8.

Interestingly, a decline in empathy and an increase in stress levels is not only experienced by established general practitioners but also by medical students and young doctors during their training. At the Charité – the medical faculty of the Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin - medical students can choose to take part in a voluntary course on stress reduction. Delivered over one semester, students are being taught methods of mindfulness and meditation with quantitative results showing a reduction in perceived stress and an increase in self-efficacy, mindfulness, self-reflection and empathy9, confirming previous results of similar interventions, including previously obtained long-term results of this course format showing effects on stress biomarkers10.

For those struggling to find the time to engage in MBI, the ubiquitousness of wearable technological devices such as smart watches and mobile phones can – rather counter-intuitively – help to take part in short activities helping to achieve emotional control in the middle of a busy day. An example for this is the ‘Mindfulness app’ on the Apple Watch (similar apps exist on Android-based devices). A small 2024 mixed method study invited participants to engage for 5 minutes daily with the application, trying to achieve 6 breaths per minute during usage. After two weeks the data showed this to result in a significant increase in participants’ coping skills and slight reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety11.

In these stressful days it feels important to identify strategies to the improve quality of life for the primary care workforce. For some, mindfulness-based interventions might be just the ticket, even when it’s only for 5 minutes a day.

References:

- Society of Occupational Medicine. What could make a difference to the mental health of UK doctors? A review of the research evidence. 2018.

- MDDUS. Compassion fatigue in healthcare professionals 2024.

- Colivicchi A. More than half of GPs reduced their sessions due to work-related stress. Pulse Today. 2025.

- Best, Ho. What’s it like to be a patient as a doctor. British Medical Journal 2024 Oct 11; q1486–6.

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Bantam Books, 2013

- Kriakous SA, Elliott KA, Lamers C, et al. The Effectiveness of mindfulness-based Stress Reduction on the Psychological Functioning of Healthcare professionals: a Systematic Review. Mindfulness. 2021 Sep 24; 12 (1): 1–28.

- Tement S, Ketiš ZK, Miroševič Š, et al. The Impact of Psychological Interventions with Elements of Mindfulness (PIM) on Empathy, Well-Being, and Reduction of Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Oct 25; 18 (21): 11181.

- Verweij H, Waumans RC, Smeijers D, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for GPs: results of a controlled mixed methods pilot study in Dutch primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2016 Jan 28; 66 (643): e99–105.

- Brinkhaus B, Stöckigt B, Witt CM, et al. Reducing stress, strengthening resilience and self-care in medical students through Mind-Body Medicine (MBM). 2025 Jan 1; 42 (1): Doc7–7.

- MacLaughlin BW, Wang D, Noone AM, et al. Stress Biomarkers in Medical Students Participating in a Mind Body Medicine Skills Program. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011; 2011: 1–8.

- Wright SL, Bach E, Bryson SP, et al. Using an App-Based Mindfulness Intervention: A Mixed Methods Approach. Cognitive and behavioral practice. 2024 Apr 1.

Written by Dr Dirk Pilat

Learning disability is the preferred UK term for individuals who have a ‘significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills’ and a ‘reduced ability to cope independently which starts before adulthood with lasting effects on development’1. Mencap estimates that there are approximately 1.5 million people with a learning disability in the UK (2.16% of adults and 2.5% of children)2, but is likely that the number of diagnoses recorded in health and welfare systems is significantly lower than the actual number of people living with learning disabilities3. This group represent a widely heterogenous group of patients with a broad spectrum of diagnoses and comorbidities, and will include some without a firm diagnosis to explain their learning disabilities.

The life expectancy of people with learning disabilities is reduced compared with the general population, with only 37% of affected adults living beyond 65 years of age, compared with 85% of the general population. These patients are at disproportionately higher risk of preventable deaths; this is often due to the underlying cause of mortality not being detected early and/or a delay in appropriate referral, and sub-standard management of conditions once they have been diagnosed. A recent review of deaths of people with learning disabilities identified 42% of deaths in this group as avoidable4.

