Royal College of General Practitioners - Online Learning Environment

Site blog

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Written by Dr Toni Hazell

Menopause is defined as a biological stage in a woman’s life when menstruation stops permanently, due to the loss of ovarian follicular activity. It is a retrospective diagnosis, made 12 months after the last period, which often follows several years of perimenopause in which periods can be irregular and menopausal symptoms may be felt. The average age of the menopause in the UK is 51. An early menopause is one that happens before 45. Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is defined as the transient or permanent loss of ovarian function below the age of 401. Care for women with POI should be holistic – as well as the risks to physical health, POI can be very distressing, particularly for those women who do not feel that they have completed their family.

A woman with POI may have an absolutely reduced number of ovarian follicles, or there may be remaining follicles which are not functioning properly. 90% of POI is idiopathic, but the following causes of a reduction or poor function of the follicles may be found in up to 10% of women2:

- Chromosomal disorders (e.g. Fragile X and Turner syndrome)

- Autoimmune disease (e.g. thyroiditis and Addison’s)

- Iatrogenic (e.g. due to the use of chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy or surgical after oophorectomy)

- Metabolic disorders (e.g. galactosaemia)

- Toxins such as cigarette smoke and some chemicals and pesticides can speed up follicle depletion

- Infection (e.g. mumps, TB and malaria – this is rare).

POI should be suspected in women who are under than 40 who have at least four months of amenorrhoea, with an estimated FSH level of more than 30 IU/L on two blood samples taken 4 – 6 weeks apart1,2,3. If the diagnosis is in doubt, then a referral should be done4. Referral might be to a specialist menopause clinic, to endocrinology or to gynaecology, depending on your specific concerns and what pathways you have available locally. A full history should be taken, including:

- a review of menopausal symptoms

- other possible causes (including pregnancy)

- lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, exercise, nutrition)

- the need for contraception (women with POI still have a small risk of ovulation)

- smear status

- family history of POI, venous thromboembolism or breast cancer

- the woman’s thoughts about HRT use

- any co-morbidities which might be relevant when considering HRT use

- osteoporosis risk – consider a baseline assessment of bone mineral density, with a repeat 2-3 years after diagnosis3.

Those who have worked in primary care for decades will be aware of the changing demand for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) over the years, with a significant decline in the early 2000s5, associated with concerns about cardiovascular risk and breast cancer, often based on studies looking at different populations from those who are prescribed HRT in the UK. This has been reversed in the last few years, with a 35% increase in HRT items prescribed from 2020/21 to 2021/226. It is vital that healthcare professionals understand the key difference between prescribing HRT for women who go through their menopause at a normal age, and those with POI, as the risk/benefit analysis is completely different. For women with POI, HRT is merely replacing the hormones that an average woman would have had naturally and reducing the excess risk of osteoporosis that comes with POI. For the vast majority there appears to be no excess risk of breast cancer arising from the use of HRT up to the age of 503. Both NICE4 and the British Menopause Society3 (BMS) are clear that this cohort of women should be offered HRT unless there is a clear absolute or relative contraindication, the main one being a history of a hormone sensitive cancer such as breast cancer. All the data that we have suggests that transdermal oestrogen does not increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in women who have their menopause at a normal age3,4 – the BMS acknowledges the limited data in women with POI but says that the transdermal route should be considered in women with POI who are at an increased risk of VTE, for example due to obesity. Transdermal oestrogen, when used with micronised progesterone, is also ‘unlikely to significantly increase VTE risk above the individual’s intrinsic risk’7 for those who have a personal or family history of VTE.

The decision as to whether to refer a woman with POI to a specialist menopause clinic will depend on several factors. These may include the level of suspicion of an underlying cause, the confidence of the GP to manage POI, the woman’s desire for ongoing fertility, a need for specialist psychological input and any individual risk factors for HRT. For women with a history of a hormone sensitive cancer, a referral to discuss the risks and benefits of HRT would be sensible, and this discussion might usefully include her oncologist.

Women who go through their menopause at a normal age are advised to use contraception for one year after their last period (if that happens over the age of 50), or two years if their last period is under the age of 50. Women with POI have a higher risk of spontaneous ovulation and conception and have around a 5 – 10% change of spontaneous natural conception3. Contraception is therefore advised if they do not want to become pregnant and some will prefer to use combined hormonal contraception (CHC) instead of HRT – either are suitable options for oestrogen replacement (assuming no contraindications to combined hormonal contraception), although HRT may be more beneficial for bone health and cardiovascular risk3. They should continue to have smear tests at the normal frequency for their age. If a woman has no need for contraception (e.g. post sterilisation) and has no other licensed indications (e.g. menstrual symptoms) and is using CHC because she prefers it to HRT, then this will be unlicensed.

A diagnosis of POI can have physical, social, and

psychological impacts on a woman and her family so holistic care is important.

Signposting to a charity such as The Daisy Network8 and to reliable

sources of information such as the Women’s Health Concern9, Rock My

Menopause10, the RCOG menopause hub11, and articles on

the website Patient12 may help her to feel more in control. GPs who

wish to learn more about menopause might want to start with the RCGP course on

the subject, consisting of a half-hour eLearning module, a short screencast and

a podcast13. Access Menopause eLearning course via the following link https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/info.php?id=663

Declaration of interests – Dr. Hazell does both paid and

unpaid work for the PCWHF, who host Rock My Menopause, and also works for the

website Patient.

References (all viewed 26.5.23)

1) NICE CKS. Menopause. Last updated September 2022. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/menopause/

2) Daisy network. What is POI. https://www.daisynetwork.org/about-poi/what-is-poi/

3) British Menopause Society. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. April 2020. https://thebms.org.uk/publications/consensus-statements/premature-ovarian-insufficiency/

4) NICE. NG23. Menopause: diagnosis and management. Last updated December 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23

5) Cagnacci A, Venier M. The Controversial History of Hormone Replacement Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Sep 18;55(9):602

6) NHSBSA Statistics and Data Science. Hormone replacement therapy – England. October 2022. https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/hormone-replacement-therapy-england/hormone-replacement-therapy-england-april-2015-june-2022

7) Hamoda H, Panay N, Pedder H et al. The British Menopause Society & Women's Health Concern 2020 recommendations on hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women. Post Reprod Health. 2020 Dec;26(4):181-209

8) The Daisy Network. https://www.daisynetwork.org/

9) Women’s Health Concern. https://www.womens-health-concern.org/

10) Rock My Menopause. Premature ovarian insufficiency factsheet. https://rockmymenopause.com/portfolio-item/premature-ovarian-insufficiency

11) RCOG. Menopause and later life. https://www.rcog.org.uk/for-the-public/menopause-and-later-life/

12) Patient. What it’s like to go through early menopause. Last updated June 2019. https://patient.info/news-and-features/what-its-like-to-go-through-early-menopause

13) RCGP eLearning. Menopause. September 2022. https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/view.php?id=663

14) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What causes POI? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/poi/conditioninfo/causes

You might have read recently in the daily and medical press that there has been an outbreak of diphtheria among asylum seekers in England. Even though refugees are often young, physically fit males, they can have complex health needs after their long journeys, such as untreated communicable diseases. Since June 2022 there has been an increase in diphtheria cases, and as of December 2022 62 cases of diphtheria had been confirmed, with half of the cases being cutaneous. Before mass vaccination, diphtheria was once one of the most feared childhood diseases in the UK, with more than 61,000 cases and 3,283 deaths in 1940.

Figure 1 Corynebacteriæ diphtheriæ

Source: CDC

This image is in the public domain and thus free of any copyright restrictions. Use of this image does not constitute this blog’s endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Diphtheria is caused by the non-sporing, non-encapsulated, and non-motile Gram positive bacillus Corynebacteriæ diphtheriæ and Corynebacteriæ ulcerans. Respiratory diphtheria presents with a pharyngitis that often will be associated with a visible greyish membrane and enlarged anterior cervical lymph nodes with perinodal swelling, causing the classic bullneck appearance. Laryngeal diphtheria can be associated with progressive hoarseness and stridor, while nasal diphtheria can present with uni- or bilateral discharge and crustiness. As diphtheria has become increasingly rare in the United Kingdom, thanks to a successful immunisation campaign, it’s not always instantly recognisable for clinicians.

Figure 2 Bullneck appearance

Figure 2 Bullneck appearance

Source: CDC

This image is in the public domain and thus free of any copyright restrictions. Use of this image does not constitute this blog’s endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The incubation period for diphtheria is usually 2 to 5 days but may be longer. The commonest mode of transmission of C. diphtheriæ is via droplet spread from a person with respiratory diphtheria; prolonged close contact is usually required for spread.

Cutaneous diphtheria usually starts as a vesicular rash and then forms one or more clearly demarcated ulcer that can be covered in a blueish-grey membrane. Patients may have both cutaneous and respiratory disease.