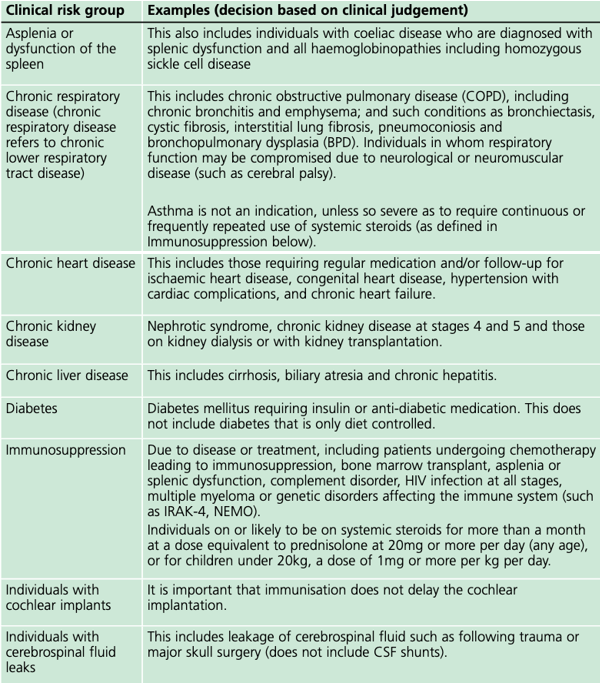

The second commonest cause of death in people with learning disabilities is respiratory (14.6%, compared with 16.7% who died of diseases of the circulatory system) with influenza and pneumonia being the most common infective causes. This clearly highlights the immense benefits this population would get from pneumococcal and influenza vaccination.

Evidence suggests that vaccine coverage rates are lower in those with a learning disability than in the general population; in children complete coverage rates were significantly lower for those with intellectual disabilities at ages nine months and three years5 and there is data to show that in the past, only half of adults receive a flu vaccination.

Pneumococcal vaccination is now part of the childhood vaccination regime and available for people in clinical risk groups as an additional vaccine depending on their age when they were diagnosed with a co-morbidity entitling them to the vaccination (see table).

In the risk group ‘chronic neurological disease’ (the category which includes those with learning disabilities), the mortality rate of influenza per 100,000 population is 37 times higher compared to those in no risk group. With annual influenza vaccination available for all affected since 2014, every general practice surgery has the chance to protect some of the most vulnerable people in their community, but this has not led to an appreciable increase in uptake.

To improve vaccine uptake amongst people with learning disabilities it is important to improve recording and coding (“coding is caring”!), as this will make this population more ‘visible’, facilitating invitation to annual learning disability health checks. Fear of medical interventions, including needles, may be a barrier to vaccination uptake in people with learning disabilities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NHS England developed a guide on how to increase uptake flu-vaccination for people with learning disabilities, and their key messages for GP-Surgeries were:

- GP surgeries should give a clear message that people with learning disabilities and their carers (family member and support workers) are entitled to a free flu vaccination.

- People on the learning disability register should have it recorded in their notes that they ‘need a flu vaccine’ – there is a specific Read / SNOMED code for this, or be called for vaccination using searches and reports on the clinical system.

- Practices can use this easy read flu invitation letter template for people with learning disabilities.

- Talk to people at their annual health check about why it is important that they have the flu vaccination.

- Put reasonable adjustments in place to help people with learning disabilities have their flu vaccination. This could be extra time, photo cards or an accompanying friend.

- The person seeing the patient may need to assess the patient’s capacity to decide to have the flu vaccine. If they do not have capacity for this decision, then this should not be a barrier to the flu vaccination being given; there would need to be a decision taken by the health professional that this is in their best interests.

- Consider the nasal spray flu vaccine as a reasonable adjustment. PHE guidance outlines the nasal spray can be used for people with a severe needle phobia. The nasal vaccine is not as effective as the injection, but some protection is better than none.

- Capitalise on attendance and offer the pneumococcal vaccine within the same appointment.7

In addition, people might benefit from scheduling their annual review during flu-vaccination season to try to immunise them opportunistically. The guide ‘Flu vaccinations: supporting people with learning disabilities’ from the UKHSA has a collection of resources on how to improve vaccine coverage for the target population.

Utilising these suggestions will increase vaccine coverage and improve health outcomes for one of the most vulnerable groups we look after in primary care.

References:

- Department of Health. Valuing People; A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century. 2001.

- Mencap. How common is learning disability in the UK?

- NHS England and NHS Improvement. Improving identification of people with a learning disability: guidance for general practice. 2019.