Figure 4 cutaneous diphtheria

Source: CDC

This image is in the public domain and thus free of any copyright restrictions. Use of this image does not constitute this blog’s endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Figure 3 respiratory diphtheria by User: Dileepunnikri is licenced under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Swabs should be collected from patients and sent to a local diagnostic laboratory with appropriate clinical details.

All suspected cases have to be notified to the UK Health Security Agency. Patients might be referred to the local specialist infectious disease team for face-to-face assessment and review. Treatment options include diphtheria anti-toxin intravenously and macrolide antibiotics.

References

Knights, F; Munir, S (2022). Initial health assessments for newly arrived migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. BMJ 2022;377:e068821 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068821

British Medical Association (2022). Unique health challenges for refugees and asylum seekers. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/ethics/refugees-overseas-visitors-and-vulnerable-migrants/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-patient-health-toolkit/unique-health-challenges-for-refugees-and-asylum-seekers (Accessed 19.01.2023)

UK Health Security Agency (2022): Infectious diseases in asylum seekers: actions for health professionals. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/infectious-diseases-in-asylum-seekers-actions-for-health-professionals (Accessed 19.01.2023)

UK Health Security Agency (2022): Public health control and management of diphtheria in England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1117027/diphtheria-guidelines-2022_v17_111122.pdf (Accessed 19.01.2023)

It is now over 40 years ago since a rare lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii was noticed in five young, previously healthy men who lived in Los Angeles1. The article describing this cluster or cases was the first hint of a global epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which at the time led inexorably to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and almost certain death.

Fast forward to 2022 and HIV has become a treatable chronic disease – those who are adherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART) with an undetectable viral load can expect a normal or near-normal life span2 and no longer have to worry about passing the virus to a sexual partner, as this is impossible for those on effective treatment3.

The most important factor in reducing morbidity and mortality is early diagnosis and early initiation of ART. Progress of the virus is measured by monitoring the viral load and CD4 count (a type of T lymphocytes). If HIV is diagnosed late (when the CD4 count has dropped below 350 cells/mm3), there is a ten-fold increase in risk of the patient dying in the year after diagnosis4,5 and if this doesn’t happen, they still have a likely ten-year reduction in life expectancy2. It is estimated that 6,600 people in England have undiagnosed HIV, making up approximately 6% of the total population of people with HIV in England6. This group will have a poor prognosis if they remain undiagnosed, and risk unknowingly passing the virus to their sexual partners.

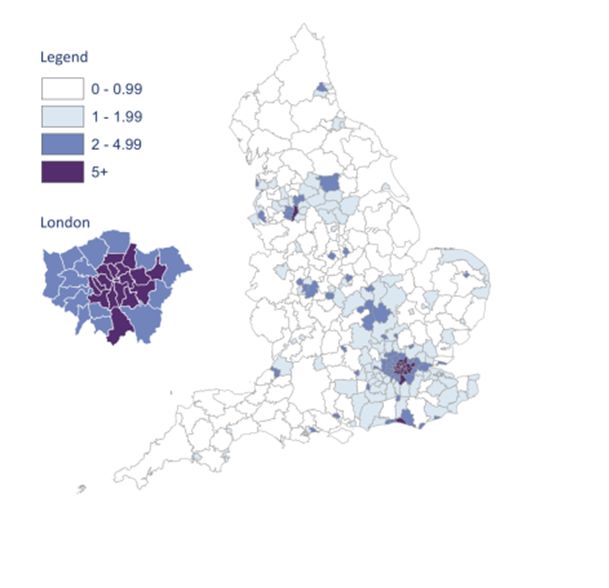

NICE guidance advises that we offer and recommend HIV testing based on local prevalence, which can be seen on this map of diagnosed HIV prevalence per 1,000 population aged 15 – 59 years in England in 2015. There are hotspots of high prevalence (2-5 cases per 1,000) and extremely high prevalence (>5 cases per 1,000) in various cities including London, Brighton and Manchester – healthcare professionals in these areas should be aware of the recommendation to offer routine HIV tests as laid out in the table below7, which also covers the clinical situations in which any healthcare professional should offer a test, regardless of local prevalence.

Map from HIV in the UK 2016 Report, Public Health England8

Image used under the Open Government Licence v3.0

|

Prevalence level |

When to offer a test |

|

High |

|

|

Extremely high |

|

|

Any prevalence |

|

In primary care we should be aware that HIV may present at seroconversion, or later as the CD4 count drops and symptoms of immunodeficiency start to emerge.

Seroconversion occurs between 10 days and six weeks after infection with HIV and may be very mild. It is difficult to diagnose as clinical features can be non-specific, including a fever, sore throat, malaise and arthralgia. A maculopapular rash, particularly in combination with a fever, should alert us to the possibility of seroconversion2. Traditionally we have considered there to be a 12 week ‘window period’ for HIV testing – the time in which a person may have contracted HIV, but still have a negative test as they have not yet made enough antibodies for the test to be positive. Many labs now use combined antibody/antigen tests which shorten the window period, but unless you are familiar with the tests used locally, it is safest to advise that anyone who may be in the early stages of HIV repeats their test at least 12 weeks after any encounter where they think they may have caught the virus.

Later symptoms are listed in the British HIV Association list of ‘clinical indicator diseases’, which are defined by the fact that patients with these conditions have at least a 1 in 1000 likelihood of having undiagnosed HIV9. They include diagnoses and incidental findings which are commonly seen in general practice, such as unexplained fever, lymphadenopathy, chronic diarrhoea or weight loss, unexplained low white cell count or platelet count and any cervical dysplasia or community acquired pneumonia. We should also consider testing for various skin conditions, including seborrhoeic dermatitis, shingles and severe psoriasis, and for those with lung cancer or lymphoma.

It is not all that often that we can point to a specific consultation in primary care and say “I saved a life today”. Picking up a case of HIV and getting a patient on to antiretrovirals is a truly life-saving measure, for which an increase in testing is vital.

References (all accessed 9.10.22)

1. HIV.gov. A timeline of HIV and AIDS. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline#year-1981

2. NICE CKS. HIV infection and AIDS. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hiv-infection-aids/

3. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. HIV Undetectable=untransmissible, or Treatment as Prevention. 2019. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/treatment-prevention

4. The Lancet HIV. Time to tackle late diagnosis. Lancet HIV. 2022 Mar;9(3): e139

5. UK Health Security Agency. Leaving it late: why are people still dying from HIV in the UK? 2014.

6. Public Health England. Trends in HIV testing, new diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2019. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/959330/hpr2020_hiv19.pdf

7. NICE NG60. HIV testing: increasing update among people who may have undiagnosed HIV. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng60/chapter/Recommendations#offering-and-recommending-hiv-testing-in-different-settings

8. Public Health England. HIV in the UK 2016 Report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/602942/HIV_in_the_UK_report.pdf

9. British HIV Association. British HIV Association/British Association for Sexual Health and HIV/British Infection Association Adult HIV Testing Guidelines 2020. 2020. Appendix 1. https://www.bhiva.org/file/5f68c0dd7aefb/HIV-testing-guidelines-2020.pdf

Introduction

Constipation is a common, frequently encountered gastrointestinal disorder affecting approximately one third of adults 60 years and older, with over half of nursing home residents affected. Constipation can have significant consequences: in susceptible and frail older people, excessive straining can trigger a syncopal episode and coronary or cerebral ischaemia. In severe cases, constipation can lead to anorexia, nausea and pain and ultimately can cause a stercoral ulcer, leading to perforation and death. Stercoral ulcers are due to hard, impacted faeces causing pressure necrosis of the distal colon, leading to ulceration and subsequent perforation of the intestinal wall.

Constipation often causes a reduction in the quality of life, with general health, vitality, social functioning and mental health all affected. Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age, inactivity, low calorie intake, a low-fibre diet, polypharmacy, and low income. The incidence of constipation is three times higher in women, and women are twice as likely as men to see their primary care team for constipation.

Symptoms

Patients usually complain of ‘straining’ when opening their bowels, difficulty passing stools, incomplete evacuation or both. This is often associated with hard stools, abdominal bloating pain and distention. The stool frequency may be normal.

Primary constipation

Primary constipation includes the subtypes of normal transit, slow transit and disorders of defaecation, all of unknown causes. Histology of the colon of older adults shows more tightly packed collagen fibres and a reduced number of myenteric neurons, but these changes are not considered to be major contributors to the development of constipation.

Secondary constipation

Secondary causes of constipation include medication use, chronic disease processes and psychosocial issues. Opioids, calcium channel blockers, oral iron supplements, antacids and anticholinergics are common causes for medication-induced constipation, while hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, Parkinson’s disease and colorectal carcinoma can all cause secondary constipation.