- LeDeR Autism and learning disability partnership, King's College London. Learning from Lives and Deaths - People with a learning disability and autistic people (LeDeR) report for 2022. 2023.

- Emerson E, Robertson J, Baines S, Hatton C. Vaccine Coverage among Children with and without Intellectual Disabilities in the UK: Cross Sectional Study. BMC Public Health. 2019 Jun 13; 19 (1).

- UK Health Security Agency. Pneumococcal: the green book, chapter 25

- Learning Disability & Autism Programme Team – NHS England & Improvement, South West. Communications toolkit: Increasing uptake of the flu vaccination for people with learning disabilities. 2020.

Written by Dr Emma Nash

Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as harmful or life threatening. Whilst unique to the individual, generally the experience of trauma can cause lasting adverse effects, limiting the ability to function and achieve mental, physical, social, emotional or spiritual well-being.1

Most of us are aware of post-traumatic stress disorder, resulting from an acute, significant traumatic event, but less aware of complex trauma. Complex trauma is exposure to a harmful or threatening experience over a longer period, where the individual cannot escape and is particularly linked to interpersonal relationships in childhood. The concept of complex trauma specifically relates to the effect the exposure has on the person rather than the event itself. Common themes include feelings of being unsafe, trapped, powerless, ashamed, humiliated, abandoned, invalidated, rejected or unsupported. It is the effects of these emotions and experiences that cause difficulties going forwards – trauma is not about what happened, it is about how the experience affects the individual’s future.

"Trauma is not what happens to you, but what happens inside you as a result of what happens to you" (Bessel Van der Kolk2).

The effects of trauma are multi-faceted and affect the way people manage perceptions and respond to the present. These effects are greatest in childhood trauma:

- Neurological: changes to brain structure and altered neurodevelopment.

- Biological: alterations to cortisol levels and the immune response.

- Social: interpersonal development is affected, with issues around trust and security.

- Psychological: impact on mood, anxiety, expression and regulation of distress.

Whilst trauma can occur at any age, childhood trauma is particularly important because of the impact of poor attachment on brain development and the development of resilience. A child develops a sense of safety through reliability. Unreliable, inappropriate or absent responses to need leads to altered neurodevelopment and an increased stress response. The consequence is negative for executive function: working memory (attention), inhibitory control (filtering thoughts/information to resist temptation/distraction and pause before action), and cognitive flexibility (apply different rules in different settings, think outside the box, problem solve).

The effects of trauma can look like other conditions – most commonly ADHD and personality disorder, but also autistic spectrum disorders, mood or anxiety disorders, and addictions.

|

Symptom overlap |

|

|

Complex trauma |

|

|

Personality disorder |

|

|

ADHD |

|

Trauma-informed practice is an approach to health and care interventions which is grounded in the understanding that trauma exposure can impact an individual’s neurological, biological, psychological and social development.1 Our experiences define our sense of self and our predictions about how people will behave towards us. Someone who has experienced trauma may have an uncertain sense of self, or struggle with interpersonal relationships as a result of inconsistent responses, lack of their needs being met, or other adverse responses to their emotional needs. As mentioned, it’s not the exact nature of the trauma that is important – at least at first – but to understand that it has happened and to recognise that it its impact. Neural network formation, and synaptic pruning (where unused connections are removed) are maximal in the first five years of life. This neuroplasticity means that the effects of trauma are easiest to reverse at this age, but harder as time goes on. By adulthood, significant investment in psychological interventions to understand the impact of trauma, and strategies to address it, is needed.

Trauma informed practice aims to create safety for patients by understanding the effects of trauma and its close links to health and behaviour. It is not about treating trauma – that is not the role of general practice – but about considering it. Applying a trauma-informed ‘lens’ can help reframe some of what you see, for example, ‘emotionally unstable’ may represent a heightened alert state, and ‘attention seeking’ may actually be ‘attachment needing’. Instead of asking ‘what is wrong with you?’, we should ask ‘what happened to you?’. It is important that we ask without re-traumatising, so don’t ask about details, you only need to know that something happened which was distressing and affected the way the patient sees themselves and their relationships with others. Applying a trauma-informed lens to patient behaviour can improve interpretation of underlying needs and emotions. The needs of an individual result in emotions, which manifest through behaviours. By applying a trauma-informed lens, the interpretation changes.