Assessment

Patients should always be assessed for red flags that might indicate an underlying malignancy, such as:

· persistent unexplained change in bowel habits

· palpable mass in the lower right abdomen or the pelvis

· persistent rectal bleeding without anal symptoms

· narrowing of stool calibre

· family history of colon cancer, or inflammatory bowel disease

· unexplained weight loss, iron deficiency anaemia, fever, or nocturnal symptoms

· severe, persistent constipation that is unresponsive to treatment.

NICE guidance NG12 gives primary care practitioners a clear framework when to refer a patient with suspected colorectal cancer on a two week wait (2ww) suspected cancer pathway referral.

When evaluating an older individual with constipation, taking a thorough drug and medical history and performing a physical examination are important. Abdominal examination might reveal abnormal bowel sounds, significant weight loss, cachexia, masses and/or sigmoid or colonic loading. When planning a rectal examination, the patient should be informed about its diagnostic importance and the fact that it might be uncomfortable. A chaperone should always be offered and consent documented. Examination of the anus might reveal abnormalities such as proctitis, haemorrhoids, prolapse, fissures or rectal cancer, while further up in the ampulla a rectal-digital examination can detect faecal impaction, masses, and gives the examiner the chance to evaluate anal tone.

Management

Non-pharmacological treatment is often the first step to help patients in the management of their complaint with adaptation of the patients’ medication a start to reduce symptoms.

Endocrinological/psychological/neurological causes of secondary constipation will need investigation and appropriate management. It might be worth discussing with the patient that there is no physiological necessity to have a daily bowel motion: a discussion around simple lifestyle changes might improve their perception of bowel regularity and a diary reporting on stool pattern and consistency may be helpful as well. The optimal time to have a bowel movement is often after waking and/or after meals, when the colon’s motor activity is particularly pronounced. A gradual increase in the intake of fluids and fibre should be suggested, but we should be careful in patients with cardiorenal issues not to cause overloading. A prospective study from Japan found that placing the patient’s feet on a small foot stool in front of the toilet, in conjunction with the upper body bent forward, improved anal pressure and reduced time of evacuation. Patients in care homes should be given adequate time and privacy for their bowel movements and should avoid bed pans.

Most patients will, at one stage, require a laxative to alleviate their symptoms when lifestyle interventions are ineffective: in patients with short-duration constipation a bulk forming laxative such as ispaghula husk should be initiated. If these are not helpful, an osmotic laxative such as macrogol should be next.

In chronic constipation, a bulk forming laxative should be initiated, with adequate hydration ensured (low fluid intake with bulk forming laxatives can cause impaction). If defaecation continues to be unsatisfactory, an osmotic laxative should be the next choice, with the addition of a stimulant laxative such as bisacodyl if the patient doesn’t improve. Once regular bowel movements occur, the laxatives can be slowly withdrawn.

If there is no response to the maximum tolerated dose of second line laxatives, refer to the local GI or older people’s outpatient team, or ask for guidance via the local advice and guidance process.

If the patient presents with faecal impaction, the appropriate escalating dose of a macrogol should be considered. In those with soft stools, or with hard stools after a few days’ treatment with a macrogol, an oral stimulant laxative should be started or added to the previous treatment. If the response continues to be underwhelming, rectal administration of bisacodyl (for soft stools) or glycerol (for hard stools) can be considered.

If there is still no response, a sodium acid phosphate with sodium phosphate enema may have to be considered. For hard stools, an overnight arachis oil enema, followed by a sodium acid phosphate with sodium phosphate enema the next morning might prove effective.

In patients with opioid-induced constipation, an osmotic laxative (or docusate sodium to soften the stools) and a stimulant laxative is recommended. Bulk-forming laxatives should be avoided.

If the patient’s presentation is getting worse or there is no response, then consult with one of your colleagues from gastroenterology. Further input from these teams might be needed for additional pharmacotherapy, endoscopy, anorectal manometry or other secondary/tertiary care investigations.

References:

Arco, S; Saldaña, E et al (2021). Functional Constipation in Older Adults: Prevalence, Clinical Symptoms and Subtypes, Association with Frailty, and Impact on Quality of Life. Gerontology DOI: 10.1159/000517212

British National Formulary: Constipation https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/constipation/ accessed 14/7/2022

Gandell, D; Straus, SE et al (2013). Treatment of constipation in older people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, May 14, 185(8) DOI:10.1503/cmaj.120819

De Giorgio, R; Ruggeri, E et al (2015). Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterology 15:130 DOI 10.1186/s12876-015-0366-3

Gough, AE; Donovan, MN et al (2016). Perforated Stercoral Ulcer: A 10-year experience. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Vol 64, No 4

Heidelbaugh, J; Martinez de Andino, N et al (2021). Diagnosing Constipation Spectrum Disorders in a Primary Care Setting. Journal of Clinical Medicine. (10) 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10051092

Hull and East Riding Prescribing Committee (2019). Management of Constipation in Adults. https://www.hey.nhs.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/GUIDELINE-Constipation-guidelines-updated-may-19.pdf accessed 14/7/2022

Jamshed, N; Lee, Z; Olden, KW (2011). Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults. American Family Physician. 84(3):299-306

Mounsey, A; Raleigh, M et al (2015). Management of Constipation in Older Adults. American Family Physician Volume 92, Number 6

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021). NG12 Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/chapter/Recommendations-organised-by-site-of-cancer#lower-gastrointestinal-tract-cancers accessed 14/7/2022

Rome Foundation (2016) Appendix A: Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for FGIDs. https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/ accessed 14/7/2022

Schuster, BG; Kosar, L et al (2015). Constipation in older adults; Stepwise approach to keep things moving. Canadian Family Physician 61: February

Takano, S; Nakashma, M et al (2018). Influence of foot stool on defecation: a prospective study. Pelviperineology 2018; 37: 101-103

Villanueva Herrero JA, Abdussalam, A et al (2022). Rectal Exam. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30726041/

July 2022 will see Integrated Care Systems (ICS) become statutory in England. Partnerships between NHS service providers, commissioners, local authorities, and other organisations will be responsible for planning, co-ordinating and commissioning health and care services that meet the needs of each geographically defined community. Included within each community will be a relatively small number of people who are in contact with the criminal justice system, some of whom will go in and out of prison more than once. It is recognised that this cohort, while heterogeneous, often has highly complex needs and frequently experiences poorer than average health access, experience, and outcomes.

July 2022 will see Integrated Care Systems (ICS) become statutory in England. Partnerships between NHS service providers, commissioners, local authorities, and other organisations will be responsible for planning, co-ordinating and commissioning health and care services that meet the needs of each geographically defined community. Included within each community will be a relatively small number of people who are in contact with the criminal justice system, some of whom will go in and out of prison more than once. It is recognised that this cohort, while heterogeneous, often has highly complex needs and frequently experiences poorer than average health access, experience, and outcomes.

Whilst in prison, men and women from this cohort will be temporarily ‘hidden’ from their community ICS commissioning landscape (commissioning of prison healthcare takes place separately, by NHS England and NHS Improvement health justice commissioners in England, Health Boards in Wales and Scotland and the South East Trust in Northern Ireland), and may be in secure settings distant from the locality to which they will return. It is essential that, as integrated care systems are launched, there will be representation and acknowledgement of the needs of these patients to avoid compounding the health inequalities gap. NHS England and NHS Improvement have introduced Core20PLUS5, an approach to address health inequalities at national and system levels. It identifies the most deprived 20% of the population, plus those not captured in the 20% who experience poorer than average health and recognises five ‘focus’ clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement. Those in touch with the criminal justice system are considered an ‘inclusion’ group in the PLUS cohort. This strategy aims to ensure that health and care needs are met in people in contact with the criminal justice system.

Once in prison, people are not able to choose where or from whom they receive their healthcare provision. Healthcare services in secure environments need to be configured to take account of the particular needs of the population they are serving, for example with regard to the increased prevalence of mental ill health, substance misuse and communicable diseases, whilst also acknowledging the distinctive settings in which the care needs to be delivered.

Healthcare practitioners have a duty of care to their patients, and in the secure setting this duty must be delivered in the context of the physical environment and lifestyle constraints prison brings, whilst utilising the assistance of the staff providing the security for the establishment. As a result, healthcare delivery in the secure setting requires continual collaboration and partnership working between prison and healthcare staff to deliver the most beneficial services.

A healthcare worker in a prison has a unique opportunity to address the needs of some of society’s most vulnerable people and this must be done without prejudice. This means that the nature of someone’s offence, or the reason for their detention, should not alter how patients are cared for.

Particular risks to patient safety, engagement and health equity occur at transition points, as people move into and out of prison, or are moved from one prison to another. NHS RECONNECT schemes have been set up to bridge the gap for patients being released from prison. They aim to facilitate continuity of care by ensuring that health information is shared, and connections are built with community health care practitioners before a patient leaves prison. The success of pre-release healthcare arrangements requires careful coordination with the probation service and the local authority to ensure that suitable housing is identified within the locality that community healthcare provision has been arranged.