|

Behaviour |

à |

Meaning |

|

Not engaging |

Fearful |

|

|

Self-harm |

Ashamed |

|

|

Attention-seeking |

Connection-needing |

|

|

Relationship issues |

Let down by trusted people |

|

|

Impulsivity |

Hyper-reactive |

|

|

Emotionally volatile |

Hypervigilant |

|

|

Emptiness |

‘Freeze’ response |

|

|

Aggression |

Self-defence |

|

|

Dissociation |

Coping strategies |

|

|

Poor concentration |

Overwhelmed |

|

|

Substance misuse |

Seeking feeling |

Governmental guidance identifies six components to trauma-informed care1,3; fundamentally it is a thought process and attitude change. Try to have professional curiosity about the patient’s past and use that understanding to reframe their behaviour.

The key elements are:

- Safety: the clinician needs to create emotional and physical safety, enable people to ask for what they need, avoid re-traumatisation (e.g. invalidation) and consider the impact of their own actions.

- Trust: explain what you are doing and why, be reliable, set expectations and be transparent, make the person feel they are being listened to.

- Choice: share decision making and offer choice when available, recognise that they may feel a lack of control, and validate their concerns.

- Collaboration: utilise peer support, ask what they need, direct to appropriate support, and empower them where possible.

- Empowerment: validate their fears, concerns and opinions, listen to their wants and needs, support them to take action themselves, and recognise low self-worth.

- Cultural consideration: have self-awareness of cultural issues, bring cultural awareness and enquiries, and recognise the healing value of cultural connections.

There are multiple models for trauma recovery. Our role is in promoting safety and stability. This helps patients develop skills for managing distress and emotions, gives them control of their body and environment, encourages self-care and helps develop coping strategies.

Although there are no national guidelines published on best practice in managing complex trauma, trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy and trauma-focused eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) are most commonly used. Grounding techniques are a useful strategy to help manage distress. Treating comorbid mental health conditions and substance misuse in line with best practice also needs to take place – complex trauma should not be a barrier to accessing other help.

Key messages for general practice:

- Consider trauma.

- Recognise behaviours as an adaptive response to experience.

- Understand that relationships are key in recovery.

- It can be challenging.

References

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Working definition of trauma informed practice. 2022.

- Van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score. 2015. Penguin, USA.

- NHS Education for Scotland. Transforming Psychological Trauma: A Knowledge and Skills Framework for the Scottish Workforce. 2017.

- Herman, J.L. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books. 1992

Resources

- Mind. Complex PTSD.

- Penna, S. How to support children that have experienced household psychological or emotional abuse. Mental Health Today. 2019.

- PTSD UK. Complex PTSD.

- PTSD UK. Grounding techniques for PTSD and C-PTSD.

- Trauma Recovery UK

- UK Trauma Council

- University of Sydney. Grounding techniques self-help resource.

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Shared care is defined by NHS England (NHSE) as ‘a particular form of the transfer of clinical responsibility from a hospital or specialist service to general practice in which prescribing by the GP, or other primary care prescriber, is supported by a shared care agreement’1. Shared care drugs tend to be those which we would not start in primary care, but where ongoing prescription by the GP is felt to be safe. This makes life easier for the patient, who can get all of their medications in the same place but moves the medicolegal prescribing responsibility from the specialist to the GP. In order for this to be safe, there has to be a shared care agreement in place, with good communication between the specialist and the GP (in both directions).

Most of the key references in this blog are from NHSE and therefore pertain only to England – shared care issues in the devolved nations of the UK are generally agreed by individual health boards (Scotland/Wales) or health and social care trusts (NI) and so equivalent information should be sought from them.

The NHSE list of shared care drugs2 includes disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate and leflunomide, lithium, medications to treat ADHD in adults, sodium valproate for patients of child-bearing potential and ciclosporin for patients using it for a non-transplant indication. The NHSE list is not exhaustive and some ICBs have shared care protocols for medications which aren’t on the NHSE list, including testosterone as part of HRT3, denosumab for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures4, and cinacalcet for primary hyperparathyroidism5. The GP responsibilities will vary by drug; examples include 3-6 monthly height, weight, blood pressure and pulse for children on ADHD medication and monitoring bloods, usually every three months, for DMARDs. Some of these bloods can pick up potentially serious complications including hepatotoxicity, so it’s important that there is a clear and rapid line of communication for expert advice in the event of an abnormal test result.