In 1996, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons, Sir David Ramsbotham, published his paper “Patient or Prisoner?” in which his terms of reference were: ‘to consider health care arrangements in Prison Service establishments in England and Wales with a view to ensuring that prisoners are given access to the same quality and range of health care services as the general public receives from the National Health Service’. This paper introduced the concept of ‘equivalence’ of care and set the scene for what continues to be an evolving area of prison and secure environment medicine.

The principle of equivalence has been instrumental in helping to define and contrast the care being delivered in secure settings with that of the care in the wider community, with the aim of mirroring of provision. Since 2006 and the move towards the commissioning of health services in prisons by the National Health Service, there has been a significant transformation in the quality and consistency of services being delivered to people in prison. By aiming to deliver healthcare services that are ‘equivalent’, and achieving equitable health outcomes, we are not only striving to improve the health of our secure and detained patients, we are also benefitting society as a whole.

The RCGP has recently launched Secure Environments Hub that features information about healthcare in secure environments and eLearning for clinicians and multi-disciplinary team related to the prison system. You can access the Hub here: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/view.php?id=561

The majority of people, including health care professionals (HCPs), have unconscious or implicit biases1. These can affect the way we interact with colleagues, staff and patients, and even influence our decision making in regards to diagnosis and management of conditions2.

Unconscious bias is the immediate judgement of something, or someone, based on our past experience, background and culture. It is instinctive rather than a rational thought process and occurs almost instantaneously on encountering someone new. This bias can then influence our thoughts, beliefs and behaviour towards that person.

When we first meet someone, we subconsciously categorise them based on, for example, their gender, age, skin colour, accent, profession, sexual orientation3. We then use preconceived ideas of their intrinsic characteristics and form an immediate opinion about the person. Most people have unconscious biases, no matter how strongly they consciously oppose discrimination or prejudice. We tend to feel positively about someone who is similar to us, and negatively about those we perceive as ‘different’. These assumptions then effect the relationship we have with that person, including how close we will stand to them, and how often we make eye contact2.

The term unconscious bias encompasses several types of bias such as gender bias, confirmation bias, age bias, and affinity bias, to name a few. These biases can affect everything from to which candidate we would offer a practice vacancy, to how we manage different patients with the same condition. It can be both positive and negative, as we may favour or disapprove of someone based on whether we feel they fit into ‘our group’ (namely, whether we feel they share similar characteristics to us).

Take a vacant salaried GP position as an example: You’re on the interview panel. The next applicant trained at the same medical school and enjoys the same hobbies as you. You immediately think ‘yes, this person is great’. The next applicant attended a rival medical school and has different hobbies; you’re not so sure about this applicant. This is an example of affinity bias. These opinions are formed without us even realising it and without taking into account the person’s qualifications or experience. Once that initial judgement is formed, our brain then begins to gather evidence to support our assessment. However, this ‘evidence’ is also biased (confirmation bias) as we look for anything that will uphold our initial decision and disregard items that refute it.

Unconscious bias is well recognised in the interviewing process, and many private companies have procedures in place to reduce the risk of this happening4. But how does this translate into the world of healthcare?

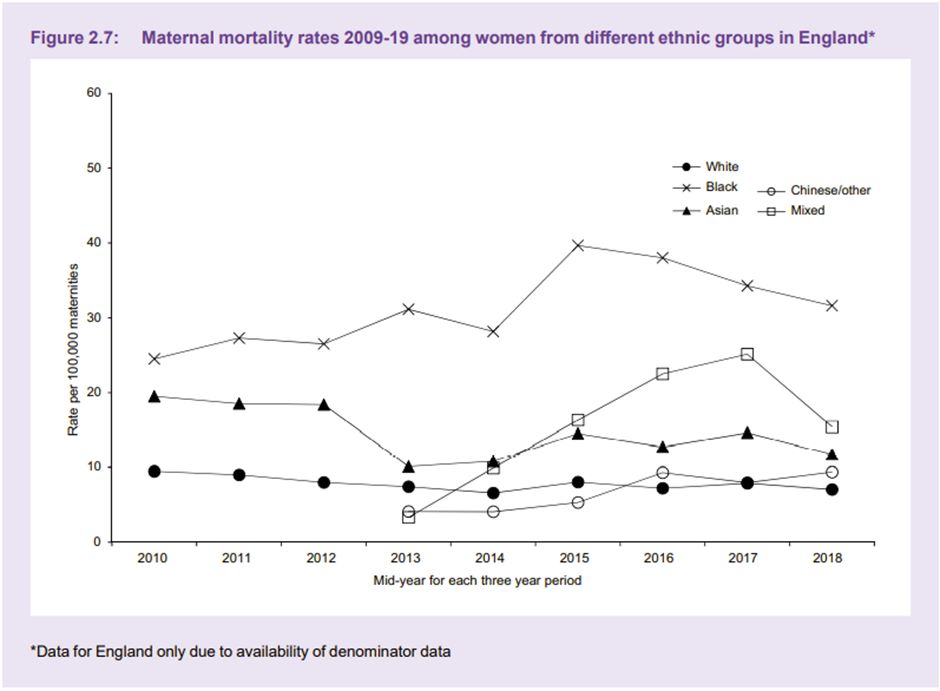

Unconscious bias may have a significant impact on medical school admissions, with one American study reporting a notable race bias5 by those on the selection panel. International medical graduates (IMGs) are up to thirteen times more likely to be referred to the GMC than UK graduates6, which is thought to be due, at least in part, to unconscious bias. We commonly hear of female doctors being called nurse whilst male nurses or medical students are called doctor and are often talked to in preference to their senior female colleague.Not only does unconscious bias affect us and our colleagues, but it also has a crucial and concerning impact on our patients. In 2021 Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risks through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK (MBRRACE-UK) released a report7 that showed black women were four times more likely to die in pregnancy than white women. Whilst socioeconomic factors and medical reasons were thought to contribute to the outcomes, this only accounted for a small proportion of women. Black women report not being listened to or empathised with as much as their white counterparts8.

Graph from MMBRACE-UK 'Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19'. Used with permission from MMBRACE-UK.

Several studies have shown that there is racial bias in regards to pain management, with black people frequently denied analgesia that their white counterparts are readily offered. Research by Hoffman et al (2016) reported that the false belief of biological differences between white and black people contributing to pain thresholds, are held by the general population, and more worryingly by medical students and qualified doctors9. This not only impacts women in labour, but all situations where adequate pain relief is important.

The Midlands Leadership Academy has developed an Unconscious Bias Toolkit10 which suggests several ways in which we can challenge our own unconscious biases. The toolkit advises us to consider:

- What am I thinking?

- Why am I thinking it?

- Is there a past experience that is impacting my current decision?

- Is the past experience applicable now or is it based on a preference or bias?

Furthermore, the Royal Society4 advise that we should slow down when making decisions, reconsider reasons for decisions, question cultural stereotypes and monitor each other for unconscious bias. The Royal College of Surgeons have published a document on reducing unconscious bias11 in which they suggest using Thiederman’s Seven Steps for defeating bias in the workplace.

|

1. Become mindful of your biases 2. Put your biases through triage 3. Identify the secondary gains of your biases 4. Dissect your biases 5. Identify common kinship groups 6. Shove your biases aside 7. Fake it till you make it (what we say can become what we believe) |

Medical education - whether undergraduate or postgraduate - has a responsibility to promote curricula in a non-biased way. There has recently been a push to decolonise medical education and incorporate cultural safety12: Decolonising medical education involves challenging beliefs and introducing ‘new normals’ such as representing signs and symptoms of illnesses in different skin tones; or promoting issues faced by discriminated groups, for example, including violence against women and racism in curricula13. Cultural safety is a concept developed by Māori Nurse Educator Irihapeti Merenia Ramsden, who recognised the health inequalities between indigenous and non-indigenous people in New Zealand. Cultural safety is to understand that health inequality is based on historical prejudice, and using lived experiences of those who have experienced discrimination ensures that differences in culture are respected throughout healthcare. If health care professionals and students understand how conditions may present in different ethnicities and genders, really listen to patients experiences and concerns regardless of their skin colour or own beliefs, and learn to challenge their unconscious bias, then hopefully we will develop a generation of healthcare professionals who can more fully appreciate and challenge health inequality in the UK.

The RCGP has recently launched an interactive eLearning module on Allyship, which includes information and suggested actions to promote anti-racism and bystander intervention. You can access the course here: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/allyship

References

- Schwarz, J., 1998. Roots of unconscious prejudice affect 90 to 95 percent of people, psychologists demonstrate at press conference, University of Washington, [online]. Available at: https://www.washington.edu/news/1998/09/29/roots-of-unconscious-prejudice-affect-90-to-95-percent-of-people-psychologists-demonstrate-at-press-conference/ [Accessed 06 April 2022]

- FitzGerald, C. and Hurst, S., 2017. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8.