Shared care can only start when the following criteria are met1:

- The patient’s clinical condition is stable.

- The GP has freely agreed to take part in shared care; if the GP feels that it isn’t safe or adequately resourced, prescribing stays with the specialist on a long-term basis.

- There is an agreed, written, shared care agreement, which states how often the patient will be reviewed and gives a ‘route of return’ if their condition changes, allowing specialist review without the need for a new referral.

- The specialist has provided enough medication to cover the transition period.

It follows from the above, that all specialist clinics who manage patients on shared care medications need to be able to prescribe long-term, as there has to be an alternative for those whose GP doesn’t feel that the proposed shared care is safe or adequately resourced. NHSE1 are clear that the specialist, patient/carers and GP all have to give ‘willing and informed consent’ before shared care can take place, which implies that a referral form cannot state that an agreement to shared care is a pre-requisite of the referral being accepted, because consent given at that point cannot be fully informed. The idea of informed consent would also suggest that shared care agreements should not contain words to the effect that if no response is received from the GP within a certain time period, the acceptance of shared care will be assumed. Good communication is a GMC obligation6 which applies to both the specialist and GP, so it would be reasonable to assume that a request for shared care would meet with a prompt reply from the GP, whether this was an acceptance of the shared care, a rejection, or a request for more information.

NHSE guidance on shared care does not explicitly state that the patient can never be discharged from their specialist team. However, the specialist obligations towards a patient for whom the GP is sharing care are harder to meet if the patient is discharged. These include the availability of care and advice without needing a new referral1 (often impossible in the NHS outside of a defined period of patient-initiated follow-up7), and NICE8 or other guideline requirements which mandate regular specialist review for some shared care medications. Multiple ICB shared care protocols9,10 state that the patient should usually stay under the care of both specialist and GP and individual practice should always keep patient safety at the forefront of their minds when deciding whether to share care with a specialist team who propose to discharge the patient.

References

1. NHSE. Responsibility for prescribing between Primary & Secondary/Tertiary Care. March 2018.2. NHSE. Shared care protocols. January 2022.

3. Bath and North East Somerset Swindon and Wiltshire Together. Shared care agreement. Off-label topical testosterone in adult women on HRT. Dec 2023.

4. Derbyshire joint area prescribing committee. Shared care agreement - denosumab 60mg for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in men and post-menopausal women aged 18 and over. June 2022.

5. Hampshire and Isle of Wight ICB. Cinacalcet for patients within Adult Services (Primary hyperparathyroidism and other indications). Share Care Guidelines. Oct 2024.

6. GMC. Good Medical Practice. January 2024.

7. NHSE. Implementing patient initiated follow-up: guidance for local health and care systems. May 2022.

8. NICE. NG87. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. Sept 2019.

9. Hertfordshire and West Essex ICB. A frequently asked questions document: Shared care for medicines and NHS shared care and specialist guided prescribing service specification. Oct 2024.

10. Nottinghamshire APC. Frequently asked Questions about Shared Care for Patients and Carers. March 2022.

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Stopping smoking is one of the most significant things that a person can do to improve their health. It is the second most cost-effective measure in COPD management (behind flu vaccination and ahead of all pharmaceuticals)1 and is associated with later mortality, whatever the age of quitting. It is however not an easy thing to do, with multiple studies showing that most people will relapse after their first quit event3,4,5 – encouragement to try again is therefore vital.

Smoking cessation is more likely to be successful with a combination of support and pharmacotherapy than when tried alone, or with just one of these modalities6. Our role as GPs is not usually to provide this support, but to signpost patients to stop smoking clinics and potentially to prescribe on the clinic’s behalf (depending on local commissioning arrangements). To do this effectively and safely, it helps to understand the principles of very brief advice (VBA), the basic biochemistry of smoking addiction and the pharmacology of the drugs currently available.

VBA is a NICE approved7 30-second intervention which can be delivered in a normal GP appointment; there is evidence that it is acceptable to patients and can contribute to successful smoking cessation8,9. VBA consists of three ‘As’ – ask, advise, act. Ask the patient if they smoke. Advise them how to stop smoking (by explaining that they are much more likely to succeed with support and pharmacotherapy than on their own) and advise them as to how they can access this support. This might be via referral, or by giving the patient details for the local self-referral scheme.