- Rice, M., 2015. Unconscious bias and its effect on healthcare leadership. Healthcare Network, The Guardian. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2015/may/19/healthcare-leadership-best-practice-unconscious-bias. [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Frith, U., 2015. Understanding Unconscious Bias. The Royal Society. [online] Available at: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2015/unconscious-bias/?gclid=CjwKCAiA6seQBhAfEiwAvPqu18TssncdweUmNPHBiUb8o2UHBslILV8UOvM-fs7ePvbngXtmq6fdrRoC-PYQAvD_BwE. [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Capers, Q., 4th, Clinchot, D., McDougle, L., and Greenwald, A. G., 2017. Implicit Racial Bias in Medical School Admissions. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92(3) pp.365–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

- Rimmer A, 2017. Unconscious bias must be tackled to reduce worry about overseas trained doctors, says BAPIO. British Medical Journal, 357 :j1881 doi:10.1136/bmj.j1881.

- Knight, M., et al on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2017-19. [online] Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2021. Available at: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2021/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2021_-_FINAL_-_WEB_VERSION.pdf [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Brathwaite, C., 2018. Black Mothers Are Disproportionately More Likely To Die In Childbirth - We Need To Address The Race Gap In Motherhood. Huffington Post [online] Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/race-motherhood-black-mothers-dying-childbirth_uk_5c078da3e4b0a6e4ebd9d5ec [Accessed 04 April 2022].

- Hoffman, K.M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J.R., and Oliver, M.N., 2016. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), pp.4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.

- Masuwa, P. and Sharma, M. Unconscious bias toolkit. NHS Midlands Leadership Academy. [online] Available at: https://midlands.leadershipacademy.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/12/Unconscious-bias-toolkit-final-version.pdf.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2016. Avoiding Unconscious Bias: A guide for surgeons. [online] London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England (Published 2016) Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/rcs-publications/docs/avoiding-unconscious-bias/ [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Wong, S.H.M., Gishen, F. and Lokugamage, A.U., 2021. ‘Decolonising the Medical Curriculum‘: Humanising medicine through epistemic pluralism, cultural safety and critical consciousness. London Review of Education, 19(1). DOI: 10.14324/LRE.19.1.16.

- Lokugamage, A.U., Ahillan, T. and Pathberiya, S.D.C., 2020. Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics 46(4), pp.265-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866.

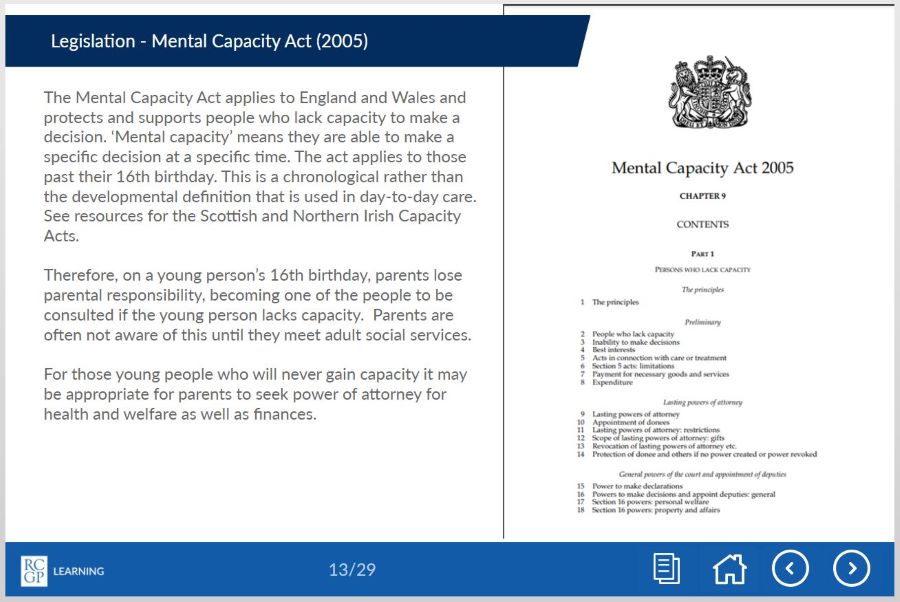

Children with life-limiting conditions face significant challenges when they transition from paediatric to adult care. The transition involves many changes: the young person will transfer to adult specialities, to adult social care, and will experience changes in educational provision and legal changes involving parental responsibility for medical decision making.

The transition has been described as a ‘cliff-edge’ event, during which children and their families face significant stress, challenges, and unmet needs. When general practice is already aware of such a patient within their practice, a good service is already provided in many cases, but often young people with these conditions are not always visible, as the majority of their care is provided by paediatrics. Many of these young patients who thus far have had long term continuity of care from their paediatricians feel nervous or have little confidence in general practice and their ability to meet their complex needs. In some cases this can lead to ‘fire-fighting’, where general practice has to respond to crisis calls from young people (or their carers) with whom they may have had limited contact.

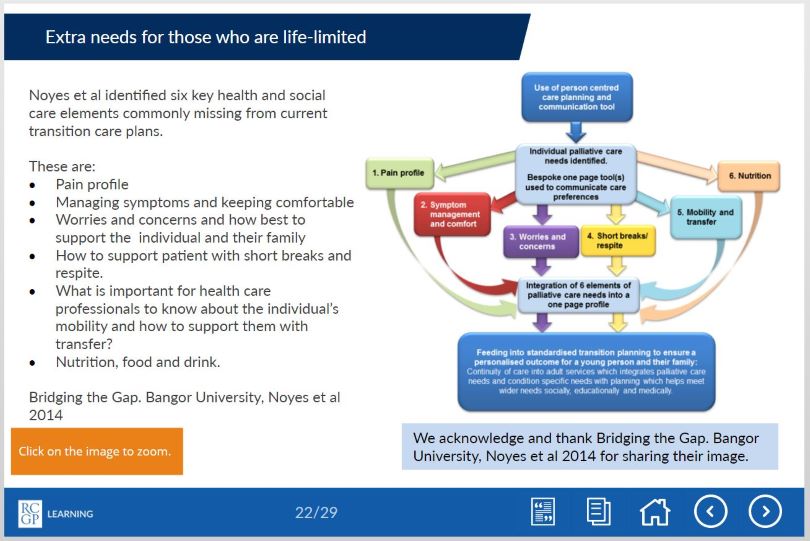

Recently, a small team at the RCGP – together with their colleagues from ‘Together for Short Lives’, produced an eLearning course on how the whole primary care team can contribute towards a good health transition from paediatric to adult care. These modules are for all primary care clinicians who want to provide excellent care for a young person with a chronic and/or life-limiting condition who is transitioning from paediatric to adult care. The modules are based on the insights generated by a pilot project which involved a steering group inclusive of general practice, palliative care, paediatricians, academics, and ‘Together for Short Lives’. Written by Dr Mike Miller, a paediatric palliative consultant with first hand experience of the pitfalls during transition and Dr Peter Lindsay, a GP with a special interest in paediatrics, the course combines the latest academic insights on health transition and the experiences of the authors and the steering group team.

During the pilot project, we recognised that there is overlap between young people with chronic and/or life-limiting conditions and young people with learning disabilities, and although the groups are distinct, there are similarities in their transition process. In many areas, local transition services for young people with complex needs are evolving rapidly: Leeds have developed an evolving transition network, and so far involves ongoing collaborations between education, the local children's hospice, social care, mental health services and learning disability leads.

As part of the pilot project, we performed initial searches within our practices for patients within these categories, and are now trying to develop processes to support transition. The pilot project highlighted the positive impact we can have in supporting the young person and family at a challenging and stressful time, and how we can improve health and social outcomes. As well as the routine care offered, general practice is uniquely placed to offer continuity of care through the transition period, early preparation for the transition to adult service, social prescribing and the help of the whole primary care team. Primary care is also perfectly placed to address health needs that often go under-recognised in this group, such as sexual health and contraception. If we can develop mechanisms to reliably identify these patients, then young people with chronic and/or limiting conditions will benefit from all that primary care can offer.

The eLearning modules firstly outline the challenges facing young people and their families during the transition period, from the perspective of a paediatric palliative care consultant who has devoted much of his career to improving the experience of young people and their families at transition. Secondly, poorly understood areas are tackled, such as the legal framework underpinning mental capacity at transition, and the practical implications of this for the young person and family. The second module presents practical approaches and best practice to support this area in a GP setting, in the current challenging and busy context of general practice. Please see below for some tasters from the eLearning modules.

Please also see the Developing Positive Transitions for Primary Care resources section, which signposts to further key information.

If you would like to learn more please see our eLearning modules and further learning resources:

'Better transitions: improving young people’s transfer from paediatric to adult services' eLearning course: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/bettertransitions

'Developing Positive Transitions for Primary Care' resources page: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/info.php?id=329

No-one expects their child to die before them – it isn’t the natural order of things.