After attendance at a smoking cessation clinic, you may be asked to prescribe nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or one of the three currently available drugs – varenicline, cytisinicline and bupropion7. These all act in different ways on the addiction mechanisms which keep people smoking. When a smoker inhales nicotine there is a rapid increase in dopamine10, causing an immediate sensation of pleasure; as nicotine and dopamine levels fall, the desire for the next cigarette increases. With long-term smoking, nicotine receptors are upregulated in both number and sensitivity11, causing dependence; down-regulation after quitting takes 6-12 weeks12. The table below gives brief information about what we can prescribe; more detail is available in our eLearning module, Essentials of Smoking Cessation, which also discusses e-cigarettes.

| Smoking cessation drug | Mechanism of action | Use in pregnancy, breastfeeding and under 18s | Other information (non-exhaustive list; consult BNF before prescribing) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRT | Stimulates nicotine receptors to release dopamine, reducing withdrawal symptoms13. | Yes (from age 12). |

|

| Bupropion | Increases dopamine levels by reducing dopamine reuptake, reducing withdrawal symptoms14. | No |

|

| Varenicline | Stimulates nicotine receptors to release dopamine and blocks the rapid dopamine increase from nicotine16,18,19. | No |

|

| Cytisinicline | Stimulates nicotine receptors to release dopamine and blocks the rapid dopamine increase from nicotine16,18,19. | No |

|

References

- Murphy PB, Brueggenjuergen B, Reinhold T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of home non-invasive ventilation in patients with persistent hypercapnia after an acute exacerbation of COPD in the UK. Thorax 2023; 78: 523-525.

- Cho ER, Brill IK, Gram IT, et al. Smoking Cessation and Short- and Longer-Term Mortality. NEJM Evid. 2024 Mar; 3 (3): EVIDoa2300272.

- Gorniak B, Yong HH, Borland R et al. Do post-quitting experiences predict smoking relapse among former smokers in Australia and the United Kingdom? Findings from the International Tobacco Control Surveys. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022 May; 41(4): 883-889.

- Lee SE, Kim CW, Im HB, et al. Patterns and predictors of smoking relapse among inpatient smoking intervention participants: a 1-year follow-up study in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2021; 43: e2021043.

- Feuer Z, Michael J, Morton E, et al. Systematic review of smoking relapse rates among cancer survivors who quit at the time of cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022 Oct; 80: 102237.

- Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 24; 3(3): CD008286.

- NICE. NG209. Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence. Feb 2025.

- Cheng CCW, He WJA, Gouda H, et al. Effectiveness of Very Brief Advice on Tobacco Cessation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2024 Jul; 39(9): 1721-1734.

- Papadakis S, Anastasaki M, Papadakaki M, et al. 'Very brief advice' (VBA) on smoking in family practice: a qualitative evaluation of the tobacco user's perspective. BMC Fam Pract. 2020 Jun 24; 21(1): 121.

- Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009; 49: 57-71.

- Govind AP, Vezina P, Green WN. Nicotine-induced upregulation of nicotinic receptors: underlying mechanisms and relevance to nicotine addiction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009 Oct 1; 78(7): 756-65.

- Cosgrove KP, Batis J, Bois F, et al. beta2-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability during acute and prolonged abstinence from tobacco smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Jun; 66(6): 666-76.

- Molyneux A. Nicotine replacement therapy. BMJ. 2004 Feb 21; 328(7437): 454-6.

- Warner C, Shoaib M. How does bupropion work as a smoking cessation aid? Addict Biol. 2005 Sep; 10(3): 219-31.

- Bupropion SPC. July 2024.

- Singh D, Saadabadi A. Varenicline. [Updated 2024 Oct 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. The prescribing of varenicline and vaping (electronic cigarettes) to patients with severe mental illness. Dec 2018.

- National centre for smoking cessation and training. Cytisine. 2024.

- Nides M, Rigotti NA, Benowitz N, et al. A Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2b Trial of Cytisinicline in Adult Smokers (The ORCA-1 Trial). Nicotine Tob Res. 2021 Aug 29; 23(10): 1656-1663.

- NHS Wales. Cytisinicline. July 2024.

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. Medicines Advice.

- Stop Smoking NI.

- National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT). 30 Seconds to change a life.