From miscarriages to stillbirths and from perinatal deaths to deaths in childhood, the death of a child is a unique type of loss.

Pregnancy loss is the most common form of child loss. It is currently estimated that one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage1 so it is something many parents will experience. Even though they may have never been able to get to know their child, they will still feel a huge loss. They grieve the potential to get to know that child and the life they would have had. Many parents will also feel a sense of guilt following a miscarriage so it is important to look out for any hint of this and to reassure the parent that this was not their fault.

When a parent loses a child of any age, in that split second, their world is changed forever. They lose not only their child, but also many of the social networks linked to their child. They lose the potential to see that child grow up and if the child was their only child, their identity as a parent and the chance to become a grandparent. They lose not only the present but also the future. The loss of a child for this reason is very different to other types of grief.

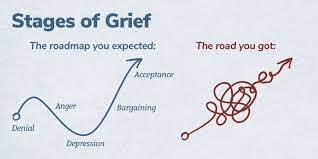

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

Traditionally, grief has been described in a series of stages: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Current thinking has now moved towards the ‘grieving process’ as a more accurate model. Whilst grieving, it is possible to move forwards and backwards between the phases over time. Some individuals skip phases and others may spend a long time at one particular stage. Certain anniversaries or triggers may cause the grieving person to move between phases fluidly.

In 2007, Harper et al showed that in the 15 years after losing a child or having a stillbirth, bereaved mothers were 2-4 times more likely to die than non-bereaved mothers and that the excess risk persists for 35 years after the bereavement, though the magnitude of the risk drops with time. The increased risk persists for three years for fathers, though clearly they have an increased risk of being widowed for much longer. The reasons for this phenomenon are not clear, but could involve immunosuppression due to severe stress, maladaptive coping strategies such as alcohol misuse, pre-existing poor health which may have contributed to the child bereavement, mental ill-health following bereavement, or bereaved parents presenting later with their own physical health problems. Further research into this area would be useful. The relevance to general practice is probably that we should be aware of this risk and make particular use of the GP ‘spidey sense’ when dealing with this group of patients. Never ignore your gut feeling as a GP – it has been shown to be reliable3.

I am writing this blog from personal experience, after losing my four-year-old daughter Grace to cancer in 2014. My personal experiences have helped me to support many other families in similar situations and in 2018 I wrote an eLearning course for the RCGP, designed to provide GPs with the tools to support patients who have experienced a loss during pregnancy, or the death of an infant or child. Each family needs something different, but the overwhelming message is that having someone simply able to be there for them as a point of contact, it can make a big difference.

When a family loses a child, it also has a significant impact on their siblings. Life for their surviving siblings never returns to normal so it is important to remember that their bereavement will affect many aspects of their life and behaviour.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

“I feel like there is a piece of me missing. My friends get to play with their brothers and sisters. All I can do is look at a photo or visit his grave. It just isn’t fair. I feel on my own, and my friends don’t understand.” A bereaved sibling, aged 8.

Often, a few simple measures taken by a practice can make a sizable difference to help families realise that they are not alone. When the practice has been informed of a child death, it is important to contact the family, by phone if possible. This need only be brief, but families do appreciate this and remember this contact down the line.

Families should be provided with a named GP, and alerts placed on the notes of both parents and all siblings so practice staff and professionals can be aware of the history without the family needing to repeat themselves each time.

If possible, enable bereaved parents and siblings to make appointments at minimal notice for a limited time. The death of a child can plunge a family into chaos meaning things are easily forgotten or they may need to be seen quickly to help with acute emotional situations.

Ensure that all professionals are notified. Check that electronic alerts inviting the deceased child for immunisations, reviews or other routine care have been turned off. It is also useful to familiarise yourself with the services and support that are available in your local area to signpost families to as required.

General Practice is extremely busy at the moment, but these simple measures are relatively time efficient and can make a real difference to these families.

References

1 Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O'Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med, 1988; 319(4): 189-94.

2 Harper M, O'Connor RC, O'Carroll RE. Increased mortality in parents bereaved in the first year of their child's life. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2011; 1(3): 306-9.

3 Friedemann Smith C, Drew S, Ziebland S et al. Understanding the role of GPs’ gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. British Journal of General Practice 2020; 70 (698): e612-e621.

'Stages of Grief' image used with permission from WPSU's Speaking Grief project.

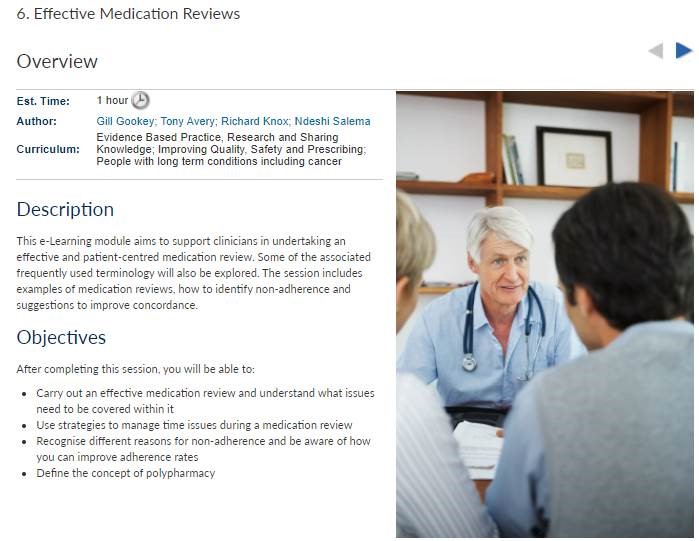

An NIHR GM PSTRC (NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre) funded free e-learning course which has been accessed by 7000 prescribers since 2014 has undergone an evaluation and been re-launched with the addition of new content.

Dr Richard Knox from the University of Nottingham is one of the researchers who has worked on the e-learning course, Prescribing in General Practice. He talks about the impact of the course and the new updates here:

Prescribing in General Practice is an e-learning course, hosted on the Royal College of General Practitioners’ (RCGP’s) e-learning platform. It’s a case-based approach designed by prescribers so there’s a focus on real life examples. It was launched in 2014 and has recently undergone revisions from people who use it to ensure all the real-life examples that are used meet current guidelines. The course was also evaluated by researchers at the GM PSTRC in a new paper, which has been published in the journal Education for Primary Care.

To help assess the course’s success, in the paper, researchers used the results of a questionnaire completed by those who finished the e-learning modules. According to this the course had a positive impact on knowledge, skills and attitudes. More than 98% of 750 survey responders said the course had been a useful part of their continuing professional development.

Those who responded also wrote additional feedback and some examples are below:

“This module comprehensively covered contemporary prescribing issues particularly with respect to safety. It was grounded in everyday practice and informed by real life examples of prescribing errors and how they may occur and how to mitigate against them at an individual and at a systems level.”

“Usefully it was from the RCGP so the majority of medicines and cases presented were similar to what I would encounter on a daily basis in work. I feel from completing this module my safety and efficiency in prescribing will improve.”

“This course is going to change/improve many aspects of my prescribing practice. I would definitely spend more time on writing clear instructions for patient.”

The course was initially developed to facilitate safer prescribing among GPs. However, funding from the GM PSTRC has enabled the course to be free-to-use for all prescribers, regardless of professional background. This has increased the impact of the course which improves the safety of prescribing more widely.

The original idea for the e-learning materials came as a direct result of findings from the General Medical Council’s PRACtICe study. This was a large study of prescribing errors in UK general practice, which revealed that about one in twenty prescriptions from primary care contains an error. The PRACtICe study included a root cause analysis that helped establish a set of recommended strategies that may improve prescribing. The need to invest further in education and training was identified by all GPs, whatever their stage or experience of prescribing. A series of focus groups made up of GP trainers, GPs in training, pharmacists and members of the public also confirmed support for further training to be made available. The value of e-learning was championed – with stakeholders requesting a strong case-based approach to help inform real-world practice.

The e-learning includes five distinct lessons, each taking about thirty minutes to complete:

- Lesson one – Appropriate drug selection

- Lesson two – Avoiding prescribing errors

- Lesson three – Choosing the right drug

- Lesson four – Right dose instructions

- Lesson five – Effective medication reviews

Due to the updates the course now includes specific sections on topics such as prescribing multiple medications for the same person at the same time (polypharmacy) and the use of the Seven Step medication review process.

Please note, this course is now RCGP Members' benefit. Non-members have an option to purchase the course. You can access the Prescribing in General Practice course here.

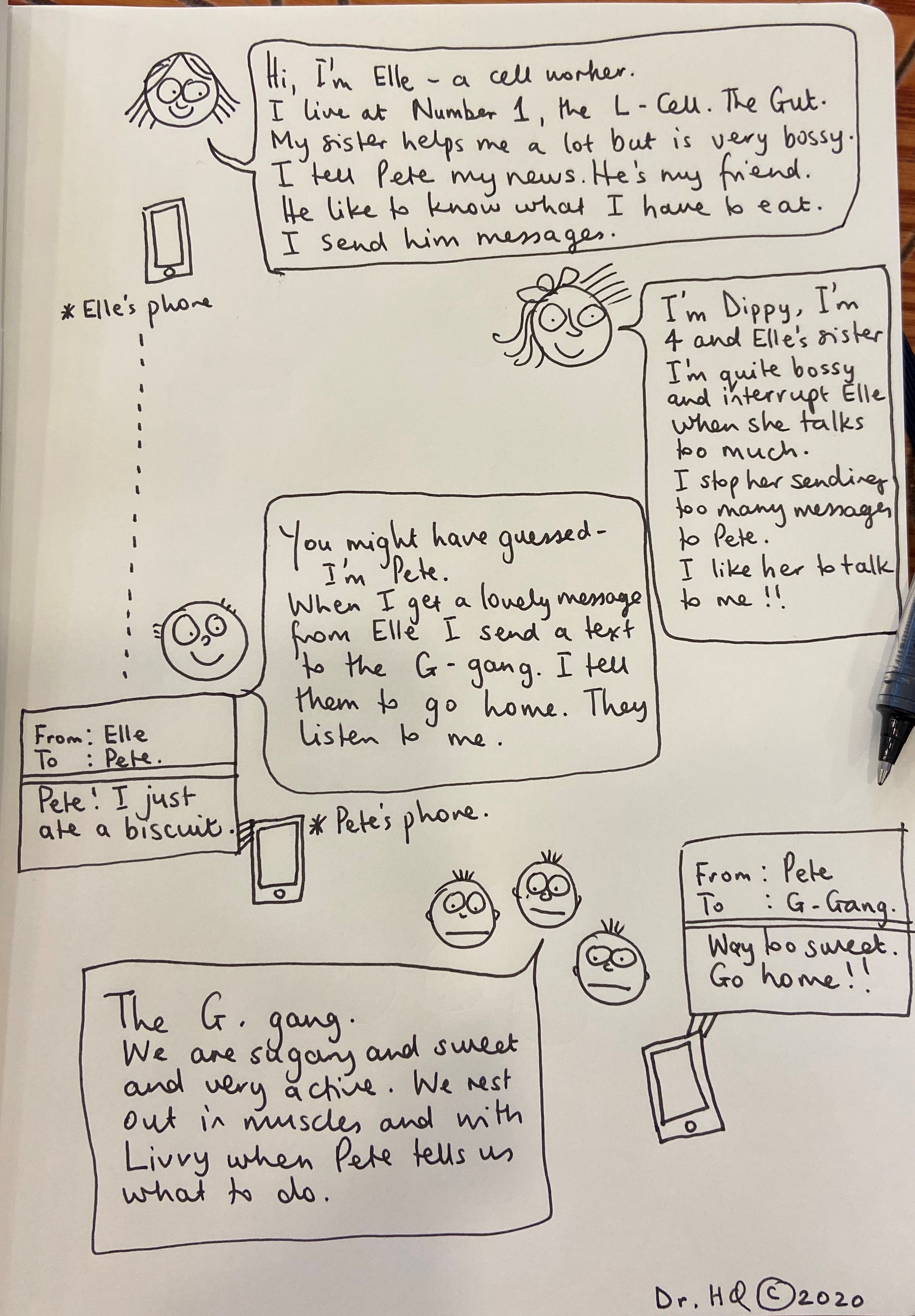

“Medicine is an art whose magic and creative ability have long been recognised as residing in the interpersonal aspects of the patient-physician relationship1”.

Art is part of medical training from early on - lectures in medical school use images, cartoons, animations, and demonstration models. In our hospital jobs we all used drawings, lung fields with crosses, or a hexagon abdomen with a large liver on it were all used in the days of paper notes. However when asked to draw, medical students often recoil and claim that they are ‘not creative’ and cannot draw2.

We are trained in communication skills to gather information in order to facilitate accurate diagnosis, counsel and give therapeutic instructions whilst establishing caring relationships with patients3. Patients gather information from many different visual sources in the GP surgery, so using drawings is a natural next step, yet one that is rarely discussed.

We already use visual imagery in the consultation - as GPs we might point to anatomical posters in our rooms, use drawings for minor surgery consent, or the “clock test” in dementia screening. Encouraging people to see drawing as a form of learning can help them to present information more efficiently within the consultation4.

We also all use metaphor and analogy frequently - as Anatole Broyard describes, metaphors may be as necessary to illness as they are to literature and are a relief from medical terminology5. Metaphors bridge the communication gap between healthcare professionals and patients, examples including the following:

“My tongue feels weird, like licking a battery.” (Oral thrush)

“Doctor, you know when you put your hand in a bag of rice – that nice sort of tingly feeling – I get that in my head in a sort of shock.” (SSRI discontinuation syndrome)

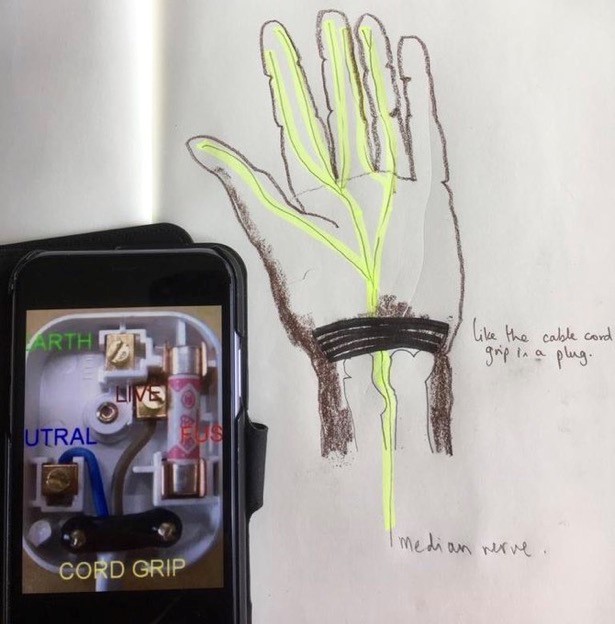

Clinicians can use visual metaphors; drawing a plug to describe the wrist retinaculum (Image 1) can increase understanding of the pathophysiology of carpal tunnel symptoms and be a simple start from which patients can improve their understanding.

Clinicians can use visual metaphors; drawing a plug to describe the wrist retinaculum (Image 1) can increase understanding of the pathophysiology of carpal tunnel symptoms and be a simple start from which patients can improve their understanding.

While anecdotal evidence for the benefits of drawing in the consultation is plentiful, research is limited: A team at Edinburgh university were the first to document the use of drawing amongst 100 surgeons, 92% of whom valued drawing in surgical practice2. Similarly, the vast majority of patients valued drawing in moderate or complex surgery consent explanations3. There is plenty of evidence for the neurological and cognitive benefits of using images in undergraduate and postgraduate pedagogy4, alongside the cognitive processing of learning5.

Before I studied medicine I attended the Glasgow School Of Art, reading Visual Communication. I was taught to consider what it was I wanted to say, and then work out how best to communicate it visually. This meant considering which material to use and to capture the spirit of the subject I was drawing using appropriately descriptive markings. This trained me to describe the essence of a concept or object and its function or position in the world. These principles can add value to a consultation as drawing supplements or contextualises the words we use. It can improve a patient’s understanding of physiology, pathology and pharmacology and reduce health anxiety; there is evidence that patient drawings can predict health outcomes and provide doctors with more insight into the patient experience6. Cartoons can be particularly helpful to explain pharmacology, particularly for those with limited literacy (Image 2). Colour is important – the red of an inflamed tympanic membrane, or a different colour to demonstrate a middle ear effusion. Just a few different pens can improve understanding.

My patients often ask to keep the drawings that I do (sometimes with the patient’s help) in a consultation as it represents their understanding of what was said. I see drawing as an adjunct in communication and possibly as a way to reduce complaints that can arise when patients feel that they have not been heard.

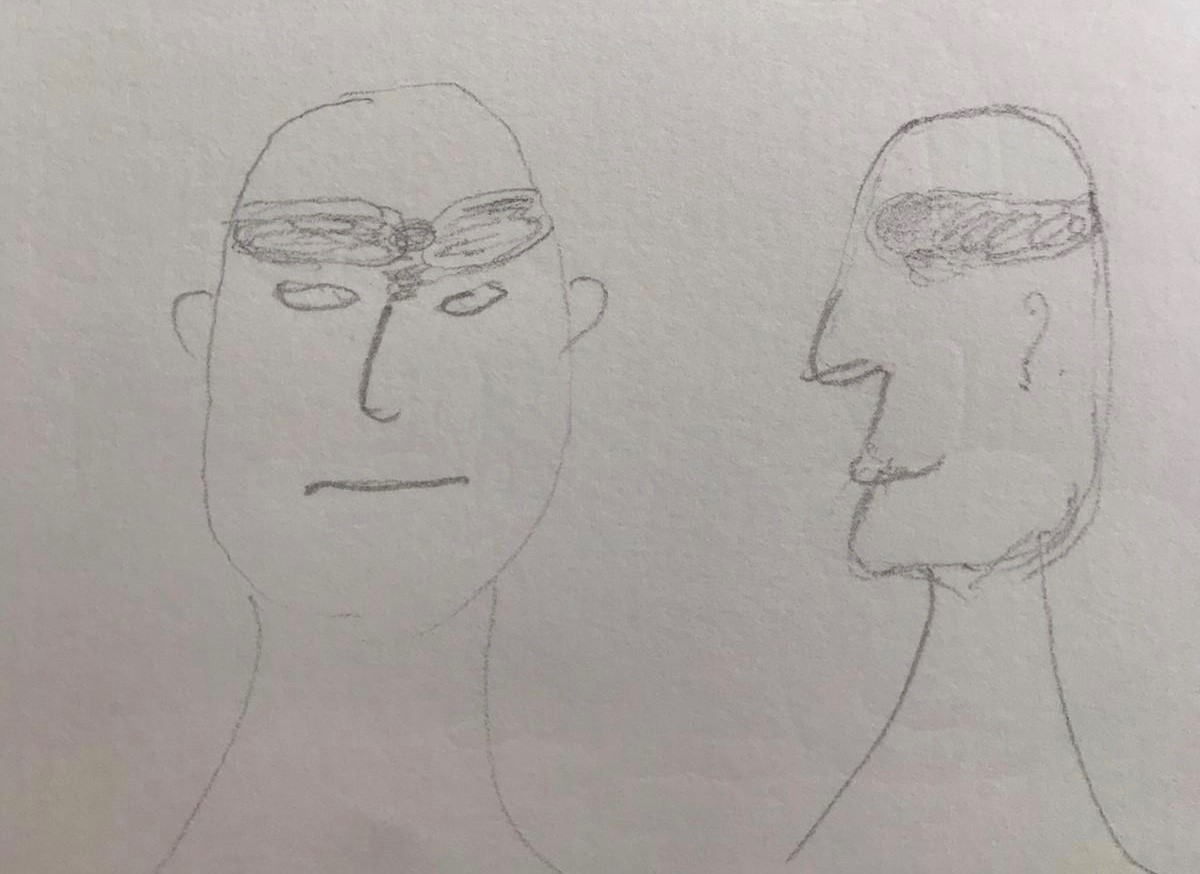

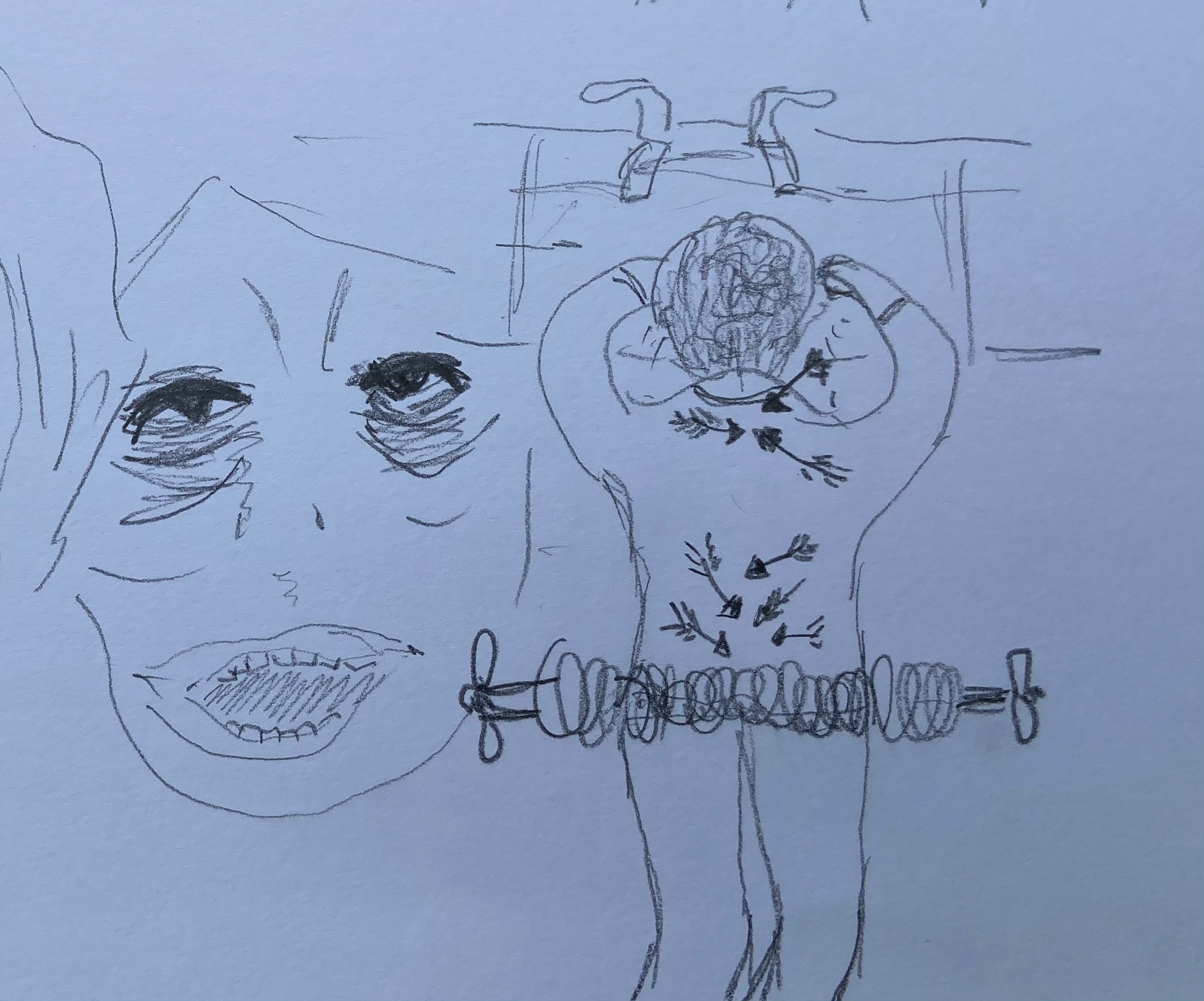

The use of images is not one-way as patients may add their own drawing, or bring pictures on their mobile device6. The following drawings (with patient permission) show personal representation of the pain experience in cluster headache (Image 3) and in these descriptive sketches (Image 4) the pain of end stage osteoarthritis with spondylolisthesis. Reference to the feeling of dragging and vice-like pain can be seen. I am not alone – there are other professionals using imagery in medicine.

Professor Gabrielle Finn fosters a network of artists, scientists, educators and health professionals interested in alternative methods of displaying by painting anatomical structures directly onto the body. She has kindly given permission for an image to be used here (Image 5). Her work crosses specialties and encourages innovative alternative approaches to learning.

The team around Professor Paul Rea, Professor of Digital and Anatomical Education at the University of Glasgow, created an animation explaining hypertension using clay models which simply describe concepts which are difficult to describe verbally.

Professor Alice Roberts, Professor of the Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham, uploads anatomical videos of embryological folding, and musculoskeletal anatomy, sometimes with the help of Jelly Babies.

In summary, at times there is a need in the doctor-patient consultation to change or extend the communication style. We can let our patients take over the pen to illustrate their concerns or symptoms. Good communication within the GP consultation and the use of alternative techniques to describe issues are valuable tools : sometime words fall short.

This blog was written by Dr Holly Quinton, GP and Illustrator. All images in this blog were provided by Holly with patients' consent. You can read more about Holly and visual consultations in the following BJGP article: How I use drawing and creative processes within the GP consultation.

References:

1Hall JA, Roter DL, Rand CSJ Health Soc Behav. 1981 Mar; 22(1):18-30

2Keenan I, Hutchinson J, Bell K, 2017, 'Twelve tips for implementing artistic learning approaches in anatomy education', MedEdPublish, 6, [2], 44, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000106

3 Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R, Buffone N, Lofton S, Wallace M, Goode L, Langdon L; Participants in the American Academy on Physician and Patient's Conference on Education and Evaluation of Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004 Jun;79(6):495-507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. PMID: 15165967.

4 Keenan I, Hutchinson J, Bell K, 2017, 'Twelve tips for implementing artistic learning approaches in anatomy education', MedEdPublish, 6, [2], 44, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000106

5 C Kotei: Metaphors in Medicine Synapsis Journal Oct 2017

6 Daeboudt, Broadbent, Berger & Kaptein, Lupus, 20,290-289